Metamorphosis Femina Physicus

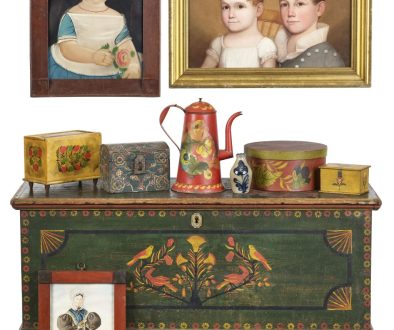

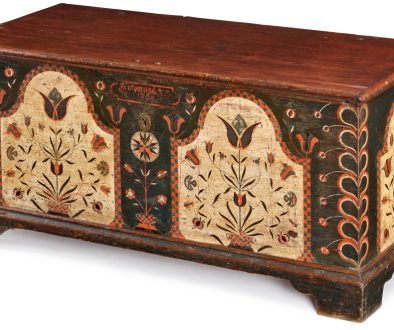

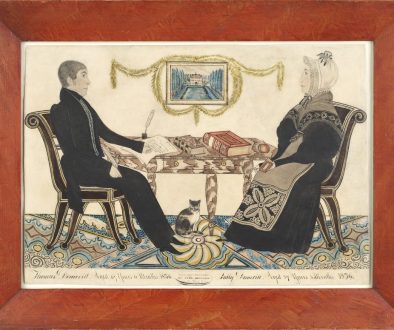

Where do 17th century art and science collide with a Doomsday cult? On the pages of “Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium,” a lavish folio of plant and insect engravings published in 1705 Amsterdam by the world’s first entomologist Maria Sibylla Merian, and one of the most beautiful natural history books ever published. Two hand-colored engravings from this work are featured in our January 30th International sale. They are exquisite collector’s objects with wide-ranging significance.

Born in Frankfurt in 1647 to a family of engravers and artists, Maria Sibylla Merian learned to draw and paint flowers at home. Always distracted by the insects she found, she included a bug in every picture. Marrying one of her father’s apprentices at the age of eighteen, she began teaching painting and needlework to wealthy young women. Her studies led to publication of a book on her special interest, butterflies. Her approach was revolutionary. Each beautiful page was the complete life cycle of a butterfly, in its habitat, drawn from life. Little was known about insects at this time. It was still widely held that insects were born of vapors and rotting plant and animal life, spontaneously generated. Linnaeus was not to classify Insecta for decades (and when he did, he would reference Merian’s books). There were as yet no studies of the relationship between insects and plants.

Merian’s independent-minded behavior did not stop there. By 1685 she moved with her two children and widowed mother to a Labadist Protestant commune at Walta castle in the Netherlands. Her husband made attempts to retrieve her, but she successfully divorced him in 1692. He was a Catholic, and Merian had joined a Protestant sect believing in disciplined, communal isolationism, an attempt to recreate the experience of first century Christians. While it is hard to tell what most bound Merian to the commune, it is known she became obsessed with its collection of exotic tropical insects. The castle was owned by Cornelius van Sommelsdijk, who had just purchased one-third of the colony of Suriname, recently acquired from England in exchange for New Amsterdam, and become its Governor.

Moving to Amsterdam and setting up her own workshop, Merian raised funds for a scientific expedition to Suriname to study insects. She sailed in 1699, accompanied only by one of her daughters. It was one of the very first solely scientific expeditions, and the first for a woman. Reaching South America took two months at sea, and to travel upriver to the Labadist colony of Providentia was four days of rowing. Providentia sat deep in the jungle, isolated from corrupting influences, and waiting for the coming of the Apocalypse. (Established in 1675, by 1699 all of its colonists had died from disease and violence except a few hardy zealots and slaves. Van Sommelsdijk himself was murdered in 1688.) Merian spent the next two years studying and drawing the plants and animals, voyaging up and down the river between equatorial jungle and sugar plantations. Living closely with the slaves, she paid them to bring her plant and insect specimens, and she recorded eyewitness accounts of their treatment and hardship. Merian did not escape the Providentia affliction, contracting an illness which forced her return after two years’ work and was to plague her for the remainder of her life.

In Amsterdam, she set about creating books from her notes, drawings, and specimens. Her strength depleted by fever, she only produced three of her book’s sixty engravings, guiding engravers to adapt the rest. The plates were then painted by Merian and her daughters. Her magnum opus, “Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium” was published in 1705 to wide acclaim. Merian’s artistic sensibility, her scientific observations, and her pioneering work to present forms of life wholly unknown to Western science captivated society. Fat caterpillars clung to succulent jungle plants, tropical flowers burst forth in sunset hues, and feathery moths danced across the pages. Passionflowers bloomed, tarantulas devoured birds. The book was a triumph of art as well as a revolution in science. Merian’s books were collected by the finest libraries in the world, and when she died in 1717, her entire works were purchased by Tsar Peter the Great. Here are two that can be yours.

by: Cynthia Lawrence