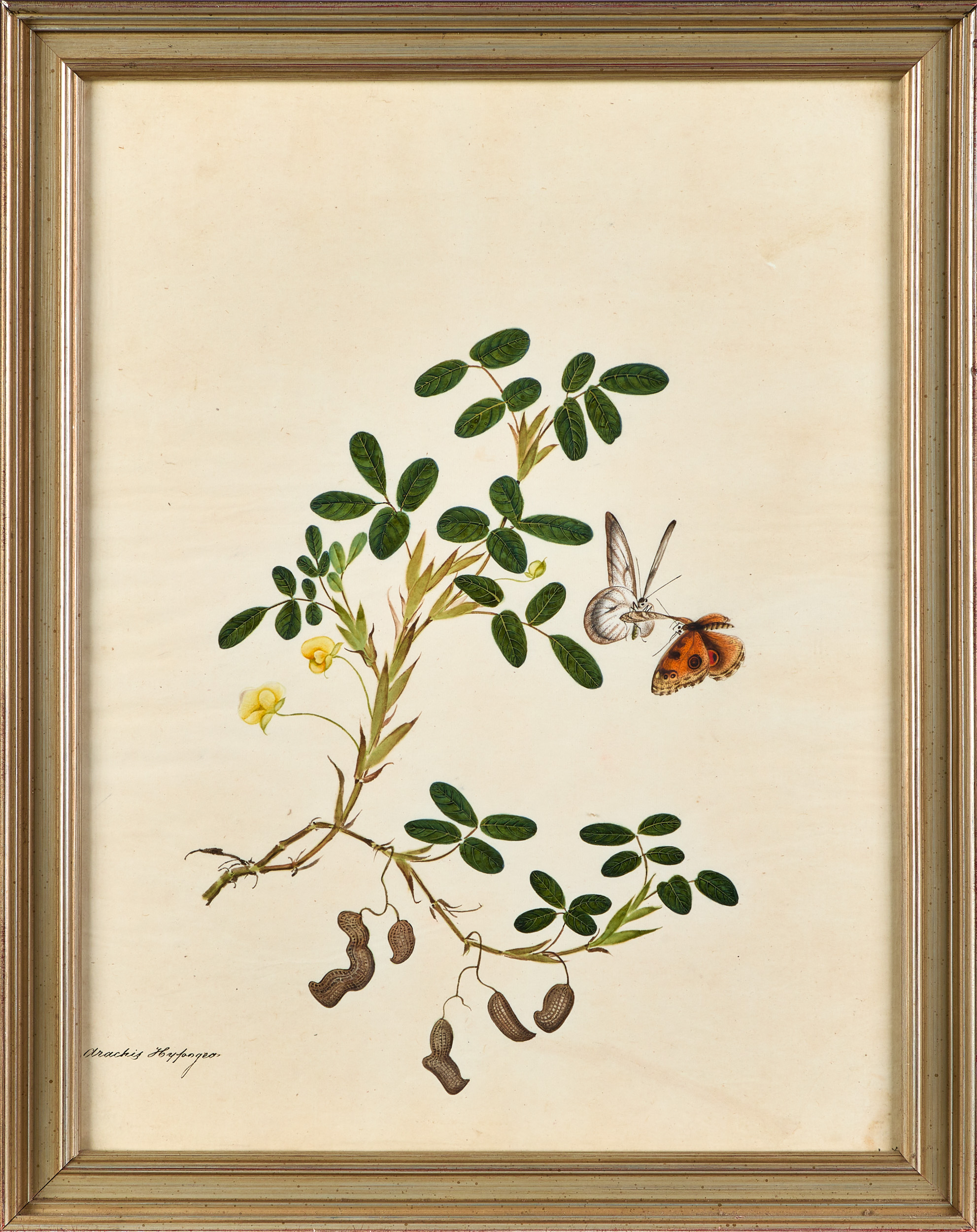

Chinese Botanical Watercolors

On October 6th, Pook & Pook will auction Chinese botanical watercolors from the Estate of Peter Tillou. Three pairs of watercolors, lots #344, 345, and 346, attributed to Win Achun and other artists, have provenance from Peter Tillou, “According to an early auction catalogue clipping the collection was ‘executed expressly for the Late J. Roberts, Esq. (A Director and Chairman of the East India Company) and are sold by order of his executors. It would be difficult to convey an adequate idea of the taste, beauty and spirit with which the Drawings are executed, and I am assured by a very competent judge who was in China, when the Drawings were made, that their fidelity is equal to their beauty. All the Botanical Drawings were submitted by the Artist to the inspection and received the approbation of Mr. Kerr, the Botanist, who was sent from Kew to China by his Britannic Majesty.’ The collection was also listed in the auction catalogue of Wentworth Henry Canning, 2nd Viscount Allendale.” (Also see Christies London sale 5792, lot 14, The Property of the Beaumont Family, 29 April, 1997.) A fourth entry, lot #437, is a trio of Chinese watercolors of fruit trees, showing peaches, pomelos, and possibly loquats.

Beautiful products of a collision between worlds, the watercolors and gouaches were painted by artists of the ancient academic tradition of Chinese botanical painting, first recorded in the Han Dynasty; to the detailed specifications of Western naturalists and botanists fueled by the Enlightenment, who were exploring and attempting to understand the world through science.

In the scientific awakening of the Enlightenment, a knowledge of botany was part of a well-rounded individual’s education. In 1751 Carl Linnaeus published his system of taxonomy, giving scientists a common language of classification to use. After Captain Cook’s 1768 voyage, Joseph Banks convinced King George III to turn his royal gardens at Kew into a botanical collection and research institution for the nation. The first colonial botanic garden was established in 1765 by the East Indian Company on St. Vincent in the West Indies. In the effort to break the Dutch spice monopoly, a Calcutta garden was founded in 1787. Eventually a network of gardens spanned the globe, proving vital to the British Empire, allowing crops like rubber and quinine to be collected and grown. The botanical gardens were imperial tools, intended for the reproduction of useful plants for the military, colonists, and trade. Crucial to the future expansion of the British Empire would be a supply of quinine. Economic crops like tea, tobacco, cotton, and, infamously, opium, were grown. Also centers for research, their plants, seeds, and information sailed the high seas. The gardener-botanists from Kew transported spices, breadfruit, coffee, quinine, and rubber around the globe, as well as newly discovered ornamental plants. Enlightenment thinking also transformed economics, producing growth through the application of science. Enriching trade by the introduction of new plantation crops for colonies became one of the main sources of wealth for the British Empire. Local substitutes for imports stemmed the drain of silver from the exchequer. William Bligh, captain of the HMS Bounty, was transporting breadfruit tree cuttings from Tahiti to the St. Vincent garden for Joseph Banks when his journey was so famously interrupted.

Banks appointed William Kerr to be Kew’s botanist in China, making Kerr the first western professional plant hunter. Kerr was sent to Canton with the British East India Company, which held a monopoly charter on eastern trade. Banks equipped Kerr with a set of botanically accurate watercolors. Made in Canton in the late 1700’s by Chinese artists supervised by John Bradby Blake, an East India Company supercargo, the drawings detailed plant, flower, fruits, and seeds, and were labeled with names in both Western and Chinese characters. “He was to look out for unusual plants, or especially those that grew in China’s more northerly provinces, which would have the best chance of surviving England’s climate… the main document he entrusted to him was the Book of Chinese Drawings which, as Banks put it, ‘will Enable you to Enquire after many Plants that might not possibly have become known to you.” 1,2

The world Kerr sailed into was governed by the Canton System (1757-1842), a Qing protectionist arrangement designed to control trade with the West. All trade and movement of westerners was confined to a small warehouse district on the Pearl River in the southern port of Canton, specifically to thirteen large buildings called hongs, or Factories, and transacted only with officially licensed Chinese merchants, the Cohongs. Foreign merchants were not permitted permanent residence at Canton. They were allowed to stay at the Factories only during the shipping season, relocating to Macao during the offseason. Kerr lived in the British hong with the other officers of the British East India Company. The Cohongs maintained elaborate gardens and introduced their clients, who were otherwise confined to the Factory compounds, to many previously unknown plant specimens. A contemporary of Kerr in Canton, the Cohong Howqua had just inherited his father’s company in 1801 and was on his way to becoming the richest man on earth. Howqua’s famous garden was an impressive space for entertaining his trading guests, with a river entrance, a nursery and potting sheds on the grounds.6 Henan had been a popular location for garden making since the Ming dynasty, and the availability of potted exotic plants, flowers, and dwarf trees produced in the neighboring nurseries, explains why Howqua, and other local gardeners, possessed such a wide collection of plants. In Cantonese gardens, flowerpots were arranged in ever-changing combinations.3 Aesthetic gardens with precious specimens were traditionally a hobby of Chinese scholars, who deemed commercial gardening vulgar. “The Hong merchants’ motives for collecting plants were not so different from their Western associates. Foremost was a desire to acquire a status symbol – Chinese literati at the top of the social hierarchy in China frequently kept gardens with rare flowers, and the Hong merchants wanted to attain such social circles… For the Western plant enthusiasts and collectors, finding a new species and bringing it home carried significant prestige, sometimes accompanied by substantial monetary gain.”4,5 Foreigners had to rely on a network of Chinese contacts to gather local plants, which they then frequently grew in Macao. “Contrarily to scholar or imperial gardens the Hong merchants’ pleasure grounds and Guangzhou nurseries contained plenty of plants to buy, ready to be carried in pots.”4

“Kerr arrived in Canton in October 1803 and quickly settled down, growing plants in his own garden and choosing which to send to Kew, using the Book as a guide…” Facilitated by the Hong merchants, Kerr gathered specimens from the plant nurseries in Huadi.5 Robert Fortune later described Fa Tee Gardens, “the flowery land, as the name implies”, consisting of about a dozen small nurseries. “Potted plants were mostly placed in rows alongside narrow paved walks, with houses for gardeners at the entrance. There were stock-grounds where planting out was done and also here the first process of dwarfing their celebrated trees is put into operation… These gardens were most beautiful in spring with a brilliant display of tree peonies, camellias, roses and particularly azaleas… Every garden was one mass of bloom… and full of the scents of olea fragrans and Magnolia fuscata.” On New Year’s Day Fortune “saw boats on the river laden with branches of peach and plum blossom, camellias, cockscombs, magnolia and enkianthus brought down from the hills, and at every street corner jonquils grown in water with a few white stones were for sale. Large parties of young Chinese crowded floral boats bound for the Fa Tee Gardens.”6 China’s native botanical bounty included oranges, peonies, chrysanthemums, azaleas, rhododendrons, camellias, magnolias, lilacs, and tea, to name a few.

John Roberts (1739-1810) was no ordinary wealthy customer ordering a set of illustrations to boost the prestige of his library, and it is no coincidence that he ordered them from William Kerr. From 1764 to 1808, John Roberts was alternately the Chairman, or a Director, of the British East India Company. “In London, the Court of Directors, with Banks’s assistance and support, had something in mind for themselves. They wanted Kerr to put together a set of drawings of Chinese plants to be displayed in the newly-founded India Museum, adjoining the Company’s headquarters. In Canton, Kerr soon found a Chinese artist to produce the drawings… The first set of drawings was a big hit in London and Kerr arranged for a second set to be made. These arrived in 1806, two years after the first set – nearly 400 drawings in total. These were the first Chinese drawings the Company commissioned.”1 The most powerful corporation the world had ever known, the Company was at the peak of its power. Roberts became Director one year prior to the Mughal emperor relinquishing the right to collect taxes and duties to the Company, which laid it’s foundations of empire. By 1800, it ruled over millions of people and maintained a standing army of over 200,000 soldiers. It was more powerful than most countries, and Roberts and the Directors more powerful than many rulers. In the late 18th century, high-ranking Company employees commissioned their own collections of natural history paintings.8 Influenced by Banks, and commissioner of botanical works on behalf of the Company, Roberts would have naturally desired a set for his own library, reminders of the Company’s, and his own, role in botanical history.

Kerr worked in Canton for eight years, discovering many plants in local Chinese gardens and nurseries. The job was both challenging and lonely. “Despite the impressive title of Royal Gardener, William Kerr had ‘no one…to associate with’ in the Factory…the small salary Kerr received from Kew Gardens also trapped him in disgrace. While the sum of £100 a year might have been a passable income for a gardener in England, in Western China, it was a pittance.”5 A Company contemporary in Canton, John Livingstone later reported that Kerr had been “sent… with the most carefully contrived chests and boxes, but with so small a salary as to lose respect in the eyes of his Chinese assistants.”7 Kerr’s situation would have also been made difficult by the Company illegally smuggling opium into the local market, which began a decades-long conflict. Afterwards Kerr moved to Ceylon as the superintendent of its colonial botanical garden and died in 1814, reportedly from opium addiction. Writing about Canton decades later, Fortune visited “the garden which at one time belonged to the East India Company and which was still in existence: ‘It is but a small plot of ground on the river side, not more than sixty paces each way’, now neglected.”7 Kerr’s botanic legacy has been more lasting than his garden. He sent back to Britain 238 plants new to science.

Kerr also left an artistic legacy. In the botanical watercolors produced for Kerr, “the boundary between ‘fine art’ and ‘scientific documentation’ blurred.”9 Prized for their practical contributions to botanical science, they are also highly regarded as a continuation of an ancient and evolved art form. Nearly a millennia after the first Han bird and flower paintings, 12th century Sung Dynasty artists began to combine lyric poetry and flower painting, evolving a complex style as symbolic and metaphoric as it was aesthetic. Painted without background or setting, single blossoms or branches became objects of contemplation. Layers of meaning ranged from beauty, purity, scholarship, nobility, and asceticism to emotional expressions like resilience and the search for perfection on a personal level.10 Chinese artists applied their skill to the westerners’ requirements for botanic accuracy and comprehensive detail. The resulting art form of botanical illustrations are a synthesis of Chinese art and the scientific observation of the Enlightenment. In later years, “the botanical role for Cantonese artists in the 19th century was largely that of decorative ‘export’ art as upmarket souvenirs. These included flowers and fruits produced in huge quantities painted on the smooth, brittle surface of ‘paper’ made from the pith of Broussonetia papyrifera.”9 Future works were usually made from templates, based on the early originals. The nearly-translucent quality of pith paper facilitated a method of creation that included tracing, and then painting over the pattern. Here are four lots of early originals, works of both beauty and historical significance, the artists working in tandem with Kerr to get every last detail perfect for posterity. They are the results of the artists and botanist combined search for perfection—their lyricism beautiful to contemplate.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Sources:

Kew Botanic Gardens

1 Goodman, J. & Jarvis, C., The John Bradby Blake Drawings in the Natural History Museum, London: Joseph Banks Puts them to Work, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, 2017, vol. 34.

2 Banks to Kerr, April 18, 1803, State Library of New South Wales, Papers of Sir Joseph Banks.)

3 Richard, J.C., Uncovering the garden of the richest man on earth in 19th c. Canton: Howqua’s garden in Honam, China, Garden History, 2015, vol. 43.

4 Richard, J. & Woudstra, J., “Throughly Chinese” Revealing the plants of the Hong merchants’ gardens through John Bradby Blake’s paintings, Curtis’ Botanical Magazine, 2018.

5 Fa-ti Fan, British Naturalists in Qing China: Science, Empire, and Cultural Encounter, Harvard UP, 2004.

6 Fortune, R., Three Years Wanderings in China, 1847.

7 Le Rougetel, H., The Fa Tee Nurseries of South China, Garden History, 1982, vol. 10.

8 Archer, M., Natural History Drawings in the Indian Office Library, HMSO London, 1962.)

9 Williams, I. & Ching, May Bo, Created in Canton: Chinese Export Watercolors on Pith, Lingan Art Publishing, 2014.

10 Harrist, R., Ch’ien Hsuan’s “Pear Blossoms”: The Tradition of Flower Painting and Poetry from Sung to Yuan, Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 22, 1987.