Up to snuff

Snuffboxes came into wide circulation with the increasing importance of tobacco use in the West. Tobacco was first prized as a medicine when first imported from the New World in the late 16th century. Europeans delighted in the effects of nicotine from the exotic tobacco plant, and the demand for tobacco grew. Snuff did not become popular in France until after the 1715 death of King Louis XIV, who disapproved of tobacco. By the 1730s, however, snuff was firmly at the center of fashionable French customs, and an important social aspect of the court.

Eighteenth century Paris produced the finest luxury goods in Europe. The entire Parisian economy was based on small, skilled artisan workshops. The personal goods produced included snuffboxes, miniature masterpieces that became as coveted as tobacco itself. Snuffboxes were the height of fashion, with the most elegant made of gold, often set with diamonds, enamels, and other precious materials– the more exotic, the better. A Parisian gold snuffbox was among the most expensive and desirable status symbols of the day. They were frequently presented as royal gifts to courtiers and ambassadors, and many were given for service to the crown.

Snuffboxes and snuff were important social indicators. Taking snuff evolved into elegant solitary acts, in which was displayed as much style and grace as possible, and group activities, where “the act of handling the box and offering snuff evolved into a secret code, the ‘language of the tabatiere.’”(Victoria & Albert Museum, Gold boxes) Pity the poor lover of Carl Alexander von Lothringen, who had to interpret the signal recorded in his diary that “taking snuff, and then pretending to flick traces of it from his coat or fur tippet, was his way of asking his beloved whether she would attend a ball.” (V&A, Gold boxes) The gold boxes were also given on occasions of marriage and in friendship amongst powerful and influential people, with many examples known to have been owned by historically important 18th c. figures.

This Nicolas Marguerit oval snuffbox, lot 8044, is an example of the pre-eminence of Parisian goldsmiths. Decorated in three colors of gold, the lid is engraved with a fine guilloche wave pattern surrounded by a border of symmetrical leaf swags. The side of the box with four panels of the same pattern below a frieze of stylized laurel leaves and flowers. The side panels are divided by vertical ribbon-topped columns with neoclassical motifs such as a torch and quiver, and a lute and horn, as well as pastoral motifs such as a basket and crook, and a bagpipe, staff, and hat. It is marked inside the lid, inside the base, and on the rim for Nicolas Marguerit (fl. 1763-1790), Paris. Marguerit was an apprentice until 1751 and earned his Master’s status on January 17, 1763, endorsed by Germain Chaye. He was active until 1790, recorded at Carrefour des Trois Maries in 1774, rue de Montmorency in 1782, at Place de Trois Maries in 1783-87, and at rue Hillerin Bertin from 1788-1790. Gold snuffboxes by Nicolas Marguerit can be found in collections such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum Collection, Moscow.

A handwritten note kept inside the box reads: “This snuffbox was presented to J.H. Cochrane of Rochsoles by the Duchess of Hamilton. A letter from the Duchess to J.H.C. will be found in the Family Book referring to this. H.L.C.” It is not known exactly what the Cochrane Family Book reveals, crucially, whether this snuffbox was given in 1768, or purchased and presented to Cochrane at a later date, but we do know a little about the Duchess of Hamilton of the period, Elizabeth Gunning (1733-1790).

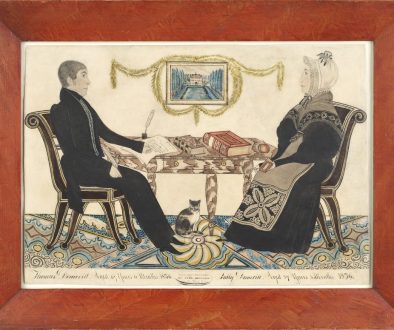

Elizabeth Gunning, Duchess of Hamilton, Gavin Hamilton, 1753. Photo credit: Scottish National Gallery.

Elizabeth Gunning was a real-life Cinderella story, an Anglo-Irish beauty born into relative obscurity. Elizabeth and her sister caused a sensation in 1750 when they were presented to the Court. Renowned for their beauty, their fame spread throughout London. Their lives became a whirl of grand balls and soirees. At a Valentine’s Ball at Bedford House in 1752 Elizabeth met James Hamilton, 6th Duke of Hamilton. James Hamilton was young and goodlooking, but dissolute, and full of bad ideas. They were married that night, at 12:30, at Mayfair Chapel where a marriage license was not required. Such was their haste, a bedcurtain ring had to serve as a wedding band. Horace Walpole chronicled their brief courtship. It is well worth a read.

From the Letters of Horace Walpole, 27 Feb, 1752: “I write this as a sort of letter of form on the occasion, for there is nothing worth telling you. The event that has made most noise since my last, is the extempore wedding of the youngest of the two Gunnings, who have made so vehement a noise. Lord Coventry, a grave young lord, of the remains of the patriot breed, has long dangled after the eldest, virtuously with regard to her virtue, not very honourably with regard to his own credit. About six weeks ago Duke Hamilton, the very reverse of the Earl, hot, debauched, extravagant, and equally damaged in his fortune and person, fell in love with the youngest at the masquerade, and determined to marry her in the spring. About a fortnight since, at an immense assembly at my Lord Chesterfield’s made to show the house, which is really magnificent, Duke Hamilton made violent love at one end of the room, while he was playing at pharaoh at the other end; that is, he saw neither the bank nor his own cards, which were of three hundred pounds each: he soon lost a thousand. I own I was so little a professor in love, that I thought all this parade looked ill for the poor girl, and could not conceive, if he was so much engaged with his mistress as to disregard such sums, why he played at all. However, two nights afterwards, being left alone with her while her mother and sister were at Bedford House, he found himself so impatient, that he sent for a parson. The doctor refused to perform the ceremony without license or ring: the Duke swore he would send for the Archbishop – at last they were married with a ring of the bed-curtain, at half an hour after twelve at night, at Mayfair chapel. The Scotch are enraged, the women mad that so much beauty has had its effect, and what is most silly, my Lord Coventry declares he now will marry the other.”

Elizabeth’s celebrity was such that she drew crowds of onlookers wherever she went. After the Duke died in 1758, she married John Campbell, the future of Argyll, and later was Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Charlotte. In 1776 she was made Baroness of Hamilton in her own right. While research into the Cochrane Family Book should reveal which Duchess of Hamilton presented this snuffbox with its bagpipe motif, a very probable first owner was the glamorous Elizabeth Gunning.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence