Pay Attention to the Man Behind the Curtain

Not every minor artist toils in obscurity. Relegated down the ranks of 19th century American painters by history, William Russell Smith was an eminent artist in his day. He is important because his paintings preserve images of a young nation, his diaries record a host of painters and historical figures, and his life story captures much of the 19th century American experience.

Born in the damp smoke of Glasgow’s Industrial Revolution, Russell suffered a bout of scarlet fever that was to leave him deaf in one ear and plagued by migraine headaches. His father, born in a castle to its hereditary caretakers, and his medical student mother, from a family of academics, were social reformers who left the climate of increasing unrest and violent repression for a brighter future in America. Prescient in more ways than one, they emigrated in 1819, just before the Radical War.

Three weeks of walking beside a Conestoga wagon pulled by six horses brought the family to their destination in western Pennsylvania. Their farm on the Conemaugh River was in wilderness. For seven year-old Russell, the experience was an education in the beauty and power of Nature, labor and the bare necessities of life, and in the frailty of life. A worker’s death from a rattlesnake bite left him with a lifelong aversion to snakes. His later journals mention killing many of them in his sketching rambles.

His family moved to Pittsburgh two years later so the children could attend school and his father, a whitesmith, established a cutlery business. Russell was often ill and wound up doing a lot of homeschooling. Early on, he knew that he wanted to be a painter. When his brothers launched an amateur theatrical group in art-starved Pittsburgh, Russell painted the scenery (and played the female roles). He also began to study painting with artist James R. Lambdin in exchange for aiding him in opening Pittsburgh’s first museum. Russell’s apprenticeship sounds not unlike training in a modern-day auction house; “he had little time to paint or give instruction and I gradually drifted into helping in the stuffing of birds and beasts, arranging minerals, antiquities and Indian costumes…and hanging the pictures, etc.”

Russell was rescued from the cultural backwater of Pittsburgh by Francis Wemyss, who brought him to the Walnut Street Theater in Philadelphia in 1835. Over the next several years, Russell Smith rose to prominence as a painter of theater curtains and backdrops. His circle of friends expanded to include theater luminaries and patrons, and his close friends included John Sartain and Rembrandt Peale. He painted and exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. In 1838 he married artist Mary Priscilla Wilson and started a family, prompting him to look for a place outside of the city where he could focus on landscape painting. To buy land, he sold his United Bank shares. Fifteen days later, the bank crashed. Russell’s money was safe, but his customers took a hit, and commissions slowed. To finance his landscape painting, he switched gears and travelled with state-sponsored geological expeditions in Virginia and Pennsylvania, creating illustrations for scientific books and lectures.

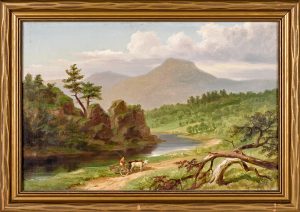

In 1845 Russell Smith took his first summer painting trip to the White Mountains of New Hampshire. He roamed all over the region, finding enough of interest to return for five more years. Just over the state line in Vermont, the Onion (Winooski) River began its ninety-five mile journey from its source to Lake Champlain. It is probable that during this period Smith set up his easel on the riverbank, near the mountain called Camel’s Hump, and sketched the study “On the Onion River”, for lot 22 in the May 21, 2021 Americana & International Auction at Pook & Pook.

At this point, Russell Smith emerged as a fully-formed landscape artist. His years of self-study, large-scale theatrical painting, and scientific drawing culminated in an individual style formed ahead of, and later influenced by, the Hudson River School painters. He was not in lock step with the movement. Like them, he appreciated the grandeur of landscape, and progressed from a precise recording of a scene to one concerned with light and mood. Unlike them, he did not paint with the same amount of detail and finish. He always painted as he saw, with atmosphere hanging between the foreground and distance. After inhaling a lifetime of art during two years in Europe, and a study of Claude Lorrain, his technique was set. As described by his son Xanthus: “My father’s characteristics as a painter are warm harmonious and often brilliant coloring, breadth of effect, composition tending to the Classical, and a certain looseness of handling founded on extended and careful study of that which he endeavored to express upon his canvasses.” His working method was to first make a pencil sketch, then an eight-by-ten inch oil study, and finally a finished picture. Highly organized, he catalogued sketches, studies, and notes. Years later, he could lay his hands on any sketch and work it up into a painting.

In 1851 Smith sold his home and took the whole family to Europe. He recorded impressions in copious notes throughout, beginning with the sea journey and the precise color of water. Landing in Wales, the wild and desolate scenery appealed to his romantic sensibilities. The months of May and June were spent in an “earthly bliss” of long family walks, picnics, and painting, and we can pinpoint the excursion that produced the later-finished oil painting lot 51 “Village of Llanberis, Wales, 1860”: “… we set off one fine morning, early in May… to go by Caernarvon through Llanberis pass and round to Capel Curig, a good day’s walk for the little folks, but was a charming day, temperate and bright… We made a halt again at the old Dolbadarn tower, climbed up its quaint stone stairway, where a fine view of all the interesting features of the grand scene, can be had, and the pencil was again busy with the lake and the portion of the view looking back towards Llanberis, a meagre looking stone village and quaint old church… In this day’s journey I saw some of the best scenery of Wales and got a much higher idea of its picturesqueness, beauty, and grandeur than I had entertained before. What I had learned of it previously was through the drawings and engravings of the English painters… and from their striving after effect in color and light and shade with an almost total neglect of structure, I was agreeably surprised and charmed with wonderful variety of form…”

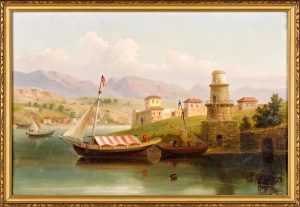

April, 1852 found Smith at lot 19 “Near Toulon, 1852”: “Sunset off Toulon. A bright clear sky as with us golden on the horizon running up through yellowish grey into warm blue at the top having orange and salmon clouds with warm shadows—all exactly as at home with a fine bright sunset. The sea looking towards the west is no longer a blue but a warm grey color. The surfaces of the waves which are perpendicular to the eye only are blue as they take on the blue of the upper eastern sky. But most of the other surface take more or less of the golden horizon or the salmon coloured clouds above. The Mediterranean (with a clear sky) is a deep inky blue but soft or mild and the properly inclined surfaces take on not only the soft warm color of the sky but also the mild orange color of the coast. There is nothing harsh or out of keeping in the whole scene.”

Returning to Philadelphia in 1853, Smith set about constructing his ideal country house. To the astonishment of all, he built a castle keep. It was either a tribute to the ruined keep at the old family home Rosslyn Castle, or the towers at the Old Port of Marseilles. (The stretch of road it is on is Roslyn Road, if that can be taken as a further clue.) From his romantic, ivy-clad tower, Lord Russell “could see from the top the entire horizon- a sweep of some two hundred miles in clear weather.” Smith denied castle-building, maintaining that he needed to build up, instead of out, as the surrounding land was too dear. He later purchased all of it. For the next twenty years, Russell Smith went from strength to strength, painting landscapes and returning to his theatrical beginnings. He had returned from Europe with over one hundred studies that he set to work finishing as paintings. Patrons beat a path to his castle door to buy his latest. The Philadelphia Academy of Music opened in 1857 and kept Smith busy painting drop and set curtains. He even had to build an addition to accommodate the curtains, which were thirty feet in height, and as much as fifty feet in length.

His children Xanthus and Mary became successful artists in their own right. Both attended the Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts. Xanthus became particularly famous, utilizing his wartime service in the Navy to specialize in historically accurate paintings of Civil War marine battle scenes. Lots 38 and 39 are both by Xanthus, bringing the total number of paintings in the May 21st sale by the Smith Family of Painters to five.

Russell Smith embodied the 19th century American success story, a tale worthy of the very stages he decorated. His life nearly spanned the century, from 1812 to 1896. His painting style remained original, regardless of the tides of change in the art world, and valued by his Philadelphia patrons. An immigrant, reliant upon the virtues of a superior work ethic, ability, and modesty, achieved happiness, respect, and riches, built his own fairytale castle, and lived happily ever after.

Pook & Pook is delighted to have a curtain call for the patriarch of this very talented Philadelphia family.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Lots 22 and 19 in the May 21, 2021 Americana & International Auction.

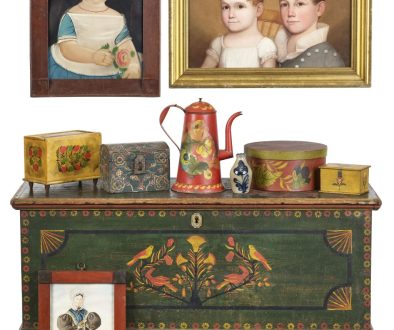

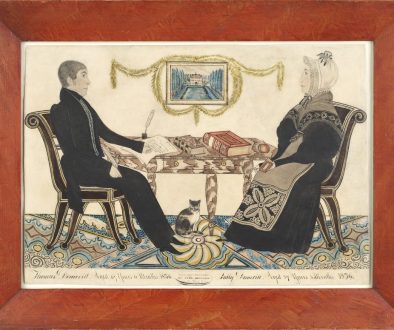

Examples by Xanthus Russell Smith in the May 21, 2021 Americana & International Auction.

Sources:

Lewis, Virginia E., “Russell Smith, Romantic Realist,” 1956, University of Pittsburgh Press.

Torchia, Robert, “The Smith Family Painters: A Series of Exhibitions,” 1998, Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art, Ursinus College.

Rowland, David, “Thalian Hall Lecture on Russell Smith,” August 6, 2013, Thalian Hall Center.