Where there’s a Will

The history of pewter in America is representative of the wider colonial experience. In the late 17th century, Britain passed a series of laws called the Navigation Acts governing colonial trade. The Acts limited the colonies to trading with Britain, and increased Britain’s advantage by imposing further restrictions and duties on colonial trade. In this system of political economy, later labeled Mercantilism by Adam Smith, government regulation of the economy was for the purpose of building state power and wealth. Colonies existed for the economic benefit of the imperial power.

Pewter is an alloy of mostly tin, which Britain mined in Cornwall. The colonies lacked a source of tin, but could not purchase tin from Britain. They could only purchase finished pewter merchandise and pewter ingots, which because of tariffs cost as much as the finished products. Britain had a thriving pewter industry to protect, governed by a London guild set up in 1473, and selling to the colonies while impeding the development of local manufacturing ensured a favorable balance of trade.

Pewter was in great demand in America. Annual pewter imports from Britain had grown to more than 300 tons by 1760. Connecticut pewterer Thomas Danforth Boardman wrote “From the Landing of the Pilgrims to the Peace of the revolution Most all, if not all, used pewter plaits and platters, cups, and porringers imported from London & made up of the old worn out,” (Montgomery). Pewterers in the colonies resourcefully purchased worn out pewter from households, which they melted down and reworked. Pewter is a soft metal and most pieces had a useful life of about ten years before becoming misshapen. American pewterers exchanged of reworked merchandise for customers’ old worn pewter. Because of the necessity of melting and reworking, American pewter today is more valuable than British pewter. There is simply less of it.

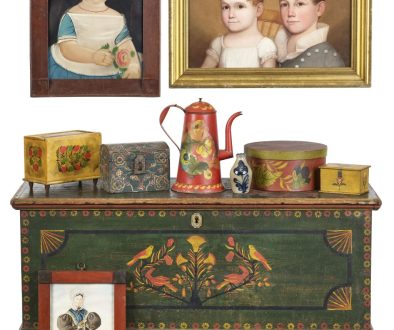

A colonial pewterer would assay old pewterware into different grades to be melted down and then poured into his assortment of molds. The molded pieces were fitted and soldered together to create coffeepots, sugar bowls, creamers, etc. Since a pewterer only had so many molds, the shapes were used interchangeably for different pieces. The same mold could be used for the lid for a teapot or the base of a chalice. A flagon could be assembled from as many as fourteen parts, all of which had to be useful in creating other wares.

William Will brings us to the conclusion of our study of American pewter and mercantilism. His story has been told often, but is a good one, and neatly illuminates the result of England’s trade policies. William Will (Philadelphia 1742-1798) is regarded as the finest American pewterer of the 18th c. “His ability to make new designs by using interchangeable parts cast from existing molds was unequaled by any other American pewterer,” (Herr). A German immigrant from a family of pewterers, William practiced in Philadelphia, and was so successful that he achieved status as a leading citizen. “No other has left a more impressive evidence of ability, and few approached the craftsmanship which his pewter displays. Gifted beyond most of his fellows, he unselfishly subordinated his business to a life of service to his community and demonstrated that he was not only a superior craftsman, but also a splendid soldier, a capable statesman, and an executive of unusual ability,” (Laughlin). William Will contributed to ridding the American colonies of the effects of British mercantilism. Forming an infantry company in 1776, he served as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Philadelphia Militia’s 3rd Battalion in 1777 and 1780. Much was asked of him, as in 1777 he was also appointed one of six Commissioners for the seizure of traitor’s property, in 1779 named storekeeper in Lancaster for the Continental Army, in 1781 was elected sheriff of Philadelphia, and in 1785 was elected, along with Robert Morris, to the General Assembly in the newly independent United States of America.

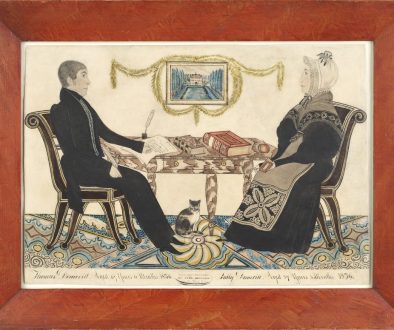

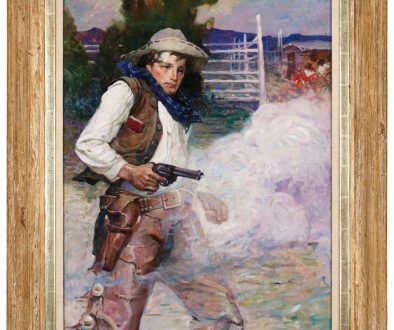

Pook & Pook invites you to join us for our September 25-27th Americana & International sale, which will feature important American pewter, and many pieces marked by William Will himself.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Bibliography

Charles Montgomery, A History of American Pewter, Winterthur, 1973.

Donald Herr, Pewter in Pennsylvania German Churches, Pennsylvania German Society, 1995.

Ledlie Laughlin, Pewter in America, Houghton Mifflin, 1940.