…Blue, blue, electric blue…

…Blue, blue, electric blue

That’s the color of my room

Where I will live

Blue, blue…

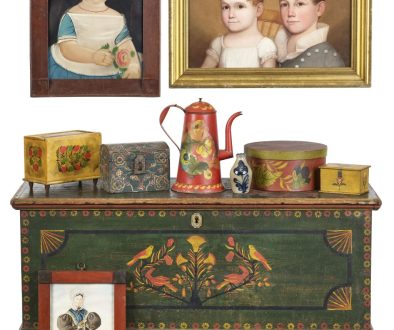

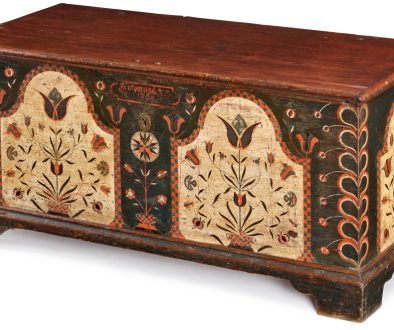

The auction hall at Pook & Pook this week is full of 18th and 19th century painted furniture. There are pieces in ochre, salmon, green, and red, but the ones I love are the cool blues. The words of David Bowie running through my head, I take a deep breath, relax, and take in the sight. The painted furniture, textiles, glass and mocha are an ocean of blue: robin’s egg, cobalt, aqua, teal, navy, turquoise, midnight and sky, to name a few.

This is remarkable, since it was neither easy nor inexpensive to paint things blue in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Paint and brushes had to be made from scratch, bristles gotten from an unwilling badger. Pigments, derived from organic sources, were ground using a hand-held stone muller against a marble slab. The finer the grind, the more saturated the paint color would be. Indigo, azurite, and expensive lapis lazuli were ground to obtain blue. Pigments were then mixed with a binder to form the paint. Linseed oil was the most common medium, followed by distemper, a binder of hide glue and water. During the Revolutionary War when linseed oil was scarce, many opted for a paint made from milk, lime, and pigment, in which casein was the binder. Milk paint was significantly cheaper than oil, and easier to make than distemper. Finally, if a paint was to be opaque, rather than a transparent varnish, a little lead would be added. For centuries, these were the methods and ingredients for the making of paint.

In 1706, the first modern synthetic pigment was created, Prussian blue. It was discovered accidentally by German alchemist Johan Dippel, who had been trying to transmute base metal into gold, and a painter named Diesbach. Easily made by combining oxblood, potash, and iron sulfate to create iron ferrocyanide, it became widely available by 1724. Depending how much pigment was used, the color ranged from nearly black to a bright blue with a greenish tint. Mixed with lead white, pale blues could be created. The pigment became very popular. George Washington painted the West Parlor of Mount Vernon Prussian blue.

Old hand-ground pigments and hand-mixed paints create interesting surfaces. The uneven distribution of pigment in the paint, and the uneven opacity and texture create a sense of depth and character. As seen in the mosaic above, no two pieces of furniture in this room are the same shade, but they are all lovely. I can imagine sitting in a room of them, surrounded by these blue sentinels of history, waiting for the gift of sound and vision.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence