Brotherly Love

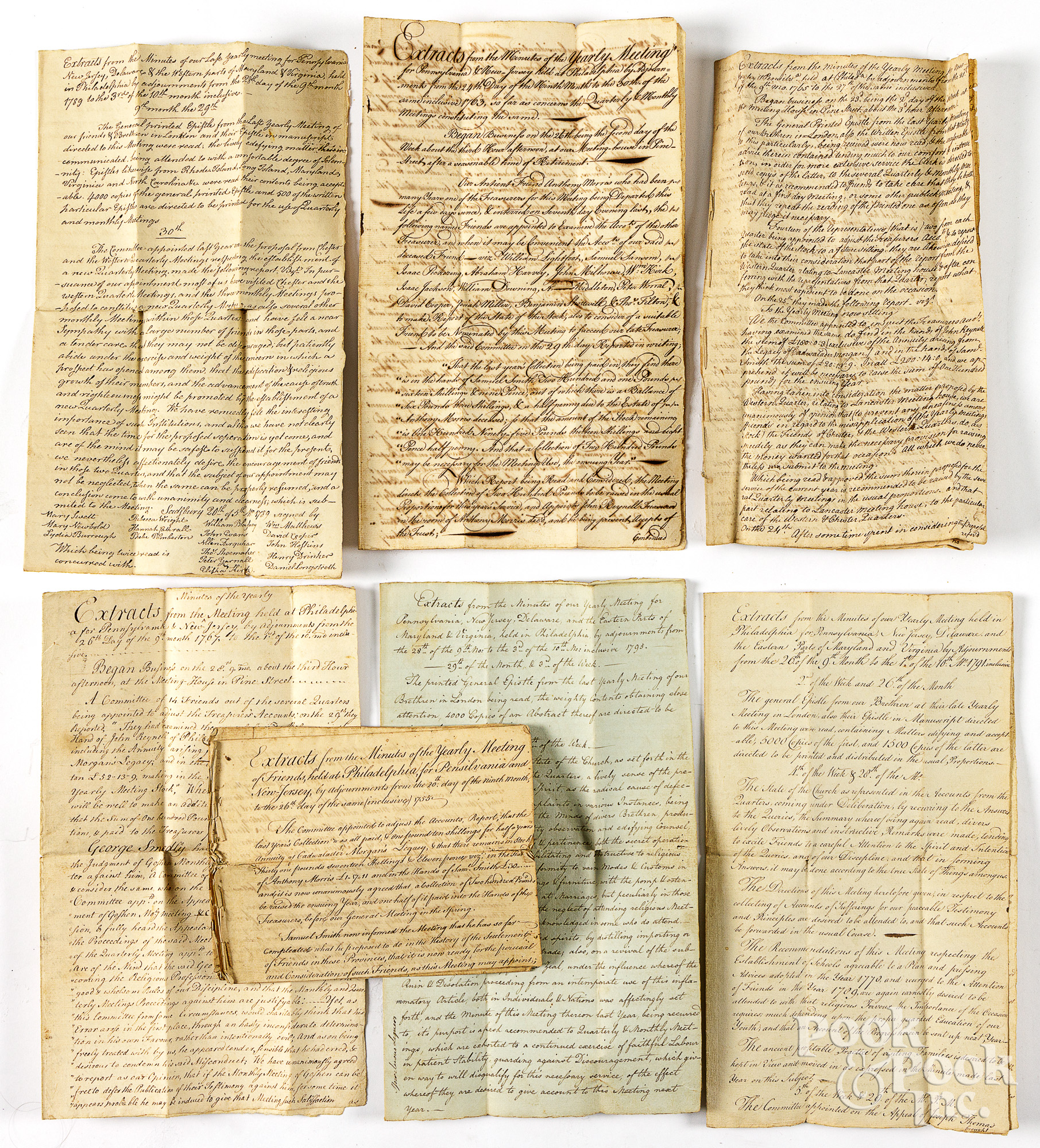

“We Salute you in Brotherly Love” begins a 1745 Epistle from the Quaker yearly Meeting in London. Handwritten by John Gurney, it reads like a sermon, exhorting the Friends to live in the ways of Holiness and Truth. It is evident in dozens of Epistles recorded over the next one hundred years that the Quakers of Philadelphia and the surrounding areas attempted to do exactly that. Divided into ten lots, #5939-5948, this fascinating collection of meeting notes charts the lives, challenges, and hopes of a Who’s Who of 18th and early 19th century Philadelphia area Quakers.

Quaker children dwelling in outlying areas were at risk, being “placed in with those not in membership with us” for schooling and being unduly influenced by “Evil Examples”. To address this issue, in 1794 plans were realized “relating to the Establishment of a Boarding School… in some suitable place or places in the Country… the use and benefit whereof, to be confined to the Children of Friends,” with “the amount of about five thousand pounds to be applied to the promoting of such an Establishment.” The committee assigned to plan the school, set rules and regulations, allocate money to purchase land and erect buildings would report yearly progress, and construct what is almost certainly the Westtown School. The Extracts trace their progress. In 1798, “the necessary buildings are mostly erected, and nearly finished, so as to be ready to receive children as soon as suitable persons may be engaged to instruct them, and superintend the economy of the house, etc.” In 1799, the boarding school reported admission of sixty girls and seventy-three boys.

The Quaker desire for peaceful coexistence led to concern for the plight of the “Distressed Inhabitants of the Wilderness”, and the call for a Native American school. A 1795 Extract reported “… there are loud calls for our benevolence & charitable exertions to promote amongst them the principles of Agriculture and useful mechanic employments” and a call to raise funds towards that purpose, a school. A later 1827 report from “The Committee, on whom is devolved the concern for the gradual civilization of the Indian natives” informs the Friends that “five Friends continue at the settlement at Tunesassah, endeavouring to instruct the natives in the arts of civilized life; for which purpose, two schools, one for boys and the other for girls, have been continued there…” Instruction in agriculture was undermined by “the circumstances attending these people at this time not being calculated to encourage them to exertions of this kind, as, since last year, the Seneca nation have been induced to part with very large bodies of their lands in different places…and it is feared this may be a prelude to their parting with the remainder at no very distant period. Notwithstanding these discouraging circumstances, it is believed, that by continuing to aid and assist these poor injured people, as long as there is any prospect of benefit, the objects contemplated by Society will be best promoted.”

The first religious group to oppose slavery, the subject was a constant theme. The 1767 Philadelphia Meeting notes “the Subject of some Friends neglecting the Christian Education of Negroes, & other Slaves in their possession, & detaining them in Bondage, hath been weightily under our consideration at this Time: It is again Recommended, that the care of Friends relating to those oppressed People in these particulars, may not be omitted; but that we proceed in true Love, to labour to excite to an upright Discharge of our Christian Duty towards them.” A much later 1827 Epistle reports an appeal by Carolina Quakers for funds for relocation, “there are 44 persons of colour who have intermarried with slaves and have 79 children. There are 20 married to those legally free, and have 50 children. That there are 316 disposed to remove to Liberia; 101 to Ohio and Indiana; 99 desire to remain where they now are; 15 choose to go to Philadelphia, and 86 are entangled in lawsuits… The total expense which will attend their transportation, it is believed, will not be less than from eight to ten thousand dollars…”

In a 1794 yearly Quaker meeting Extract, there is much attention devoted to spirits: both the purification of spirit brought about by baptism, and the perennial problem of distilled spirits, a subject “long painfully exercising to the Body.” Quakers were prohibited from “importing, or vending, distilled spirituous liquors, either on their own account or as agents for others, or distill or retail such liquors, or sell or grind grain for the use of Distillation.” The “Monthly Meetings should deal with them as other offenders, and… be at liberty to declare their Disunity with them.” Of course, this was a losing battle. By the 1797 Extract, the committee tasked with spirituous liquors “report we… are of the mind that not much, if any, advancement has been made in our Testimony against the use of those Liquors…”

A 1753 Epistle contains a wonderful reminder for Quakers to avoid other hazards “… many men amongst us putting on Extravagant Wiggs and wearing their Hats and Cloaths after the vain Fashions, unbecoming the Gravity of Religious People: and too many Women decking themselves with costly and Gaudy Apparel Gold Chains, Lockets, Necklaces, and Gold Watches exposed to open view; which shew more of Pride and Ostentation than for use and Service, besides their vain imitation of that immodest Fashion of going with naked Necks and Breasts and wearing hooped Petticoats; inconsistent with that modesty which should adorn their Sex, and did adorn the holy Women of Old… And in like Vanity of Mind divers amongst us run into great Extravagancies in the Furniture of their Houses… it does not become the Gravity of our Profesion, or any under it, to run into every new, vain, Fantastick mode or Fashion but to keep to that which is modest, decent, plain and useful… And that Parents in the Tender Years of their Children would not adorn them with Gaudy Apparel…”

The life of Thomas “Squire” Cheyney illustrates the difficulty of being a Quaker, who cannot take oaths, during those tumultuous times. A 1767 Epistle from London is written by Cheyney almost a decade before he was dismissed from the Quakers for enlisting. Cheyney became a sublieutenant for Chester County during the Revolutionary War. Serving from 1777-1783, his participation was significant, passing vital information to General George Washington of British troop movements. True to his Quaker heritage, Cheyney later founded the first African-American institution of higher learning in the United States.

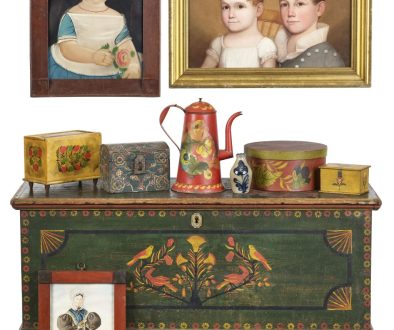

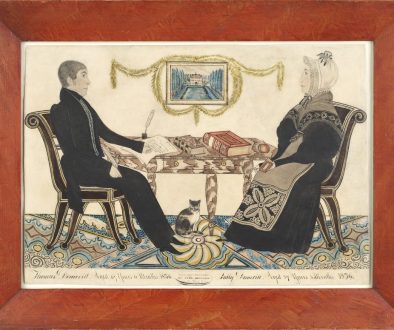

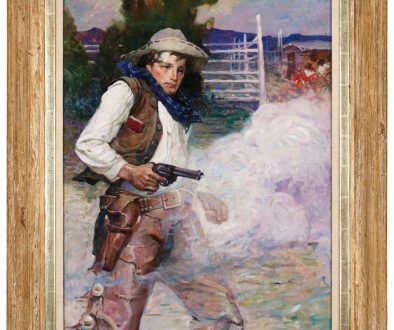

Please join us to preview the February 19th and 20th sale, or visit us online at www.pookandpook.com to view these items and many other exciting finds. Whether it is an Epistle exhorting forbearance, or a diamond wristwatch, it is guaranteed that that you will be tempted by something.

by Cynthia Beech Lawrence