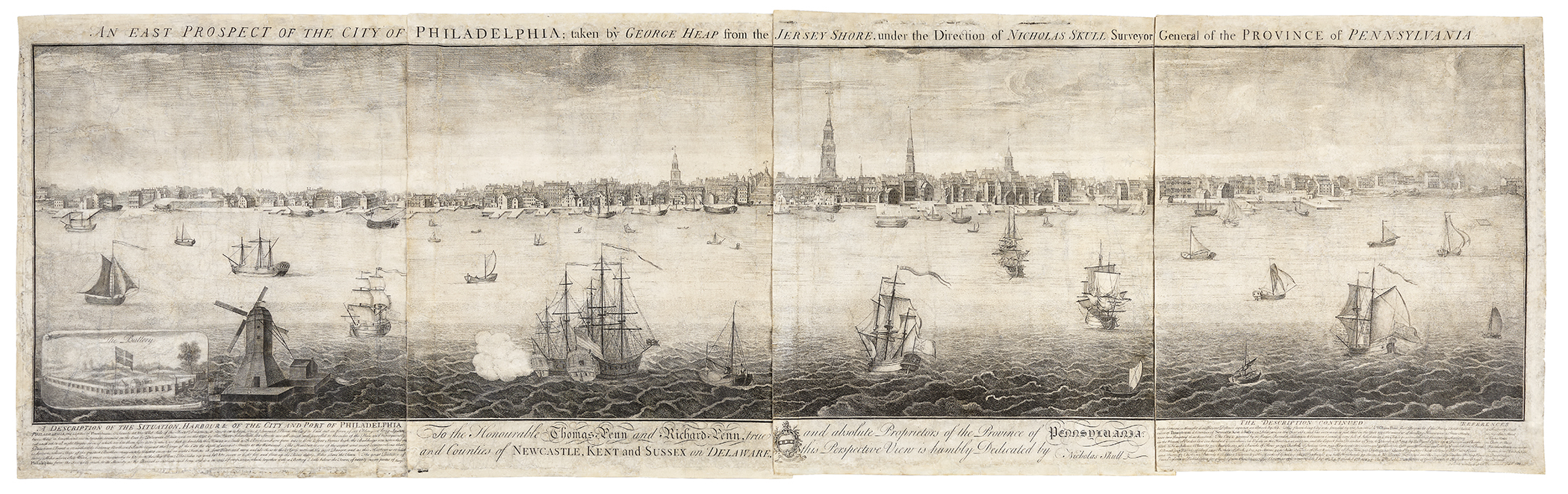

An East Prospect of the City of Philadelphia

The year was 1750. Thomas Penn needed to raise some cash. In spite of his father William Penn founding the colony of Pennsylvania in 1681, the family was deeply in debt. They had never seen income from the colony, and needed to realize a return on it. Following the deaths of his father, William Penn, and brother John, Thomas was chief proprietor of Pennsylvania. He had already spent almost a decade in the colony, collecting rents and engineering the Walking Purchase of land from the Lenape. Thomas had returned to England, but retained control over Pennsylvania affairs.

Penn commissioned his agent, Richard Peters, to find an artist to create an engraved view of Philadelphia, along the lines of the William Burgis views of Boston and New York. He wanted it taken from the Jersey Shore, opposite Market Street, to show its prosperous harbor, the most prominent port on the Atlantic. Penn wanted to send copies to all of his friends and influential contacts to advertise how the city had grown, in order to drive commerce and immigration.

Local artist George Heap (1714-1752), of whom little is known, had already contributed a view of the State House to a joint project with surveyor Nicholas Scull, the 1752 A Map of Philadelphia, and Parts Adjacent. The older Scull may have been an uncle, for after Heap’s father died, he followed Scull into surveying. He seems to have prospered. He married, purchased land, and was elected coroner in 1749. As artist after artist failed to create an acceptable picture of the city, Heap decided to make his own.

To solve the problem of distance and flatness that had defeated previous artists, Heap strategically omitted some details and brought the city closer in view. He then laid out Philadelphia’s immaculately gridded streets from present-day South to Vine Street, just under a mile of waterfront, on a colossal seven feet of paper. Just how much help he received from Scull in the design is unknown. The enlarged view and lengthy ground allowed Heap to include an incredible amount of detail, capturing the vitality of the city. He embellished the drawing with the Penn coat of arms, a dedication, and a reference key with landmarks such as Christchurch, the Statehouse, the Academy, and Courthouse. The resulting work went beyond the previous colonial city perspectives of Burgis. Heap’s creation stands as the largest and most artistically important view of any American city of the period.

Peters offered to buy the drawing for Penn, but Heap “refused to sell save for an exorbitant price.” (Wainwright p.19) Ambitiously, Heap intended to have it engraved and printed himself. He finished the work in September 1752 and advertised for subscribers, whose deposits would finance the printing. Due to its immense size, London was the only location equipped to handle the engraving. Three short days into his voyage to London, Heap unexpectedly died. His sea chest, containing the drawing, and his body were returned to Philadelphia.

Former partner Scull purchased the drawing from Heap’s widow. Nicholas Scull (1687-1761) was a prominent Philadelphia figure, the middle generation of a dynastic line of surveyors. He served as the first deputy surveyor of Philadelphia in 1719, during which time he mapped the land between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. In 1741 he helped survey the land acquired in the Walking Purchase and was valued due to his ability to speak Lenni-Lenape. From 1727, he was a founding member of Benjamin Franklin’s Junto Club, a group of twelve friends from different professions who met to discuss philosophical and political issues. Married to Abigail Heap since 1708, he was probably an uncle to the younger George Heap.

The original drawing having become soiled, Scull paid artist John Winter to make a copy, which he then shipped to Thomas Penn in London in 1753. Penn contracted engraver Gerard Vandergucht to produce the enormous engraving, requiring four copper plates, which combined to form a picture eighty-two inches long. In June 1754, 500 first state copies were printed, 450 of which were shipped to Philadelphia and 50 for Penn in England. Penn presented one to the King “who is pleased with it, and has hung it in his own private apartment.” (Wainwright, p. 21)

An East Prospect of the City of Philadelphia: Taken by George Heap from the Jersey Shore, under the Direction of Nicholas Skull Surveyor General of the Province of Pennsylvania, stands as the largest and most artistically important view of any American city of the period. Nicholas B. Wainwright commends it as “The most distinguished of all prints of the city of Philadelphia in terms of age, rarity, and historic importance.” Due to its size and composition of four folio pages, there are very few known copies remaining. Only eight are counted in public institutions. The energy of the city perspective is remarkable, its river teeming with boats and its streets populated by citizens going about daily business. It is a portrayal of a city beginning a fifty-year reign as the “richest, busiest, and most cosmopolitan city of America,” (Drepperd, p. 42).

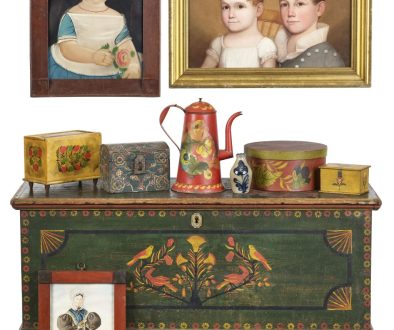

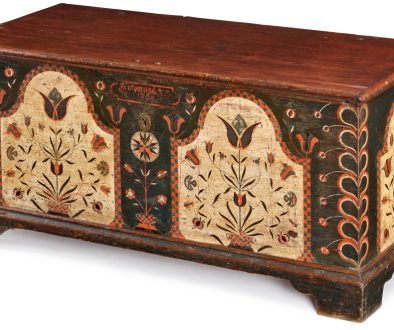

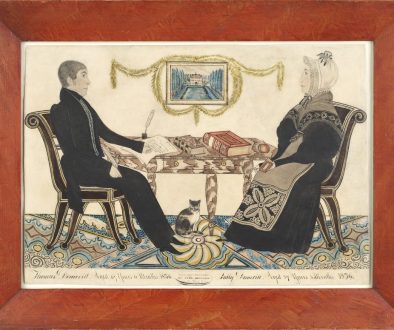

Join us at Pook & Pook for our January 16th & 17th Americana and International Sale to view this (Lot 544) and other historic treasures.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

References:

Brandis, Alex, Nicolas Scull II, American Revolutionary Geographies Online.

Snyder, Martin P., City of Independence, Views of Philadelphia before 1800, 1975, pp. 35-47.

Wainwright, Nicholas B. Scull and Heap’s East Prospect of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, January 1949, pp. 16-25.

Drepperd, Carl W., American Pioneer Arts and Artists, 1942, p. 42.