Don’t Take Candy from Strangers

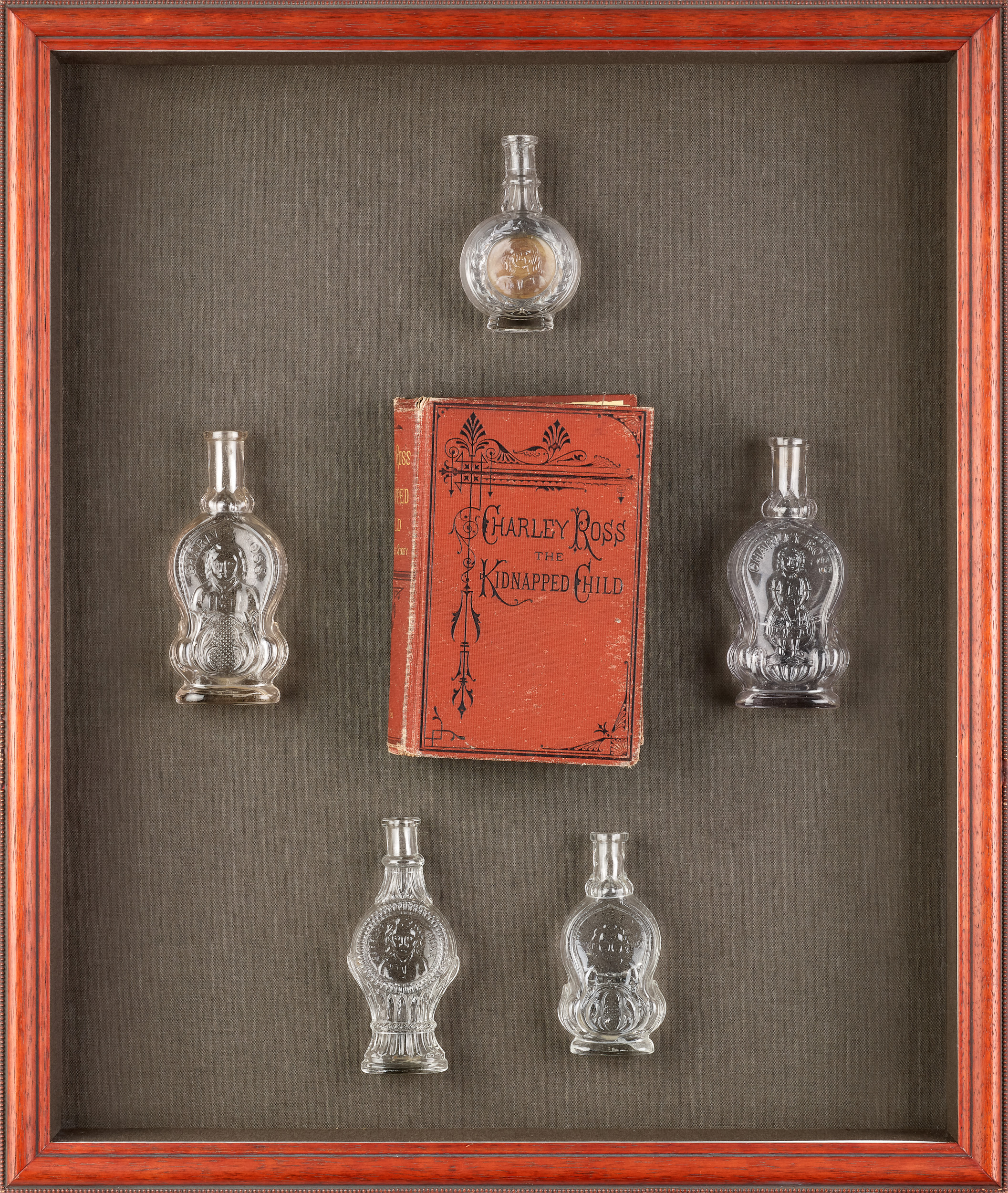

Two lots not to be missed are #248 and #317. They are a glass perfume bottle and a shadow box frame containing five bottles and a book, items easy enough to walk past without a second glance—but once their context is understood, they are impossible to forget.

In July 1st, 1874, in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia two brothers, ages four and five, were playing in their front yard when they were lured into a wagon by two men who had been seen giving them candy on several occasions. The older boy, Walter Ross, was found miles away outside a store. The younger boy, Charley Ross, was never seen again. Soon afterwards, their father Christian Ross received the first of many shocking ransom demands, $20,000 for the return of his son. Ross had lost a great deal of money in the stock market collapse of 1873 and did not have $20,000. He turned to the Philadelphia police department for help.

The organized police force had only been around for two decades before Charley was kidnapped. The police and the city had no idea what to do. The kidnapping of Charley Ross was the first recorded kidnapping for ransom in the United States. There were no procedures to follow. Kidnapping wasn’t even recognized as a crime, and many crimes were ignored, either because they were not yet recognized as crimes, or because the fledgling institution was still short of attaining the professionalism needed. Because of low pay, policemen were allowed to claim monetary rewards for solving old cases, and many police worked second jobs as thief catchers, compromising their integrity.

People had little faith in the ability of the police to catch the kidnappers. The New York newspapers were instantly critical of Philadelphia’s force. Once the Philadelphia newspapers expressed frustration over the lack of success, a city-wide effort began- which quickly became nationwide. Once the City posted a $20,000 reward for information leading to the capture of the kidnappers, everyone became a detective. People reported sightings of strangers with children, and searched gypsy camps and the countryside. Reports flooded in from all over the nation. Civilian search parties scoured the city. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote “Almost every man has been a detective in the case.” Charley’s disappearance became a cultural phenomenon. Sentimental songs were written imploring for his return. Leaflets and posters were put up everywhere, many paid for by the Ross family. Christian Ross also wrote a book, a personal narrative of the tragedy. Glass bottles were impressed with Charley’s image, like an earlier version of today’s milk carton children. The general population’s obsession lasted for decades, the nation riveted by a tale of true crime.

The City of Philadelphia, led by Mayor Stokely, who was himself directed by an unofficial committee of party advisors, advised Mr Ross not to pay the ransom, fearing it would lead to a kidnapping epidemic if the criminals could snatch a child and get paid $20,000. Their motives will never be fully known, but one major concern was the upcoming Centennial Exhibition of 1876, the first World’s Fair to be held in the United States, and the centennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia was spending hundreds of thousands of dollars preparing the city for a huge influx of visitors. If the kidnappers were successful, how would any family feel safe bringing children into the city? The Mayor and the committee advised Christian Ross not to give into the kidnapper’s demands. They helped the Ross family by responding to the ransom notes, always putting off the payment. More helpfully, the City ordered a search of every house, and changed the law to make kidnapping a crime and established sentencing for it. The City’s grandest gesture, the $20,000 reward, had unforeseen consequences.

While the New York papers were highly critical of the Philadelphia police force’s competence in the case, it was one of their own police who impeded its resolution. NYC Superintendent George Walling received a report from an officer who had immediately recognized the description of the kidnappers: William Mosher, a middle-aged river pirate and known criminal whose nose cartilage had been destroyed by syphilis, leaving him with a shortened, highly distinctive snout, and Joseph Douglas, a young career criminal with bright orange hair. They lived in Philadelphia but were frequently found in the Five Points neighborhood of New York City, organizing and committing crimes. Mosher’s wife was the sister of a former NYC police officer, William Westervelt. Once this connection was made by Superintendent Walling, he hired Westervelt to spy on his sister’s husband. Months passed with no new developments, other than a series of malign ransom letters and news speculation. Walling could at any time have arrested Mosher and Douglas, but he waited until he could get irrefutable evidence, and perhaps Charley himself, because then he could legally claim the $20,000 reward.

But Westervelt was a double agent, informing the kidnappers of the police department’s every more. The sinister ransom letters continued. Mosher and Douglas returned to river pirating, and were shot one night while robbing a home on Long Island. As he died, Douglas confessed to the kidnapping, and said that Mosher knew where Charley was, not knowing that Mosher was already dead.

Even though Westervelt was later imprisoned as an accomplice in the cover-up, Superintendent Walling escaped any blame. In her 2011 book on the subject “we is got him”, Carrie Hagen reasons that Charley had remained, except during the city-wide search, in Philadelphia the entire time, mingled in amongst the four or five children of the Mosher household. During this time, one of the Mosher children died of an illness. The dead child was likely Charley. Martha Mosher never confessed any involvement in the crime, but in interviews muddled her children’s ages and names, especially that of the deceased child.

The Ross family never stopped searching for Charley, and spent some $60,000 on the effort to recover him. Meaghan Good, founder of the largest online database of missing persons, named her creation The Charley Project in honor of him. Today, the database counts nearly 16,000 missing persons, and of Charley, Ms Good notes “He was basically the Lindbergh baby of the 1800s.” A cultural icon, the law was changed because of his abduction, the nation’s thoughts were focused on his return, helping to pull the populace together after the divisions of the Civil War, and we have the universal childhood admonition “Don’t take candy from strangers.”

by Cynthia Beech Lawrence