NEWS

Press Release – January 2026 Americana Auction

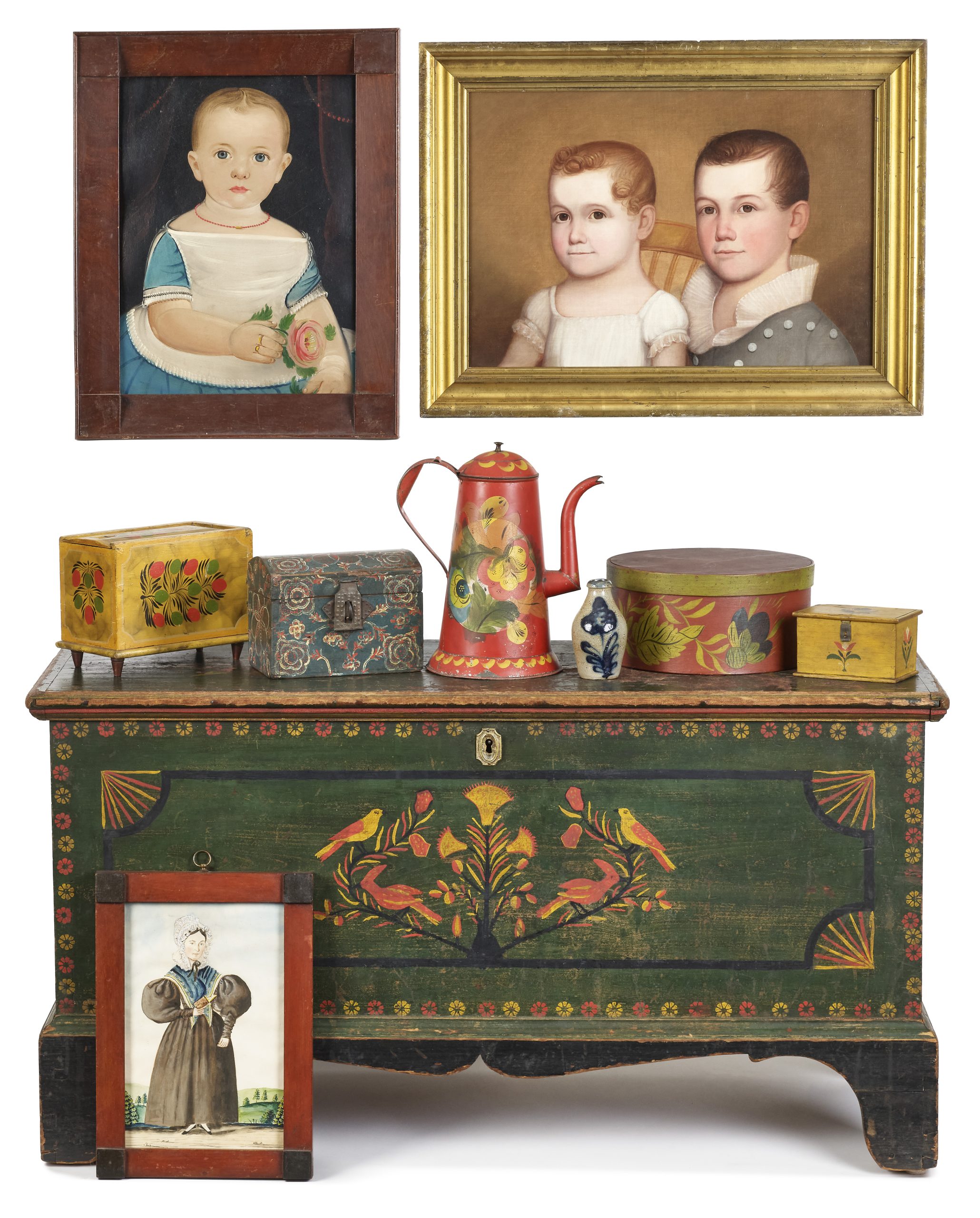

The Americana sale at Pook & Pook to be held January 14-16, 2026, will feature an extraordinary array of furniture and decorative arts from five large collections and many private consignors.

The sale opens with 400 lots of American Folk Art and Antiques from the Collection of the late Grant H. Griswold, of Raphine, Virginia. Assembled over decades by Grant and his wife Josephine, with guidance from leading antique dealers, the many exceptional objects are distinguished by strong provenance and exhibition and publication history. Highlights include folk art portraits by the earliest American itinerant artists: William Matthew Prior, James Sanford Ellsworth, Joseph H. Davis, Ruth Henshaw Bascom, Jasper Miles, Rufus Porter, and Jacob Maentel. A painted overmantel mirror is attributed to Winthrop Chandler, regarded as the first American painter of landscapes. An extensive collection of boxes includes examples from the Compass Artist, Weber, and pantry boxes from Boone County, Missouri. Furniture spans Pennsylvania and New England, including a diminutive Mahantongo Valley painted blanket chest; painted dower chests; the Trego-Fell family William & Mary painted poplar tripod table; a New Hampshire stained maple tall chest attributed to Samuel Dunlap of Salisbury; an Essex Massachusetts Chippendale birch chest on chest, possibly from the shop of John Chipman; a rare Rhode Island Queen Anne maple tuck-away table; a diminutive Connecticut William and Mary maple tavern table; and a noted Connecticut painted spoon rack. Windsor seating features the important Elisha Dyer set of six Rhode Island braced bowback chairs, possibly made by Elisha’s cousin, Rufus Dyer, and a rare pair of footstools attributed to Ebenezer B. Tracy. Decorative arts include a Joseph Lehn cup and saucer, and two outstanding red Pennsylvania toleware coffeepots.

Yvonne and the late Carl DePaulis, noted collectors of Southeastern Pennsylvania German furniture and decorative arts, acquired antiques throughout Berks, York, Lancaster, and Somerset counties. Among many treasures are a sulphur-inlaid schrank, a unicorn-decorated dower chest, and a group of Pennsylvania wrought iron betty lamps by John Long, Peter Derr, Joseph Stanem, and J. Schmidt. Woodcarvings include pieces by Joseph Lehn, Wilhelm Schimmel, John Reber, and Joseph Moyer.

The Hollenbaugh Collection, also rooted in Southeastern Pennsylvania, offers a fine collection of hunting pouches and powder horns. Its highlight is a Philadelphia pre-Revolutionary War stain-decorated powder horn. The Darby Collection focuses on redware, stoneware, and baskets, including a vibrant toleware document box and a Pennsylvania presentation stoneware beehive still bank attributed to Richard Remmey, Philadelphia.

The sale features the first of three installments of one of the largest privately held collections of European brass candlesticks, formed by Mike Luna of Taylor Ridge, Illinois. Over one hundred lots of brass and wrought iron lighting devices span Romanesque through Georgian periods. Highlights include an English Tudor chalice-and-paten candlestick, an English brass trumpet stick, and North West European examples in Gothic, pricket, and early tripod forms. Among the earliest is a Romanesque miniature bronze goat-form candleholder. An exceptionally fine pair of Georgian swirl base candlesticks, and a rare pair of massive Georgian paktong candlesticks represent the later periods.

Many outstanding items in the sale are from private collections. Furniture highlights include a George I double-domed walnut and burl veneer secretary bookcase; a Philadelphia Chippendale mahogany pie crust tea table attributed to the Garvan Carver; and a Soap Hollow, Somerset County Pennsylvania painted blanket chest.

Tall case clocks from the Crow family of Wilmington include both George Crow Queen Anne and Thomas Crow Chippendale examples. Philadelphia tall case clockmakers include Peter Stretch and John Wood.

Another marquee highlight is an exceptionally rare Charles Frederick Bell, Waynesboro, Pennsylvania painted redware spaniel. Stoneware highlights include a New York three-gallon merchants jug impressed Giles & Co., Cherry Valley, a Massachusetts two-gallon crock impressed Edmands & Co., and a Vermont two-gallon jug impressed J & E Norton, Bennington.

Decorative arts items of special interest include a 19th c. narwhal tusk; a ship log of the Mary of New Bedford, detailing an 1840-2 whaling voyage off the Australian coast of New Holland; a group of ten fabric sewing birds; and a set of twenty-five botanical engravings by Georg Ehret from Plantae Selectae, Nuremberg, 1750-1773.

On the evening before the sale, Tuesday, January 13, from 4:00 – 7:00 p.m., Pook & Pook will host an extended evening exhibition and special reception celebrating the publication of American Insights 2025, a comprehensive study of Pennsylvania German redware. Additional gallery exhibition hours and auction times can be found online at www.pookandpook.com. To contact the gallery with any questions dial (610) 269-4040 or email info@pookandpook.com.

Preview and bidding will be available in person and online at Pook & Pook. For details, visit www.pookandpook.com.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

2nd Choice Isn’t So Bad

The January 14–15–16, 2026 Americana sale at Pook & Pook Auction in Downingtown, Pennsylvania is overflowing with standout material, making it nearly impossible to choose favorites. Still, my Pick of the Week is Lot 57: a remarkable Berks County, Pennsylvania painted pine dower chest, dated 1794 and inscribed Margaretha __.

This exceptional chest retains its original decoration, featuring vibrant potted tulips on ivory panels with a rich blue surround and distinctive heart corners. Measuring 24″ high by 47 1/2″ wide, it carries an impressive provenance that includes the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Ronald Pook Antiques; a private Pennsylvania collection; Olde Hope Antiques; David A. Schorsch (1996); and the Collection of the late Grant H. Griswold.

The combination of color and design is simply outstanding. Every hallmark of classic Pennsylvania Germanic decoration is present—hearts, tulips, and checkerboard arched astragal panels—beautifully unified by matching flower pots that pull the entire composition together.

Having handled hundreds, if not thousands, of Pennsylvania blanket chests over the years, I can confidently say this sale includes two of my all-time favorites. Remarkably, this chest is my second choice. Be sure to check back next week when I reveal my number one example from this extraordinary auction.

by: Jamie Shearer

That’s Two Demeritts! Two!

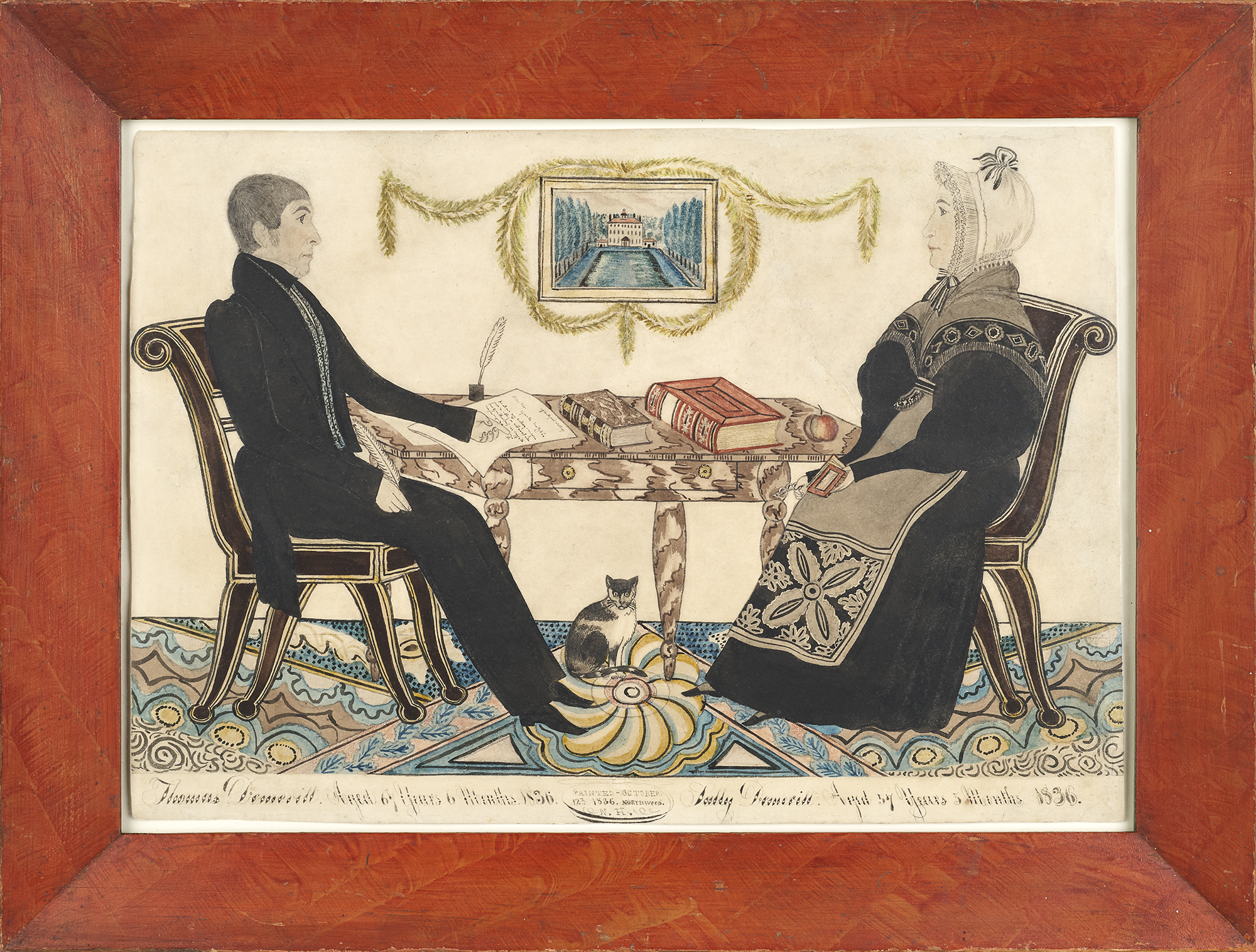

My Pick of the Week for the upcoming January 14–15–16, 2026 Americana Sale at Pook & Pook Auction in Downingtown, Pennsylvania, is a superb ink and watercolor double portrait by Joseph H. Davis (American, 1811–1865).

This finely rendered 1836 portrait depicts Thomas and Sally Demeritt of Northwood, New Hampshire, and exemplifies Davis’s distinctive, delicately detailed style. Measuring 10″ x 14″ (frame: 13 1/2″ x 17 1/2″), the work is an exceptional example of his ability to capture both likeness and character through spare yet elegant composition.

This painting is among Davis’s most thoroughly documented works, having been featured in multiple significant publications and exhibitions, including:

- The Magazine Antiques, October 1943 (Frank O. Spinney, “Joseph H. Davis, New Hampshire Artist of the 1830s,” no. B-6)

- Three New England Watercolor Painters, The Art Institute of Chicago exhibition catalog, 1974, no. 25

- The Magazine Antiques, September 1982 (Susan Klein et al., “Living with Antiques,” p. 512, fig. 1)

- The Clarion, Museum of American Folk Art, Summer 1989 (Arthur and Sybil Kern, “Joseph H. Davis: Identity Established,” p. 49)

Its distinguished provenance further underscores its importance, having passed through notable collections, including those of Mrs. Albert Boni, Betty Sterling (Randolph, Vermont), Ralph Esmerian (New York), David A. Schorsch, Inc. (Greenwich, Connecticut), Barry Cohen (New York), and again David A. Schorsch (1994).

A remarkable example of Davis’s artistry, this portrait is a standout offering in an already exceptional sale.

by: Jamie Shearer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_H._Davis_(painter)

Randerson Kills Prickett

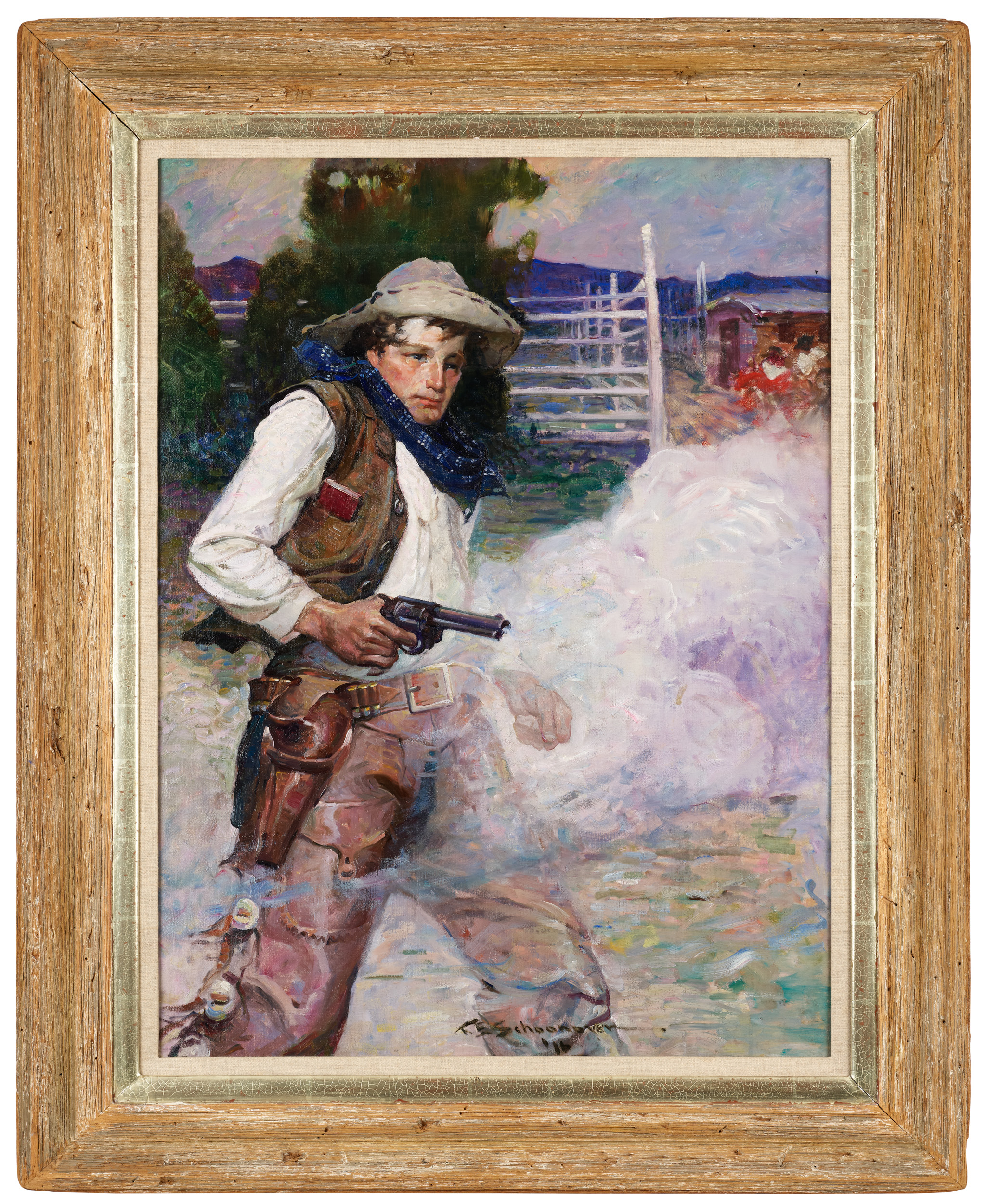

Lot 428, the oil on canvas Randerson Kills Prickett, and the lot gracing the cover of our October 2025 Americana catalog, is not only one of the finest paintings of an Old West gunslinger created, it is also one of the finest works to come out of the Brandywine School of illustration artists.

Frank Earle Schoonover (b. 1877, Oxford, New Jersey) studied illustration under Howard Pyle at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia. It was the Golden Age of Illustration, when artists worked closely with authors to create powerful visual storytelling to enhance books and commercial projects. In 1900, Pyle moved his program to his studio in Wilmington, Delaware, and Schoonover moved with him. Schoonover’s new studio was in a building shared by fellow artists N.C. Wyeth, Thorton Oakley, and Harvey Dunn.[1] Pyle taught his students to “live their work”, and to explore American history and culture to fuel their imagination. Frank Schoonover sought to capture the action and adventure of the Western frontier in America and Canada. He painted strong characters: Native Americans, cowboys, trappers, and explorers. “I never painted a weakling,” proclaimed Schoonover.[2] He excelled in portraying action, capturing the thrill and the movement of a scene. Cortlandt Schoonover describes his father as “above all, an artist of action.”[3]

In 1905, Schoonover embarked on a lengthy research trip to Denver, Colorado and Butte, Montana on assignment for McClure’s magazine. In Butte, “Schoonover also made the acquaintance of Rex Randerson, a local sheriff, who owned a picturesque though bony horse.”[4] Charles Alden Seltzer “used this character in a story based largely on Schoonover’s observations.”[5] The book, The Range Boss, was published in 1916. The story revolves around the character Rex Randerson, a range boss who helps new owner Ruth Harkness manage her ranch. It is a frontier tale full of bravery and action, gunslinging and cattle rustlers, in which the hero, in the end, gets the girl.

This painting shows range boss Rex Randerson shooting a cattle rustler named Prickett, and was captioned “The twilight was split by a red streak.”[6] It is one of several notable illustrations created for the book. (The most famous, Randerson On Patches, was reworked in 1926 into an iconic poster for the Colt Firearms Company.[7])

The painting Randerson Kills Prickett is a Frank Schoonover masterwork. It captures the moment Randerson fires his revolver. Captured in loose, impressionistic brushstrokes, his right arm and shoulder recoil from the shot. His stance is solid, stabilized by his forward leg and left hand, which is clenched into a fist and exquisitely outlined behind a veil of gun smoke. The gun smoke is a thing of beauty, a cloud of shimmering color. (Schoonover painted in the winters in the Poconos, in Bushkill, Pennsylvania, with Pennsylvania Impressionist Edward Redfield, who taught him to mix a bit of vermilion into white forms such as snow.[8]) The light, color, and action combine into a painting at the top of Schoonover’s oeuvre. Visible in the upper right is Schoonover’s unwritten signature, the touch of “Schoonover Red”, a splash of cadmium red added to heighten the drama and intensity of a scene.[9]

Please join us for our Americana auction October 1-3, and for our preview, September 27, 29, and 30, to see this painting, part of the Randy Anderson Collection of over twenty works from fellow members of the Brandywine School, including Gayle Porter Hoskins, Stanley Massey Arthurs, N.C. Wyeth, and others.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

[1] Schoonover, Cortlandt. Frank Schoonover. Illustrator of the North American Frontier. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1976.

[2] Schoonover, Cortlandt. Frank Schoonover, p. 13.

[3] Schoonover, Cortlandt. Frank Schoonover, p. 13.

[4] Schoonover, Cortlandt. Frank Schoonover, pp. 23, 24.

[5] Schoonover, Cortlandt. Frank Schoonover, pp. 24.

[6] Schoonover, John. Louise Schoonover Smith with LeeAnn Dean. Frank E. Schoonover Catalogue Raisonne. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2009. No. 726.

[7] Schoonover, John. Catalogue Raisonne, Nos. 733 and 1419.

[8] Schoonover, Cortlandt. Frank Schoonover, p.39.

[9] Schoonover, Cortlandt, Frank Schoonover, p. 39.

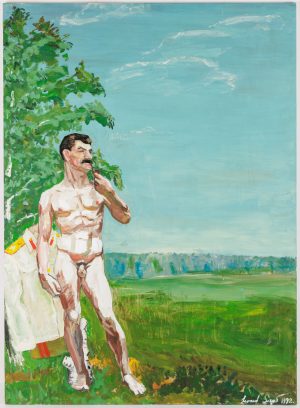

Sokov & Stalin

Vladimir Putin is attempting to revive the legacy of Stalin as a wartime leader. He has unveiled more than one hundred new statues of the brutal dictator during his twenty-five-year reign, the most recent in a Moscow metro station. The rehabilitation of Stalin legitimizes Putin’s authoritarian regime and his foreign policy. In this light, the work of Leonid Sokov continues to be as relevant as ever. Whether critiquing Stalin, the Soviet regime, Western consumerism, or the Russian reaction to the demise of the Soviet Union, Sokov’s art cuts to the matters of cultural expression and values.

Putin’s new statues depict Stalin as a father figure and strong leader, handsome, friendly, and pragmatic. Stalin, from his assumption of the office of General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1922 until his death in 1953, required all portraits of him to be approved by the State. This effectively controlled Stalin’s image, due to the abolition of private trade, the State was also the only consumer of art. The Soviet authorities required that Stalin be made taller, and better-looking. Sokov’s images of Stalin hew closer to reality and simultaneously expose other facets of the hypocrisy and authoritarianism of his deeply contested legacy.

Lot 240 Stalin/David Underbirch parodies the approved images of Stalin, and is not too far from how he is depicted (only clothed) in his new statue in Moscow’s Taganskaya metro station. The artistic achievements of the Renaissance were a far cry from the repression of artistic expression in Stalinist Russia. Stalin imposed the artistic style Socialist Realism, in which art had to serve as propaganda promoting communism and the Soviet state.

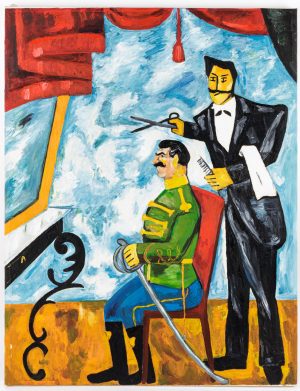

Lot 304 M. Larianov’s Paint and Stalin’s Head shows a bougie Stalin at the barber’s. Stalin disliked outward displays of wealth, and his mythology portrays him as an ascetic, but he was hugely wealthy, with unlimited access to the advantages of his office, all provided for him by the State. He lived a more lavish lifestyle than anyone in the Soviet Union.

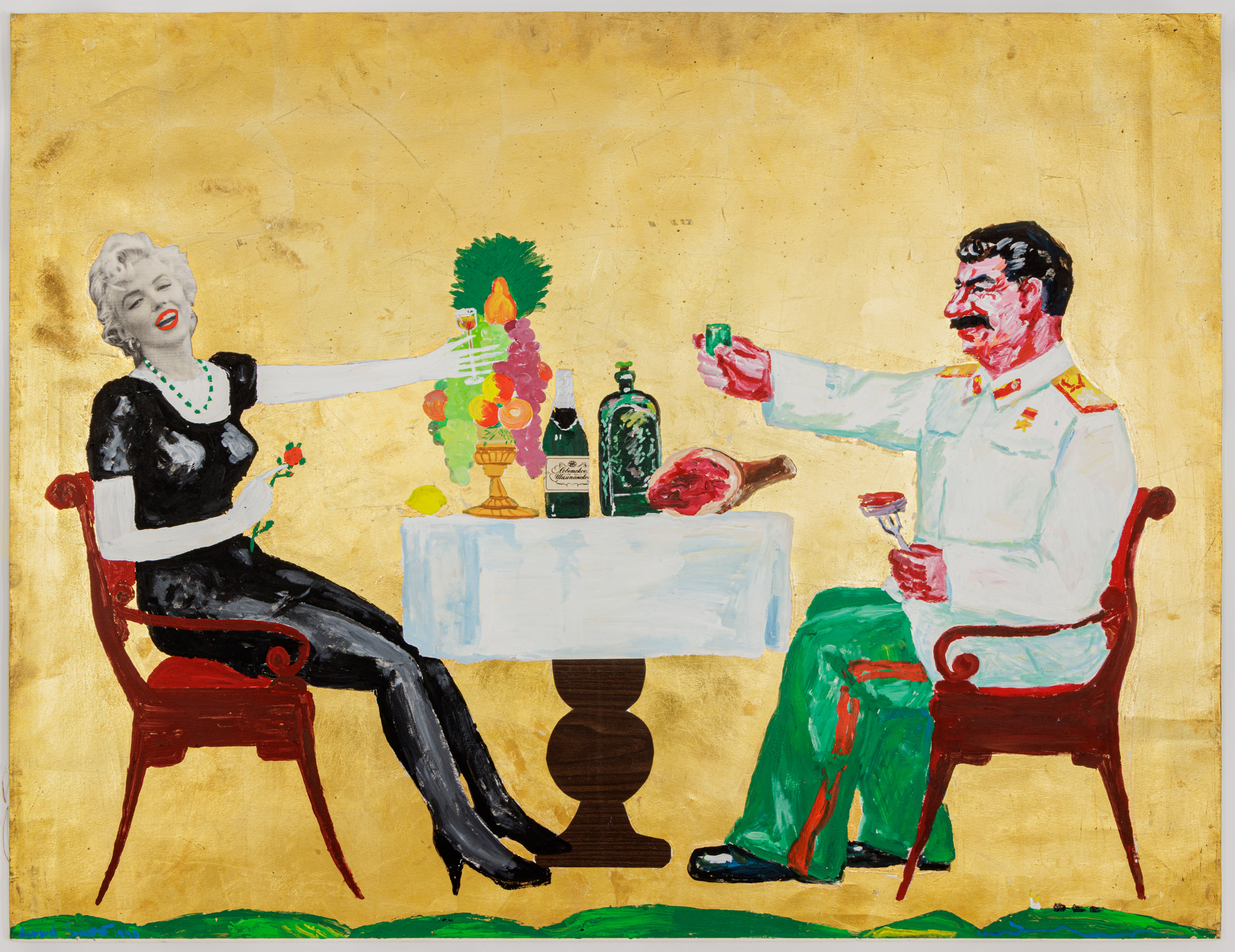

Lot 220 Stalin and Marilyn (Lovebirds) is a favorite theme, Stalin lustfully groping for Marilyn Monroe, who is symbolic of everything Stalin professed to despise.

Lot 164 Stalin and Marilyn At The Table is a scene in which Marilyn Monroe (representing the U.S.A.) flirts across the table with an overindulging Stalin. According to Andrei Kovalev, the mischievous Sokov “once expressed the hope that a hundred years from now no one would be able to recall if Stalin and Monroe had ever actually met.”

Lot 167 Ermolaeva With Chair Of Leonid Sokov depicts the brilliant avante garde artist Vera Ermolaeva. Ermolaeva, an “anti-Soviet element”, was executed by a firing squad in 1937, after several years of imprisonment in gulag camps, a victim of Stalin’s Great Terror.

Sokov’s artworks are not just a record of a moment in time, but a lasting commentary on Soviet repression, Russian nationalism, Western consumerism, and the battle for self-determination and the soul of the Russian people. Pook & Pook is honored to present one of the largest collections of his works ever to be exhibited or auctioned. Please join us to view these and many other important artworks in person Monday and Tuesday, July 14th and 15th, and online for bidding July 16th.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

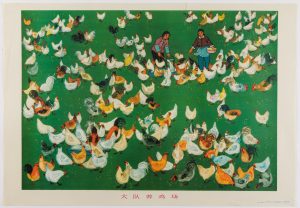

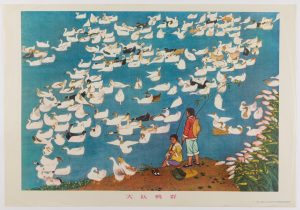

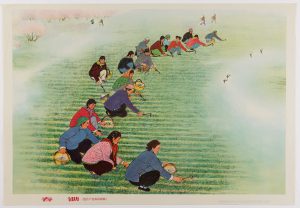

Cultural Revolution

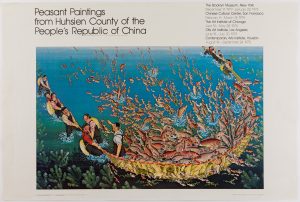

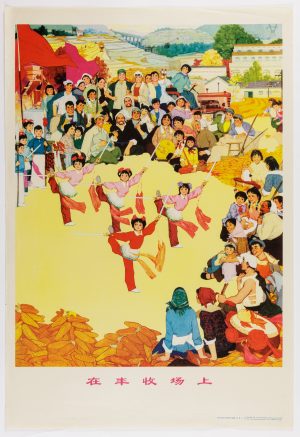

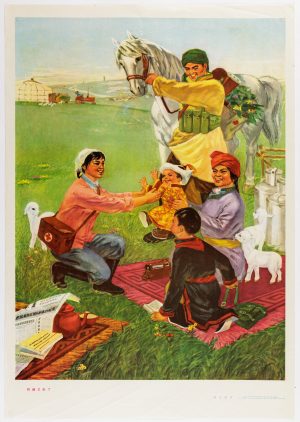

Lot 473 is a group of colorful, joyous scenes of rural Chinese farm life in the 1970’s. Created as Maoist propaganda posters, there is more to these works than meets the eye. My particular favorite is On-the-spot meeting of the swine industry, which shows workers gathered in a circle with cups of tea, bordered by animated pigs and piglets. Looking at this tea party, questions arise—such as why is one worker seated behind a big desk, and why are people taking notes?

One aspect of Mao’s Great Leap Forward and the accompanying Down to the Countryside Movement was the purge of intellectuals from institutions and their re-education and re-alignment with the working class through manual labor in rural areas. More than a few workers on this state-run pig farm were probably artists and intellectuals. The tea party is a farm meeting, which was a mandatory and serious event. Mutual criticism and self-criticism were regular features of the meetings, the purpose of which was the enforcement of ideology and social control. Workers were forced to confess their perceived mistakes and missteps, particularly any bourgeois ideas, and were denounced by others. Communist economies are centrally planned and controlled by the State, which determines how many sausages will be produced and who will eat them. The pig farm collective had targets set by the government which might not have reflected reality but were mandatory. The agricultural disruption of the Great Leap Forward created rural food shortages which persisted throughout the 1970s, making sausages scarce.

The artwork of these posters is another product of the Cultural Revolution. They are Huxian Peasant Paintings. Peasants were trained by artists and the CCP to create Party-approved propaganda artworks. The scenes are rich and colorful folk art depictions of good communists and productive workers. The paintings were distributed widely as posters, transmitting ideology to a semi-literate or illiterate rural population. Ironically, some of the pictured farm workers may have been artists who were not inclined to paint the joys of the Maoist purges.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Press Release – Fine Art from an East Coast Educational Institution

Pook & Pook Presents a Rare Opportunity to Acquire Exceptional Works of Modern and Post-war Art in Upcoming Auction

Downingtown, PA – Pook & Pook is excited to announce an exclusive online event featuring modern art and prints. This auction will offer 20th century pieces including iconic examples of surrealism, pop art, op art, and kinetic art all deaccessioned from a distinguished East Coast educational institution.

The auction will take place online on PookLive, Bidsquare, and Invaluable, beginning at 9 AM on Wednesday, July 16, 2025. Interested collectors can preview the entire collection of over 500 lots in person during a gallery exhibition held at Pook & Pook’s Downingtown location, on July 14th and 15th from 10 AM to 4 PM.

Highlights of the Auction:

Romare Bearden – Master of Collage

One of the most important African American artists of the 20th century is represented by eight lots of his iconic works.

Bearden was a renowned artist best known for his innovative collage work and contributions to the Harlem Renaissance and modern art. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, and raised in Harlem, Bearden’s art was deeply influenced by African American culture, music—especially jazz and blues—and the social and political issues of his time.

Initially trained as a painter, Bearden developed a unique collage technique in the 1960s, layering images from magazines, newspapers, and painted paper to create powerful, vibrant scenes. His work often depicted everyday life in Black communities, blending realism with abstraction and symbolism. Notable themes in his art include family, religion, music, and the Black experience in both the rural South and urban North.

Leonid Sokov – A Spotlight on Russian Art

A major highlight of the auction is the presence of over one hundred original works by Leonid Sokov, one of Russia’s leading contemporary artists. Sokov’s works often combine elements of Russian folk culture with social commentary, creating pieces that challenge both artistic and political boundaries.

Sokov was born in 1941 in Moscow and became a significant figure in the underground art movement in the Soviet Union. His works often juxtapose absurdity and humor, utilizing familiar Soviet symbols and combining them with contemporary visual language. One of Sokov’s remarkable contributions to the art world is his ability to subvert socialist realism through surreal and ironic imagery. A particularly striking work in this auction measures a staggering 93 inches long, an immense example of his bold style.

Mikhail Turovsky – Master of Ukrainian Expressionism

This auction also includes several exceptional oil-on-canvas works by Ukrainian artist Mikhail Turovsky, whose emotive and striking paintings have captivated collectors worldwide.

Turovsky, born in 1949 in Ukraine, is a well-known figure in contemporary Ukrainian art. His works are characterized by expressive color palettes and abstract forms, blending traditional techniques with modern interpretations of the human experience. Turovsky’s art captures the poignant tension between inner emotion and outer reality, making his paintings both timeless and resonant.

Lydia Dona’s Mind-Bending Conceptual Works

Israeli artist Lydia Dona will also make her mark in the auction with two major conceptual works: Plutonian Enclosures and Let Me Know About the Fourth Dimension at the Border of Knowledge. Both pieces reflect her fascination with the intersection of science, philosophy, and art, exploring the boundaries of human perception. There are four works total set to cross the virtual auction block.

A Unique Dibond Sculpture by Frederick Eversley

Of particular interest is a Dibond/reflective silver polyester film, pigment, and ink disc sculpture by Frederick Eversley, a key figure in the West Coast Light and Space movement. His stunning use of reflective surfaces and geometrical forms offers a dynamic interplay of light and color, making it a must-see for collectors of cutting-edge contemporary art.

Notably, this auction also features a collection of Chinese Communist propaganda posters that offer a fascinating glimpse into a politically charged era, as well as artist exhibition posters that document pivotal moments in art history.

Auction Details:

- Date & Time:

- Wednesday, July 16, 2025, 9 AM (EST)

- Location: Online bidding at PookLive, Bidsquare, and Invaluable

- Gallery Exhibition: July 14th and 15th, 2025, from 10 AM to 4 PM at Pook & Pook, 463 East Lancaster Avenue, Downingtown, PA

All bidding for this auction is online only. For information, condition reports, or additional images on the lots in this auction, please email conditions@pookandpook.com. For details on this auction or any upcoming events, please visit www.pookandpook.com.

About Pook & Pook:

Pook & Pook has established itself as one of the premier auction houses for fine art, antiques, and collectibles. Known for its exceptional customer service and global reach, Pook & Pook is committed to offering rare and important works that appeal to collectors, curators, and art enthusiasts alike.

Contact:

Pook & Pook, Inc.

463 East Lancaster Avenue

Downingtown, PA 19335

Phone: 610-269-4040

Email: info@pookandpook.com

Website: www.pookandpook.com

Press Release – May 1st & 2nd Americana Auction

DOWNINGTOWN, PENNSYLVANIA — Pook & Pook presents the annual Spring Americana sale, May 1st and 2nd, 2025. The sale will be held live, with bidding in-person or online at PookLive, and also by telephone, or absentee bid. All items are illustrated in our award-winning full-color catalogue, available for purchase on Pook & Pook’s website. Works of art, folk art, furniture, and silver are accompanied by particularly strong militaria and Native American categories.

Fine art highlights include four works by Sir Alfred Munnings: equine portrait Leader, A Bay Horse, 1905 (estimate $20,000-30,000); landscape Winter at Flatford Mill, portrait of red setter Lark III; and a cloud study landscape. American artists include Charles Willson Peale, William Aiken Walker, Willem de Kooning, Frank Earle Schoonover, Eric Sloane, Hattie Klapp Brunner, and Violet Oakley.

A Chester County Pennsylvania Chippendale walnut secretary (estimate $5,000-8,000) is attributed to the shop of Jacob Brown (Nottingham Township, b. 1724). Similar clock cases are known with works by Benjamin Chandlee Jr., one with a record of descent in the family of the cabinetmaker. Other Pennsylvania furniture highlights are a Lancaster walnut schrank, a narrow walnut corner cupboard, and a vibrant painted blanket chest. New England highlights are a Connecticut Queen Anne cherry high chest and a Boston Queen Anne walnut dressing table.

Clocks and instruments by the Chandlee family include a rare brass surveyor’s compass by Goldsmith Chandlee (Winchester, Virginia 1751-1821) (estimate $5,000-8,000), and a walnut tall case clock by Ellis and Isaac Chandlee (Chester County, Pennsylvania, fl.1792-1804).

A rare tall case clock by New Jersey’s earliest clockmaker Isaac Pearson (Burlington 1685-1749) is related to an example in the Winterthur collection (estimate $3,000-5,000).

Decorative arts highlights include two scarce Warne & Letts (South Amboy, New Jersey) stoneware crocks, and thirteen lots of D.P. Shenfelder (Reading, Pennsylvania) stoneware, with a rare marked piece. A Tiffany Studios bronze picture frame features abalone shell inlay. Another standout is an elaborate 19th c. Pennsylvania wrought iron spatula. Silver includes four lots of trays and tableware by Georg Jensen, and several S.Kirk & Son Baltimore repousse ewers. A fine collection of quilts features an exceptional Pennsylvania Whigs Defeat patchwork quilt.

The militaria and firearms offerings are extensive, incorporating not only the history of America, but countries afar. Civil War era items include two Robert E. Lee signed letters, paintings by William Frye and Alonzo Chappel, and a 32-star American linen flag which, by family tradition, was taken to Gettysburg during Abraham Lincoln’s visit in 1863 by Alice Dome’s grandfather. The flag then passed down in the Dome family of Arendtsville, Adams County, Pennsylvania. Firearms include a Sharps model 1874 Business rifle, and a U.S. Navy Colt model 1911 semi-automatic pistol. A collection from Piedmont, Charles Town, West Virginia, features many highlights, the most important of which symbolizes Poland’s contribution to the American Revolutionary War. A rare Polish silver-mounted Hussar’s sabre and scabbard, ca. 1770, possibly belonged to Brigadier General Casimir Pulaski or Colonel Tadeusz Koscuiszko. Other Polish 16th – 19th c. weaponry includes a fine Rochus Daiczer Polish flintlock pistol, highly engraved and gold-damascened; a Polish Hussar Nadziak war hammer, ca. late 16th – early 17th c.; and a silver inlaid Polish karabela sabre and scabbard, ca. 1700. American highlights from the Piedmont collection are a Nashville Plow Works Confederate Civil War sword and scabbard, and a Jacob Hurd (Boston, 1703-1758) silver mounted small sword.

Native American antiques include fine works from two collections. Of the many weavings, highlights include a Navajo Third Phase woman’s blanket, ca. 1880; two Navajo Third Phase Germantown chief’s wearing blankets, ca. 1880; and a Navajo Second Phase variation wearing blanket, late 19th c. Antique pottery includes a fine Acoma Pueblo Indian pottery olla, ca. 1900. Basket works include an Apache coiled basketry tray, and an Apache coiled basketry bowl, both ca. 1900. Another highlight is a Micmac Indian porcupine quill, birch bark, and walnut chair, 19th c.

For more information please visit www.pookandpook.com or call (610) 269-4040. Gallery exhibition hours are posted online. To consign with Pook & Pook, please email photographs to info@pookandpook.com.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Up to snuff

Snuffboxes came into wide circulation with the increasing importance of tobacco use in the West. Tobacco was first prized as a medicine when first imported from the New World in the late 16th century. Europeans delighted in the effects of nicotine from the exotic tobacco plant, and the demand for tobacco grew. Snuff did not become popular in France until after the 1715 death of King Louis XIV, who disapproved of tobacco. By the 1730s, however, snuff was firmly at the center of fashionable French customs, and an important social aspect of the court.

Eighteenth century Paris produced the finest luxury goods in Europe. The entire Parisian economy was based on small, skilled artisan workshops. The personal goods produced included snuffboxes, miniature masterpieces that became as coveted as tobacco itself. Snuffboxes were the height of fashion, with the most elegant made of gold, often set with diamonds, enamels, and other precious materials– the more exotic, the better. A Parisian gold snuffbox was among the most expensive and desirable status symbols of the day. They were frequently presented as royal gifts to courtiers and ambassadors, and many were given for service to the crown.

Snuffboxes and snuff were important social indicators. Taking snuff evolved into elegant solitary acts, in which was displayed as much style and grace as possible, and group activities, where “the act of handling the box and offering snuff evolved into a secret code, the ‘language of the tabatiere.’”(Victoria & Albert Museum, Gold boxes) Pity the poor lover of Carl Alexander von Lothringen, who had to interpret the signal recorded in his diary that “taking snuff, and then pretending to flick traces of it from his coat or fur tippet, was his way of asking his beloved whether she would attend a ball.” (V&A, Gold boxes) The gold boxes were also given on occasions of marriage and in friendship amongst powerful and influential people, with many examples known to have been owned by historically important 18th c. figures.

This Nicolas Marguerit oval snuffbox, lot 8044, is an example of the pre-eminence of Parisian goldsmiths. Decorated in three colors of gold, the lid is engraved with a fine guilloche wave pattern surrounded by a border of symmetrical leaf swags. The side of the box with four panels of the same pattern below a frieze of stylized laurel leaves and flowers. The side panels are divided by vertical ribbon-topped columns with neoclassical motifs such as a torch and quiver, and a lute and horn, as well as pastoral motifs such as a basket and crook, and a bagpipe, staff, and hat. It is marked inside the lid, inside the base, and on the rim for Nicolas Marguerit (fl. 1763-1790), Paris. Marguerit was an apprentice until 1751 and earned his Master’s status on January 17, 1763, endorsed by Germain Chaye. He was active until 1790, recorded at Carrefour des Trois Maries in 1774, rue de Montmorency in 1782, at Place de Trois Maries in 1783-87, and at rue Hillerin Bertin from 1788-1790. Gold snuffboxes by Nicolas Marguerit can be found in collections such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum Collection, Moscow.

A handwritten note kept inside the box reads: “This snuffbox was presented to J.H. Cochrane of Rochsoles by the Duchess of Hamilton. A letter from the Duchess to J.H.C. will be found in the Family Book referring to this. H.L.C.” It is not known exactly what the Cochrane Family Book reveals, crucially, whether this snuffbox was given in 1768, or purchased and presented to Cochrane at a later date, but we do know a little about the Duchess of Hamilton of the period, Elizabeth Gunning (1733-1790).

Elizabeth Gunning, Duchess of Hamilton, Gavin Hamilton, 1753. Photo credit: Scottish National Gallery.

Elizabeth Gunning was a real-life Cinderella story, an Anglo-Irish beauty born into relative obscurity. Elizabeth and her sister caused a sensation in 1750 when they were presented to the Court. Renowned for their beauty, their fame spread throughout London. Their lives became a whirl of grand balls and soirees. At a Valentine’s Ball at Bedford House in 1752 Elizabeth met James Hamilton, 6th Duke of Hamilton. James Hamilton was young and goodlooking, but dissolute, and full of bad ideas. They were married that night, at 12:30, at Mayfair Chapel where a marriage license was not required. Such was their haste, a bedcurtain ring had to serve as a wedding band. Horace Walpole chronicled their brief courtship. It is well worth a read.

From the Letters of Horace Walpole, 27 Feb, 1752: “I write this as a sort of letter of form on the occasion, for there is nothing worth telling you. The event that has made most noise since my last, is the extempore wedding of the youngest of the two Gunnings, who have made so vehement a noise. Lord Coventry, a grave young lord, of the remains of the patriot breed, has long dangled after the eldest, virtuously with regard to her virtue, not very honourably with regard to his own credit. About six weeks ago Duke Hamilton, the very reverse of the Earl, hot, debauched, extravagant, and equally damaged in his fortune and person, fell in love with the youngest at the masquerade, and determined to marry her in the spring. About a fortnight since, at an immense assembly at my Lord Chesterfield’s made to show the house, which is really magnificent, Duke Hamilton made violent love at one end of the room, while he was playing at pharaoh at the other end; that is, he saw neither the bank nor his own cards, which were of three hundred pounds each: he soon lost a thousand. I own I was so little a professor in love, that I thought all this parade looked ill for the poor girl, and could not conceive, if he was so much engaged with his mistress as to disregard such sums, why he played at all. However, two nights afterwards, being left alone with her while her mother and sister were at Bedford House, he found himself so impatient, that he sent for a parson. The doctor refused to perform the ceremony without license or ring: the Duke swore he would send for the Archbishop – at last they were married with a ring of the bed-curtain, at half an hour after twelve at night, at Mayfair chapel. The Scotch are enraged, the women mad that so much beauty has had its effect, and what is most silly, my Lord Coventry declares he now will marry the other.”

Elizabeth’s celebrity was such that she drew crowds of onlookers wherever she went. After the Duke died in 1758, she married John Campbell, the future of Argyll, and later was Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Charlotte. In 1776 she was made Baroness of Hamilton in her own right. While research into the Cochrane Family Book should reveal which Duchess of Hamilton presented this snuffbox with its bagpipe motif, a very probable first owner was the glamorous Elizabeth Gunning.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

From Grandma’s Closet to Modern Runways: Brooches are Back in Style

When you think of a brooch, what’s the first thing that comes to mind? Maybe your thoughts drift to “outdated” or “too fussy for my style.” It’s time to challenge those old notions because brooches are making a major comeback as one of the hottest trends of 2025. Sure, your grandma may have adored them, but there’s no reason why you can’t fall in love with them too. And here’s the exciting part—they’re no longer just for women! Brooches are crossing gender lines and becoming a must-have accessory for everyone. Don’t let the past hold you back; it’s time to embrace the brooch revolution.

The brooch is a piece of jewelry that transcends fleeting fashion trends, standing as a symbol of timeless elegance in an ever-evolving world of style. Dating back to the Bronze Age, brooches were not just ornamental but served a practical function, used to fasten clothing and keep garments in place. Over the centuries, this versatile accessory evolved into a striking statement piece, with intricate designs and dazzling embellishments that catch the eye and command attention. No wonder, then, that a beautiful brooch can make one feel truly special, as it embodies both history and personal expression, all while adding an undeniable touch of grace and refinement.

Madeleine Albright and Queen Elizabeth II stand out as two of the most prominent brooch wearers in modern history. Even Queen Victoria was known to wear a mourning brooch crafted from Prince Albert’s hair. In recent years, men have also embraced the charm of the brooch, incorporating them into their red carpet ensembles, as demonstrated at the 2025 Oscars. Robert Downey Jr., Cillian Murphy, Matthew McConaughey, Ryan Gosling, and numerous other male celebrities enhanced their formalwear with bold statement brooches on their lapels (https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/13/style/brooches-male-celebrities-oscars.html).

The timeless brooch is far more than a simple pin to adorn your jacket lapel; it’s a versatile accessory that can effortlessly transform your entire look. Use a brooch to cinch a waist that’s slightly too big, turning a loose-fitting garment into a flattering silhouette. Clip a brooch onto a headband to elevate your hairstyle, adding a dash of sophistication or whimsy, depending on the design. The possibilities are truly endless. With its bold presence and captivating beauty, there’s no need for a necklace or earrings—let the brooch be the star of the show, commanding attention and infusing your outfit with a sense of individuality and flair.

Where can you find these fashion must-haves? Check out Pook & Pook’s upcoming Coins and Jewelry Auction on March 26 and 27, 2025, where you’ll have the opportunity to view an exquisite selection of dozens of antique brooches that showcase the craftsmanship of bygone eras. For those with a taste for minimalism, Lot #8019 offers an elegant and understated yellow gold flower brooch by Tiffany & Co.—a perfect piece for those who appreciate subtle beauty. If you prefer to make a bolder statement, Lot #7870 is sure to capture attention: a stunning synthetic spinel, flanked by thirty-five sparkling round diamonds, all set in a luxurious 18K gold and platinum design. Whether your style leans toward the delicate or the dramatic, one thing is clear—the brooch continues to be a timeless and indispensable accessory that will never go out of fashion.

By Erika Lombardo

Lot 8019

Sources:

Southernliving.com “Your Grandmothers Favorite Accessory is 2025’s Most Stylish Comeback Trend” by Kaitlyn Yarborough, January 18, 2025.

Harpersbazaar.com “Brooches are Trending on the Runway” by Julie Tong, February 14, 2025.

Thefashionfold.com “Brooches are the 2025 Jewelry Trend to Instantly Elevate Your Look” February 9, 2025.

Newyorktimes.com “The Bro Brooch Sweeps Award Season” by Guy Trebay, March 13, 2025

A Touch of Mughal Magnificence

Lot 7875 is an antique Mughal gold and enamel bracelet, set with diamonds, emeralds, and natural and synthetic rubies. Dated to approximately 1880, this bracelet was purchased by its current owners from the Ganeshi Lall & Son Emporium in Agra, in 1956. In accompanying provenance, the bangle is documented as being acquired “from one of the families of ex-ruling Princes from Southern part of India.” It is an example of the exuberant, rich Mughal style. Crowned with enameled elephants with trunks intertwined, it is studded with gemstones and intricate enamel work.

Storied purveyors of Indian jewelry, Ganeshi Lall & Son was established in 1845. The company had stores in Agra, Calcutta, and Simla, a hill station where the British Raj went to escape the summer heat. In 1934 a Cairo store was established, directly across the street from the famous Shepheard’s Hotel. Hotel guests such as the Aga Khan, Theodore Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, Agatha Christie, and T.E. Lawrence, while relaxing on the patio, would undoubtedly notice the Ganeshi Lall & Son storefront opposite.

Patio of Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo, ca. 1940. Photo credit: Arts of Hindostan.

Travelers to the Taj Mahal in Agra also frequented the original Ganeshi Lall & Son emporium. Famous patrons included Prince Charles, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, Prime Ministers Nehru and Indira Gandhi, and Mick Jagger. Queen Mary was evidently also a loyal customer, as the company continued to receive Royal Warrants appointed in her name in the 1960’s and 70’s. Ganeshi Lall & Son also supplied jewelry and art to institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

India has long been a center of jewelry and gemstones. The Golconda region has been mined for diamonds for over 2,500 years. Until the 17th century, Golconda was the only source of diamonds in the world. Traders from Europe and Asia transported the diamonds far and wide. Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) documented the Roman imperial demand for Indian diamonds.

The sophistication and opulence of the Mughal court was renowned. Descendents of Tamerlane, the rulers of the Mughal period (1526-1858) were great patrons of the arts and expressed their power and individuality through their jewelry. Mughal jewelers had access to the world’s finest known diamonds, and also imported rubies from Burma and emeralds and sapphires from Ceylon. Sir Thomas Roe (1580-1644), English ambassador to the Mughal court, wrote to Charles I of the emperor Jahangir, “In jewells (which is one of his felicityes) hee is the treasury of the world.” (Treasury of the World: Jeweled Arts of India in the Age of the Mughals, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002)

The Mughal emperors brought Persian and Asian influences to India, including the art of enameling, known as Meenakari. India had a long-established tradition of Kundan jewelry, which involves the setting of gemstones directly into molten gold foil. Kundan techniques had been present in India since the 3rd century BCE, but flourished in the Mughal courts. The two techniques combined to produce jewelry such as this bracelet, a beautiful example of Mughal style.

By Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Pook & Pook’s Spring Coins & Jewelry Auction

Pook & Pook’s Coins & Jewelry Auction on March 26th & 27th, 2025 to Feature Hundreds of Rare Treasures from the Pennsylvania Treasury Department’s Bureau of Unclaimed Property

Downingtown, PA — Get ready for an extraordinary opportunity to own some of the finest coins and jewelry on the market at Pook & Pook’s upcoming Coins & Jewelry Auction on March 26th & 27th, 2025. This exciting event will be held exclusively online via PookLive and Bidsquare, featuring hundreds of rare and valuable items, many of which are coming directly from the vaults of the Pennsylvania Treasury Department’s Bureau of Unclaimed Property.

The gallery exhibition will take place on March 24th & 25th from 10 AM to 4 PM at Pook & Pook’s gallery in Downingtown, PA, where you can view all of these incredible pieces in person before bidding begins.

Pook & Pook is an exceptional auction house with a rich history. This auction is particularly special, as it includes a variety of fascinating items deaccessioned from the vault of the Pennsylvania Treasury Department’s Bureau of Unclaimed Property. These treasures were once held by the state, awaiting their rightful owners. However, after thorough due diligence on the part of the Treasury in seeking out those owners, a portion of these unclaimed items must periodically be offered at auction, providing bidders with the rare opportunity to acquire these exceptional pieces. Pook & Pook has had the distinguished honor of working with the state and assisting with this important process for the past decade.

Coins and jewelry are not only beautiful and collectible—they’re also wise investments. As precious metals like gold and silver fluctuate in value, owning rare coins and fine jewelry can be a hedge against inflation, making them a secure and potentially profitable asset for years to come. Rare coins, in particular, have historically shown strong appreciation in value, while high-quality jewelry made from platinum, gold, and diamonds remains an enduring symbol of prosperity and beauty. Whether you’re a seasoned collector or a first-time buyer, this auction offers a perfect opportunity to invest in items that will hold lasting value.

Jewelry Highlights

The jewelry selection is a dream for collectors, with extraordinary pieces from some of the most prestigious designers and jewelers. Notable highlights include:

- A Platinum Three-Stone Ring featuring a square natural emerald and diamonds, estimated at $2,000-3,000

- A Platinum Two-Stone Ring with a square ruby and diamonds, estimated at $3,000-4,000

- A stunning Platinum Cartier Brooch with five natural sapphires and over two dozen diamonds, estimated at $4,000-5,000

- 14K Clip-On Earrings with seventy-six tapered and straight baguette diamonds, estimated at $3,600-4,600

- An 18K Gold Musical Watch Fob, estimated at $1,000-1,200

- A beautifully crafted Nicolas Marguerit Gold Snuff Box from the 18th century, estimated at $4,000-5,000

- A rare 14K Gold Knights Templar Presentation Medal with engraving, estimated at $5,000-6,000

Additionally, items by renowned brands such as Cartier, Tiffany, Omega, Gucci, Bulova, and Michael Kors will also be available. Don’t miss the chance to bid on exquisite wristwatches, pocket watches, and diamonds from Old European and Old Mine cuts, as well as natural sapphires, emeralds, rubies, and more.

Coin Highlights

For coin collectors, this auction offers an impressive selection of both American and international rarities, including:

- Liberty Head $20 Gold Coins, Buffalo Nickels, Walking Liberty Half Dollars, and Morgan Silver Dollars

- Over a dozen Gaudens $20 Gold Coins and a rare Indian Princess Gold Dollar

- A striking Australia Dragon & Tiger 2 ozt Fine Gold Coin, estimated at $4,000-4,400

- Austria 100 Corona Gold Coins, estimated at $2,000-2,200

- A fine Switzerland Helvetia Gold Proof Set, estimated at $3,400-3,600

- Two lots of ancient Roman Follis Coins, offering a glimpse into the distant past

- An Engelhard 100 ozt Fine Silver Bar, estimated at $2,200-2,400

The collection spans not only American coins, but also pieces from around the world, including Canada, Australia, Russia, Great Britain, France, Germany, Mexico, South Africa, and more.

Coin collecting has been a respected pursuit for centuries, referred to in Renaissance times as “the hobby of kings.” From rare gold coins to historic silver pieces, numismatics offers a fascinating way to connect with the past while building an investment portfolio. As rare coins become increasingly scarce, collectors and investors continue to seek out unique and valuable pieces like those featured in this auction.

For more information about this exciting auction, including full auction details and to view the catalog, visit www.pookandpook.com or call (610) 269-4040. Don’t miss out on this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to own some of the most unique sought-after coins and jewelry in the market!

Consign with Pook & Pook

If you have valuable coins or jewelry you’d like to consign, Pook & Pook is now accepting consignments for the October 29th Coins & Jewelry Auction. Simply email photographs of your items to info@pookandpook.com to get started.

About Pook & Pook, Inc.

Pook & Pook, Inc. is a premier auction house specializing in fine art, antiques, collectibles, and jewelry. Known for its exceptional service and expertise, Pook & Pook offers online bidding for clients worldwide through PookLive and Bidsquare. With a commitment to providing a wide array of rare and valuable items, Pook & Pook remains a trusted leader in the auction world.

The Benefits of Deaccessioning Unused Items in Museums: A Smart Strategy for Financial Sustainability

In the world of museums, the careful management of collections is essential for maintaining their cultural and educational missions. However, as collections grow over time, there are often items that become outdated, irrelevant, or simply take up valuable storage space. Deaccessioning—removing an item from the museum’s permanent collection—is a vital process that many museums are increasingly considering. This practice, while controversial at times, offers numerous benefits to museums, especially in the context of raising funds, reducing expenditures, and sustaining long-term operations.

- Raising Funds to Further the Museum’s Mission

One of the most immediate and powerful benefits of deaccessioning is the potential to raise funds that can be reinvested into the museum’s mission. Selling unused or unnecessary objects can generate significant revenue that allows museums to fund educational programs, preserve and care for their remaining collections, purchase relevant items for exhibition, or invest in much-needed renovations and expansions.

Museums that are struggling with financial constraints can often turn to deaccessioning as a way to bolster their financial health. Funds from selling items can support essential operational costs, such as staff salaries, acquisitions of new works, and special exhibits that attract visitors and raise awareness of the museum’s value to the community.

- Decreased Expenditures on Storage

Museums face significant costs related to the storage and maintenance of their collections. As collections expand, the need for storage space grows, sometimes requiring costly off-site warehouses, climate control systems, and specialized storage materials. These expenses can quickly add up, diverting resources away from more pressing priorities.

By deaccessioning unused or irrelevant items, museums can downsize their storage requirements and, in turn, reduce expenditures. Fewer items mean fewer resources spent on preserving, storing, and managing objects that no longer serve the museum’s mission. It also creates a more organized and manageable collection that can be more effectively cared for, with limited staff and financial resources.

- Addressing the Rising Costs of Maintaining a Museum

The rising costs of running a museum—due to inflation, increasing insurance premiums, and a general increase in operational expenses—pose challenges for many institutions. For smaller museums or those facing decreased attendance, deaccessioning offers a practical solution to offset these rising costs.

Museum maintenance, including cleaning, climate control, and security, becomes increasingly expensive as collections grow. By divesting of non-essential objects, museums can free up space and reduce the ongoing costs associated with maintaining these items, ultimately allowing them to focus resources on the more critical elements of their collection.

- Managing Decreased Attendance and Donations

Many museums are also grappling with decreased attendance, which translates into lower revenues from ticket sales, special programs, and merchandise. This decline in visitors can also affect the volume of new donations. As public interest wanes, some museums face an overabundance of donated items that may not fit with their collection strategy or mission.

Deaccessioning allows museums to streamline their collections and ensure that the items they hold remain relevant to their audience and objectives. It also gives museums the ability to recapture space that may be used for more engaging exhibits or visitor-focused areas, boosting the overall visitor experience. Reducing the clutter of donated items helps curators focus on the most important pieces, which can drive further engagement and public interest.

- The Power of Auctions for Quick and Efficient Sales

A popular and efficient way for museums to deaccession and sell unwanted items is through auctions. Auction houses are well-equipped to handle all aspects of the deaccessioning process, from advertising and marketing to photographing and listing items for sale. This method offers a quick turnaround and minimizes the administrative burden on museum staff, allowing them to focus on other important tasks.

Auctions also have the advantage of bringing in specialized audiences interested in specific types of objects, such as collectors or enthusiasts who are looking for unique pieces. Auctions handle the logistics of insuring items, photographing them, writing descriptions, and collecting payments, which would otherwise require significant time and effort from the museum’s staff.

Moreover, because auctions often attract competitive bids, museums can sell items for higher-than-expected prices. This can generate a greater revenue than other methods of selling, benefiting the museum’s financial standing and ensuring that the object is placed in the hands of someone who truly values it.

- Ethical and Transparent Deaccessioning Practices

While deaccessioning is a valuable tool for museums, it must be done with great care and consideration. Museums must adhere to ethical guidelines and be transparent about the process. For instance, the proceeds from deaccessioning should generally be used for purposes directly related to the museum’s mission, such as the acquisition of new objects, educational programs, or conservation efforts.

Additionally, museum staff and trustees must ensure that deaccessioning is not used solely as a financial strategy but as part of a well-considered plan to improve the overall collection and the museum’s sustainability. Clear policies and communication with stakeholders, including donors and patrons, are essential for maintaining trust and credibility in the community.

Conclusion

Deaccessioning offers museums a strategic way to generate funds, reduce storage costs, and manage the rising financial pressures they face. Selling unused or irrelevant items—through the efficient and streamlined process of auctions—can help museums maintain their operations and improve the visitor experience, ultimately allowing them to continue their valuable work in education, culture, and preservation. By embracing deaccessioning as a tool for financial sustainability, museums can ensure that their collections remain meaningful, focused, and aligned with their long-term goals, all while securing the resources necessary to thrive in an increasingly challenging environment.

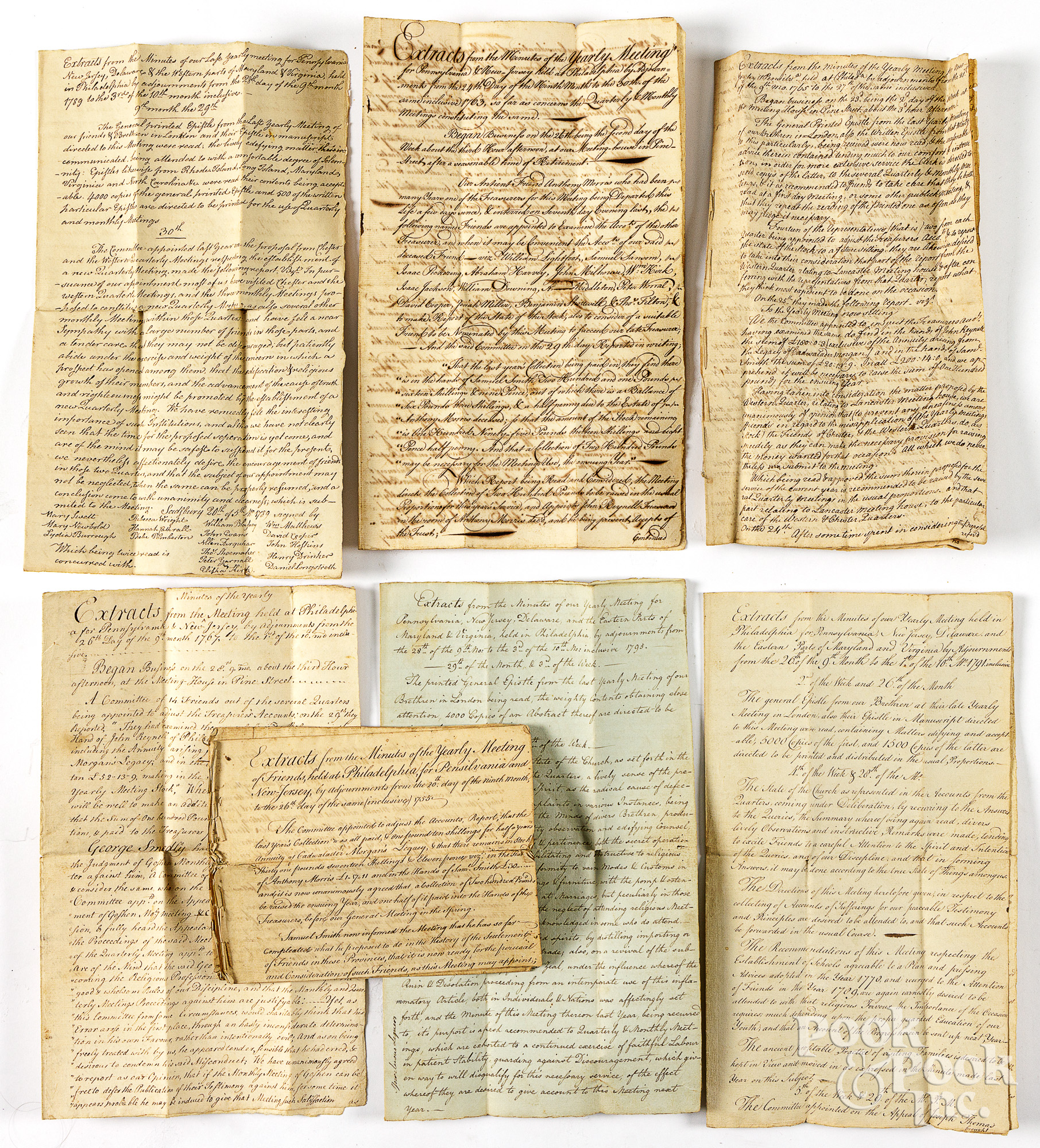

Brotherly Love

“We Salute you in Brotherly Love” begins a 1745 Epistle from the Quaker yearly Meeting in London. Handwritten by John Gurney, it reads like a sermon, exhorting the Friends to live in the ways of Holiness and Truth. It is evident in dozens of Epistles recorded over the next one hundred years that the Quakers of Philadelphia and the surrounding areas attempted to do exactly that. Divided into ten lots, #5939-5948, this fascinating collection of meeting notes charts the lives, challenges, and hopes of a Who’s Who of 18th and early 19th century Philadelphia area Quakers.

Quaker children dwelling in outlying areas were at risk, being “placed in with those not in membership with us” for schooling and being unduly influenced by “Evil Examples”. To address this issue, in 1794 plans were realized “relating to the Establishment of a Boarding School… in some suitable place or places in the Country… the use and benefit whereof, to be confined to the Children of Friends,” with “the amount of about five thousand pounds to be applied to the promoting of such an Establishment.” The committee assigned to plan the school, set rules and regulations, allocate money to purchase land and erect buildings would report yearly progress, and construct what is almost certainly the Westtown School. The Extracts trace their progress. In 1798, “the necessary buildings are mostly erected, and nearly finished, so as to be ready to receive children as soon as suitable persons may be engaged to instruct them, and superintend the economy of the house, etc.” In 1799, the boarding school reported admission of sixty girls and seventy-three boys.

The Quaker desire for peaceful coexistence led to concern for the plight of the “Distressed Inhabitants of the Wilderness”, and the call for a Native American school. A 1795 Extract reported “… there are loud calls for our benevolence & charitable exertions to promote amongst them the principles of Agriculture and useful mechanic employments” and a call to raise funds towards that purpose, a school. A later 1827 report from “The Committee, on whom is devolved the concern for the gradual civilization of the Indian natives” informs the Friends that “five Friends continue at the settlement at Tunesassah, endeavouring to instruct the natives in the arts of civilized life; for which purpose, two schools, one for boys and the other for girls, have been continued there…” Instruction in agriculture was undermined by “the circumstances attending these people at this time not being calculated to encourage them to exertions of this kind, as, since last year, the Seneca nation have been induced to part with very large bodies of their lands in different places…and it is feared this may be a prelude to their parting with the remainder at no very distant period. Notwithstanding these discouraging circumstances, it is believed, that by continuing to aid and assist these poor injured people, as long as there is any prospect of benefit, the objects contemplated by Society will be best promoted.”

The first religious group to oppose slavery, the subject was a constant theme. The 1767 Philadelphia Meeting notes “the Subject of some Friends neglecting the Christian Education of Negroes, & other Slaves in their possession, & detaining them in Bondage, hath been weightily under our consideration at this Time: It is again Recommended, that the care of Friends relating to those oppressed People in these particulars, may not be omitted; but that we proceed in true Love, to labour to excite to an upright Discharge of our Christian Duty towards them.” A much later 1827 Epistle reports an appeal by Carolina Quakers for funds for relocation, “there are 44 persons of colour who have intermarried with slaves and have 79 children. There are 20 married to those legally free, and have 50 children. That there are 316 disposed to remove to Liberia; 101 to Ohio and Indiana; 99 desire to remain where they now are; 15 choose to go to Philadelphia, and 86 are entangled in lawsuits… The total expense which will attend their transportation, it is believed, will not be less than from eight to ten thousand dollars…”

In a 1794 yearly Quaker meeting Extract, there is much attention devoted to spirits: both the purification of spirit brought about by baptism, and the perennial problem of distilled spirits, a subject “long painfully exercising to the Body.” Quakers were prohibited from “importing, or vending, distilled spirituous liquors, either on their own account or as agents for others, or distill or retail such liquors, or sell or grind grain for the use of Distillation.” The “Monthly Meetings should deal with them as other offenders, and… be at liberty to declare their Disunity with them.” Of course, this was a losing battle. By the 1797 Extract, the committee tasked with spirituous liquors “report we… are of the mind that not much, if any, advancement has been made in our Testimony against the use of those Liquors…”

A 1753 Epistle contains a wonderful reminder for Quakers to avoid other hazards “… many men amongst us putting on Extravagant Wiggs and wearing their Hats and Cloaths after the vain Fashions, unbecoming the Gravity of Religious People: and too many Women decking themselves with costly and Gaudy Apparel Gold Chains, Lockets, Necklaces, and Gold Watches exposed to open view; which shew more of Pride and Ostentation than for use and Service, besides their vain imitation of that immodest Fashion of going with naked Necks and Breasts and wearing hooped Petticoats; inconsistent with that modesty which should adorn their Sex, and did adorn the holy Women of Old… And in like Vanity of Mind divers amongst us run into great Extravagancies in the Furniture of their Houses… it does not become the Gravity of our Profesion, or any under it, to run into every new, vain, Fantastick mode or Fashion but to keep to that which is modest, decent, plain and useful… And that Parents in the Tender Years of their Children would not adorn them with Gaudy Apparel…”

The life of Thomas “Squire” Cheyney illustrates the difficulty of being a Quaker, who cannot take oaths, during those tumultuous times. A 1767 Epistle from London is written by Cheyney almost a decade before he was dismissed from the Quakers for enlisting. Cheyney became a sublieutenant for Chester County during the Revolutionary War. Serving from 1777-1783, his participation was significant, passing vital information to General George Washington of British troop movements. True to his Quaker heritage, Cheyney later founded the first African-American institution of higher learning in the United States.

Please join us to preview the February 19th and 20th sale, or visit us online at www.pookandpook.com to view these items and many other exciting finds. Whether it is an Epistle exhorting forbearance, or a diamond wristwatch, it is guaranteed that that you will be tempted by something.

by Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Part II of The Pewter Collection of Dr. Melvyn & Bette Wolf

In the Beginning

Pook & Pook presents at auction the renowned collection of John A. and Judith C. Herdeg of Mendenhall, Pennsylvania. The Herdegs were dedicated collectors with a lifelong passion for 18th century history and decorative art. Over their lives, they built one of the finest collections of Colonial American portraits in private hands. The Herdeg Collection is an important record of early Americans and artists.

Early portraits were available to the few who could afford it. During the latter half of the eighteenth century, burgeoning trade expanded the merchant and middle classes, expanding the number of Americans desiring to mark their achievements by recording their likenesses. Personal aspects such as social position, occupation, accomplishments, and character, were factored in to the composition of their portraits. Early American portrait painters collected by John and Judy Herdeg range from the very earliest to the brilliance of John Singleton Copley and Gilbert Stuart.

The artist known as The Pollard Limner (Boston, fl. 1690-1730) is identified on the basis of his 1721 portrait of Anne Pollard. He probably had no formal training as a painter, but painted in the Baroque Stuart tradition of the period. In the 1720’s, he was Boston’s leading portrait artist. The Herdeg portrait is of an ancestor of Judy’s, Elizabeth Bill Henshaw. Elizabeth was from a wealthy Boston merchant family and is portrayed before an Arcadian landscape.

Gerardus Duyckinck (New York, 1695-1746) is another early painter from New Amsterdam, from a family of glazier-limners that became America’s first dynasty of painters. He painted the prominent Dutch settlers of New York. Like much else in New Netherlands, his style was drawn from current Dutch culture, and employed a greater use of light and shadow to model the figure. In this portrait, in the words of John Herdeg, a young lady “is presented as a princess of the New World, with the untamed wilderness over the garden wall behind her.”

Works of both early artists are exceedingly rare.

John Smibert (American/British, 1688-1751) was America’s first professional painter. Trained in late Baroque portraiture in London and Italy, he was an established London artist. Invited to travel to Bermuda to teach painting at a new college for colonists, he sailed in 1728. Funding for the school never came through, and after a year of waiting, the project failed. Smibert then travelled to Boston. His 1729 arrival is regarded as a pivotal moment in American art. His superior skill made him one of the foremost portrait artists in colonial America. Boston’s wealthy merchant families flocked to him for their portraits. His studio displayed both his own works and old master copies, and extended his influence, remaining open over fifty years after his death. A talented architect, it was Smibert who drew the plans for Faneuil Hall, Boston’s first public market.

The portraits collected by John and Judy Herdeg trace the beginning and development of painting in America, and preserve for posterity the faces and ideals of early Americans.

Join us on January 16th and 17th, 2025, for our Americana & International sale to view the Herdeg Collection, as well as other important collections and estates.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence