NEWS

Love is in the Hair

Some of the most intriguing lots of jewelry in Pook & Pook’s upcoming Coins & Jewelry auction include examples of Victorian hair jewelry (Lots 1959, 2525, and 2584). The practice of incorporating human hair to create intricately designed bracelets, brooches, lockets, and braided watch chains has its roots in the 17th and 18th centuries, when infant mortality rates were high. Alfred, the fourteenth child, and youngest son, of King George III and Queen Consort Charlotte succumbed to complications following a smallpox inoculation. After Alfred’s passing in 1782, Queen Charlotte sent the child’s governess a lock of his hair enclosed in a locket of pearls and amethyst expressing in a letter “Receive This … as an Acknowledgement for Your very affectionate attendance upon my dear little Angel Alfred, and wear the inclosed Hair, not only in remembrance of that dear Object, but also as a mark of esteem from Your Affectionate Queen.” This piece is now housed at The Royal Collection Trust.

Alongside elaborate mourning attire and post-mortem photography, these distinctive hair jewelry pieces peaked in popularity during the 1860s following Queen Victoria’s loss of her husband. After Prince Albert’s death in 1861, Victoria entered a period of mourning that lasted up until her passing in 1901. Along with wearing black while mourning, she also wore a locket containing Albert’s hair. This encouraged the act of mourning loved ones to become fashionable, not only in England but America as well.

The Civil War also played a significant role in driving this trend in the United States. Civil War soldiers would often leave a lock of their hair before going to war; women would hold on to their sweetheart’s hair as a way of keeping their loved one close while they were away. Sadly, this keepsake also served as a tangible memory of those soldiers who never made it home.

Hair keepsakes did not always corelate to death. Women would send their sweetheart a lock of hair and a photograph in valentines and postcards. Couples who got married would have braids created from strands of their hair, which would then be incorporated into a wedding band. Hair served not just as a medium for jewelry, but also for creating art and family trees. Hair serves as a lasting memento because it can endure for decades, or even centuries, thanks to its protein structure.

Eventually, the trend of making jewelry from hair declined in popularity for several reasons, including the onset of World War I, the advent of funeral homes, and the rise of the Women’s Rights movement that introduced the “bob” hairstyle. There are still echoes of this long-lost art in our modern world; you might take your child for their first haircut and ask the stylist to save a lock of hair as a token of the occasion. One-of-a-kind hair jewelry pieces such as those in our upcoming sale are an ode to a person’s essence. Each piece declares: “I Loved…”. How special it is to be able to own such a rich piece of someone’s personal history.

By Erika Lombardo

Bibliography:

- com: The Ugly History of Beautiful things: Lockets.

- Wikipedia

- Kentucky Historical Society – Artworks with Human Hair: Victorian Pastimes and Mourning Customs.

- com: The Curious Victorian Tradition of Making Art from Human Hair

- Rosenberg Library Museum : Victorian Hair Jewelry

- The Order of the Good Death: They’re Not Morbid, They’re About Love: The Hair Relics of the Midwest

- com: Hair Jewelry

Off the Grid

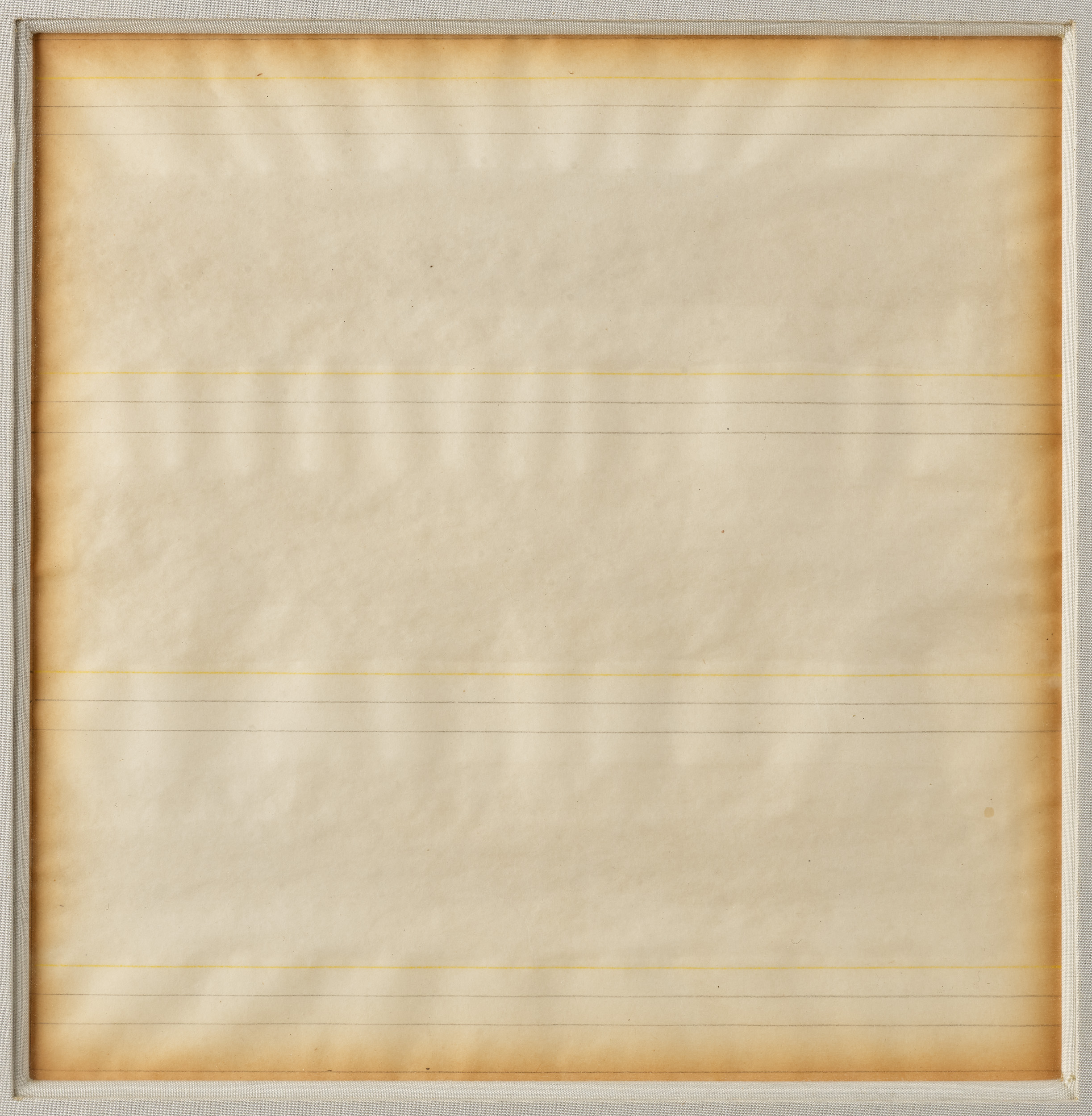

What does the sensation of beauty look like in a painting? The challenge for Agnes Martin was not to paint a beautiful object, but the sensation of perceiving it; that, when looked at, would be felt by others. “My paintings are not about what is seen. They are about what is known forever in the mind.”

Born in 1912 on the plains of Saskatchewan, Martin moved to Washington state at the age of 19 to live with her sister. She stayed in the US for higher education, first training as a teacher at Western Washington University and Columbia, and then the University of New Mexico for fine art and Columbia for modern art.

Emerging from two decades of education at the age of forty, she moved from New Mexico to New York City and lived amongst avant-garde artists in Coenties Slip, lower Manhattan. Other artists in her circle of friends included Ellsworth Kelly, Lenore Tawney, Ann Wilson, and Robert Indiana. Martin’s New York heyday was the decade from 1957 to 1967. Drawing inspiration from transcendentalism, Taoism, and Zen Buddhism, she became a minimalist pioneer. Her art took the form of 7 ft square grid-lined canvases. She was photographed on ladders plotting gridlines onto the canvas with rulers, tape, and string. Why gridlines? “I was thinking about innocence, and then I saw it in my mind-that grid,” she told critic Joan Simon. She sought perfection and to see transcendental reality, without letting technique or subject matter stand in the way. She believed spiritual inspiration, not intellect, created great work. Her goal was to not have ideas, to have a vacant mind, and wait for inspiration to guide her. Her paintings were of happiness, innocence, and beauty. She sought to portray the intangible experiences in life, unconfined by form. Her works are free of subjects. They are ethereal, summoning joy in the observer.

Martin was a groundbreaking artist and gained recognition for her uniqueness. Finding success in her career, privately she struggled to cope with debilitating paranoid schizophrenia. She was frequently hospitalized over her decade in New York with aural hallucinations and states of catatonia. She was treated more than once with electroshock therapy. Martin has been endlessly romanticized, withdrawing into herself, creating with her art the balanced, tranquil spaces in which she found happiness.

Agnes Martin’s decade in New York came to an end in a convergence of adverse events: her studio building slated for demolition, the death of a friend, and the end of a romance. She burned all her art and gave away her painting supplies. She packed an Airstream camper and hit the open road, traveling the western US and Canada. Eighteen months later she settled in New Mexico on a remote mesa. There she lived a monastic lifestyle, focusing on study and writing. She had no electricity, plumbing, or telephone. She wrote to Sam Wagstaff: “… but even more fantastic I do not think that there will be any more people in my life.”

In 1973, Martin found a new mode of expression that revived her interest in painting. “One time, I was coming out of the mountains, and having painted the mountains, I came out on this plain, and I thought, ‘Ah! What a relief!’ (This was just outside of Tulsa.) I thought, ‘this is for me!’ The expansiveness of it. I sort of surrendered. This plain… it was just like a straight line. It was a horizontal line. And I thought there wasn’t a line that affected me like a horizontal line. Then, I found that the more I drew that line, the happier I got. First I thought it was like the sea… then, I thought it was like singing! Well, I just went to town on this horizontal line.”

Represented by Arne Glimcher and Pace Gallery, she experienced financial success for the first time. Martin was able to purchase her own home, and was able to travel and exhibit at her own pace. Belying her reputation as a recluse, in her last decade Martin became involved in children’s and community projects, donating millions of dollars to bring joy and happiness to the residents of Taos. She died in Taos in 2004.

For your chance to own a work by Agnes Martin, please join us at Pook & Pook for our September 25-27th, 2024 Americana & International sale.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Bibliography:

Christopher Regimbal, Agnes Martin Life & Work

John Gruen, The Artist Observed

Henry Martin, Agnes Martin: Pioneer, Painter, Icon

A Stark View of the Civil War

Wm. B. Stark’s Campaign, in the war of 1862-63-64 and 65.

Written by himself from his diary kept during the war.

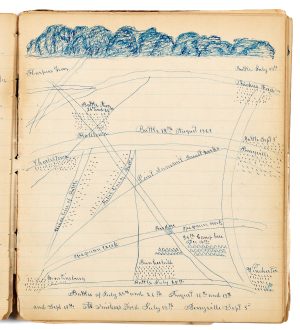

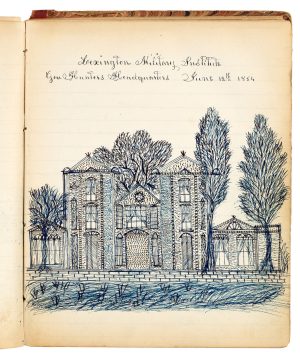

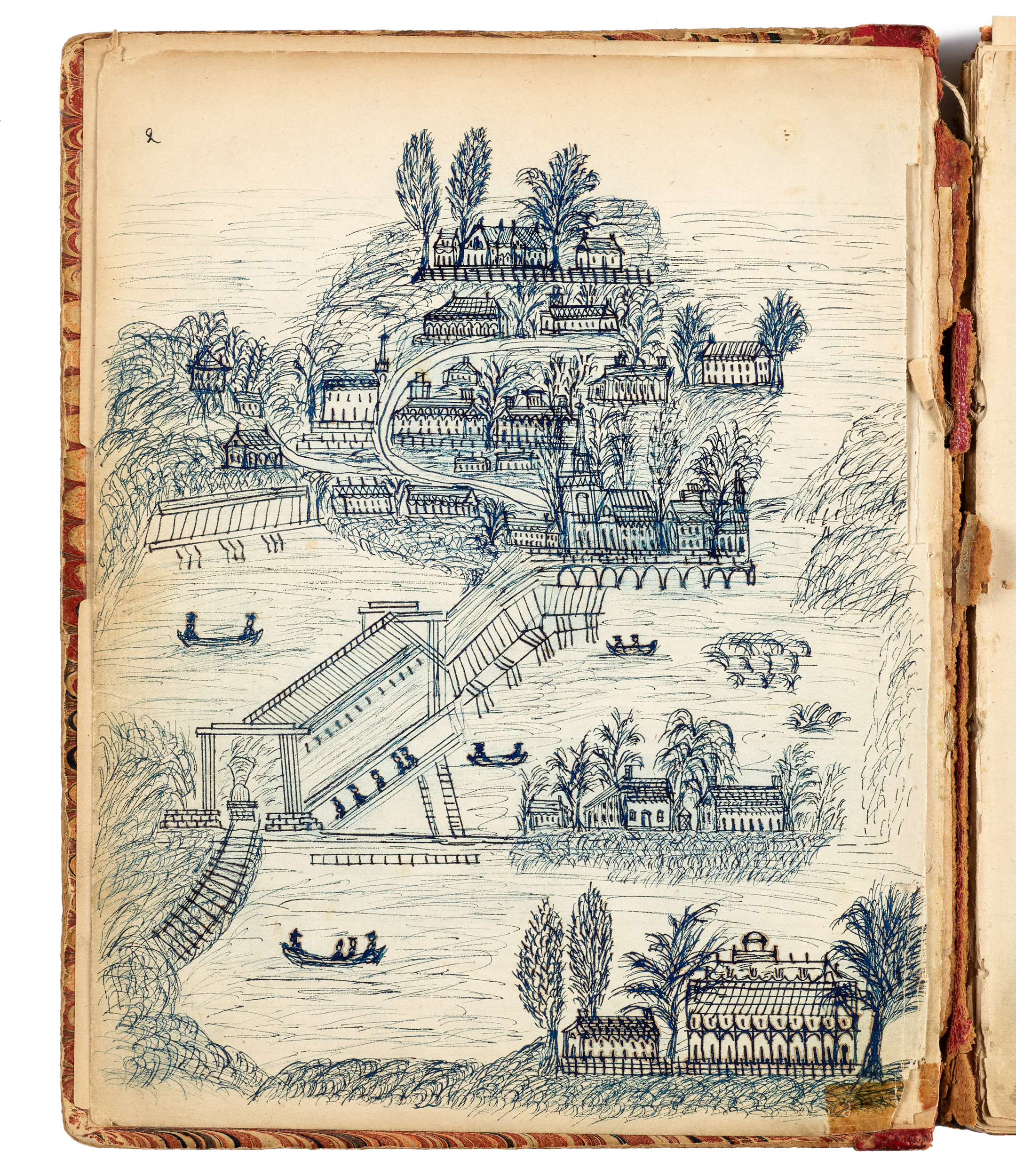

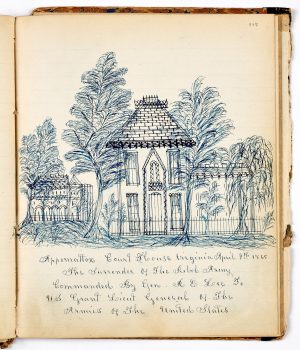

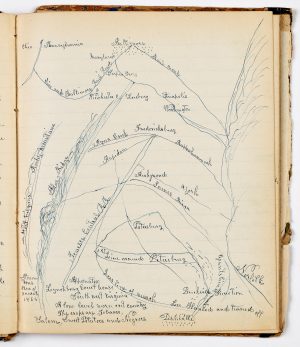

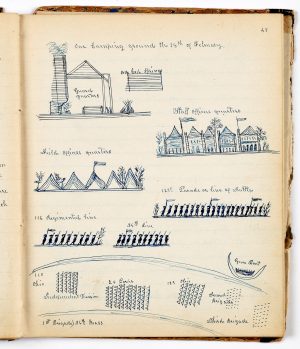

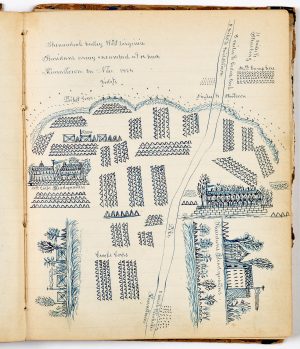

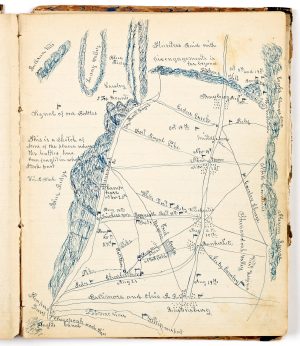

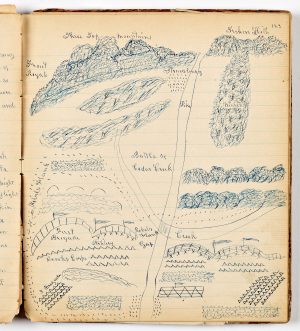

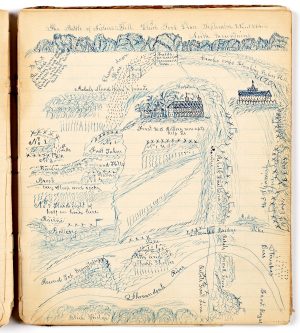

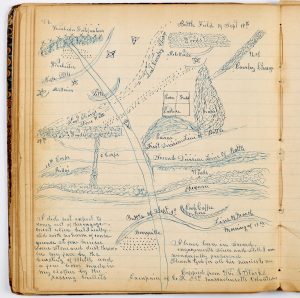

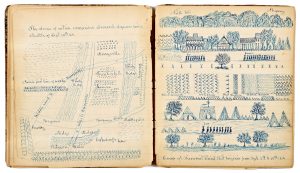

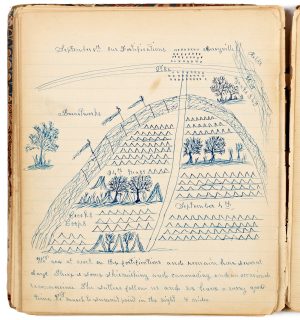

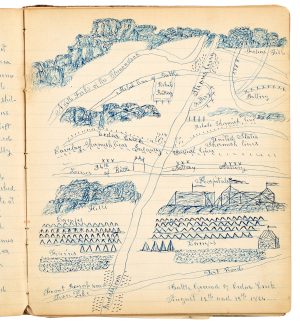

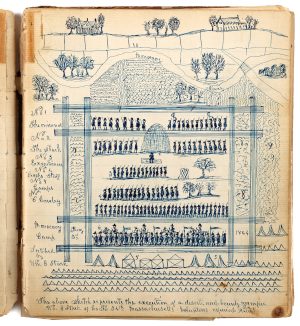

William B. Stark kept a diary of his days serving in the Civil War, a fascinating first-person historical account of the 34th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers. Stark tells tales of harrowing escapes, hard labor, endless marches, extreme temperatures, fearsome battles, and patriotism. Day after day he records his experiences, and the history of the Civil War.

Recruited in 1862, the 34th spent long months learning on the job, marching, drilling, and picket detail. Stark itemizes everything included in the soldier’s packs, and the weight: over 100 lbs. The troops also guarded everything from camps to railroads, Unionist houses, and prisons. In the prisons the inexperienced men were sometimes greatly outnumbered in open rooms, surrounded by enemy soldiers, but what they dreaded the most was guarding the female prisoners, because of the barrage of foul-mouthed abuse. (While Stark refers to these insults more than once, he unfortunately did not preserve any of them for posterity.) After crossing the Potomac at Harper’s Ferry with General Mead, the 34th saw its first action August 18th, 1863 in the Battle of Ripon. On the move over the next months, challenges became greater, “A cold day with rain and sleet. The rain freezes on our clothing and loads us down with ice. The bridges are burned and we for(d) the streams to the armpits, a tedious time. We camp at Woodstock in the woods at 3 P.M. 12 miles. We build fires after a long time everything being soaked with water and covered with ice. It was hard making a fire… We fall in line try to fire off our pieces but cannot…” Little did Stark and the 34th realize, what was to come would be infinitely worse.

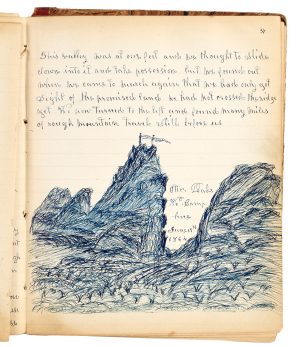

Volume II of the diary begins with news that the 34th is going to Lynchburg under General Hunter’s command, in what became known as the Lynchburg Campaign. They were to march through hostile territory, inadequately provisioned as they would be living off the land. Expected reinforcements from General Sheridan were held up and, reaching Lynchburg, Hunter found himself critically outgunned by the Confederates. The battle quickly turned into a retreat. Stark was shocked: “When any one would mention such a thing on our way down I would tell them that such a thing was out of the question. We must and would take Lynchburg at all hazards; rations we must have and we could get them only at Lynchburg. We could never retreat, that was impossible. If we were not all captured we should most certainly starve.” Stark recorded in detail the daily sufferings on retreat. Pursued through the mountain wilderness of West Virginia, the troops retreated for a month towards safety in Ohio. In the mountain passes they lost artillery and many horses, and were forced to burn wagons. Soldiers too poorly to cross the peaks were abandoned to die. Stark details his daily struggle to keep marching, leaving behind tents and even ammunition to lighten his burden. Drought and starvation claimed many. Meanwhile, the Confederates under General Early marched unimpeded through Maryland, a double humiliation.

Volume III opens with the exhausted troops marched back towards the action. Engaging with increasing frequency, the 34th still wore their uniforms from the Lynchburg Campaign debacle, and were nearly naked and shoeless. “July 25: We have a heavy cold rain. We are barefoot and many have no tents, blankets, rubbers, or anything to make them comfortable and we are obliged to lie out in the cold rain.” There is great relief when General Wells ordered the 34th to bathe in the creek and receive new uniforms and kit. Smartly dressed, the spent troops were then marched towards Pennsylvania to cut off the rebel army. In the intense July heat many were lost, falling out on the side of the road. Stark himself fell out, exhausted and delirious. In desperation, after an hour’s absence, he was able to pull himself together and continue. Daily diary entries detail the skirmishing, which at this point was intense, and nearly constant.

September 19th saw the 34th engaged in the bloody Third Battle of Winchester, in which thousands were lost on both sides, including about a third of the Rebel forces. Stark writes of the charge, “The shot, shell and grape was now poured in perfect showers for we were now in range of their heavy Artillery and several battalions were blazing away at short range carrying death at every discharge. Col. Harris rode in front of our lines like a mad man shouting ‘Come on boys’ and swinging his broadsword over his head.”

A few short weeks later, the battle-hardened 34th engaged again in the Battle of Cedar Creek, another bloody and desperate fight in which they lost half of their men and their beloved commanding officer Colonel Wells. They fought again in the Appomattox Campaign, including the Fall of Petersburg and the Pursuit of Lee. Stark describes every battle, every camp, and every day in precise detail. His account of the thick of the battle of Petersburg is harrowing: “The noise was terrific. The smoke of a thousand furnaces and the roar of many thunder storms could not have equaled the scene before us. We marched and drew up before that nothed spot. The air was full of bursting shell. The forts looked like volcanoes belching forth their liquid fire.”

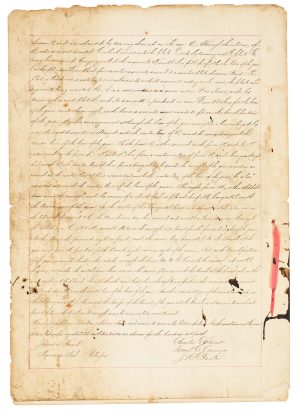

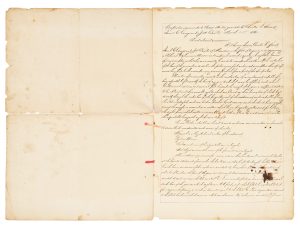

Stark’s journal is full of elaborate drawings of the many camps, marches and battles of his campaign. This first-person, detailed record of the daily life of a soldier is of great historical value. Stark was both a participant in and a witness to pivotal moments in the history of the nation. Please join us on September 25, 26, and 27th for a chance to bid on this important piece of American history.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Lot 1340

Press Release – September 2024 Americana & International Auction

Downingtown, Pennsylvania – Pook & Pook will hold our largest Americana & International sale ever, spread over three days, September 25, 26, and 27th. The sale features important single owner collections, as well as many items from private collectors and institutions.

Day One encompasses two important private collections. The first is the folk art collection of Albion P. Fenderson of Modesto, California. Al and Florence Fenderson were avid collectors in Southeastern Pennsylvania before moving to California in the 1960’s. The quality of the Fenderson Collection folk art is exceptional. Paintings include a pair of William Matthew Prior husband and wife portraits, a colorful Samuel Miller portrait of a boy in a red dress with a hobby horse, and a rare Isaac W. Nuttman still life with a bird and an abundance of fruit. A rare Samuel Folwell Philadelphia watercolor silhouette of the Reverend Absolom Jones is of historical importance. The first of several in the sale, a Wilhelm Schimmel spread winged eagle is outstanding for its vibrant original painted surface and imposing size. The highlight of the collection is a highly important ink and watercolor fraktur Taufwunsch by the Sussel-Washington Artist. This vibrantly colored fraktur is the finest example in private hands, rivalling any institutional holding.

Pook & Pook is honored to present the finest and most comprehensive collection of American pewter in history, unequaled by any other institutional or private collection at any time. The Collection of Dr. Melvyn and Bette Wolf of Flint, Michigan, is a once in a lifetime assemblage of American pewter of superb quality and significance. The foremost of many highlights is a highly important Philadelphia William Will coffee pot, which is considered to be one of the finest pieces of American pewter in existence. Other rare pieces include the only Robert Bonnynge church cup in private hands, a Semper Eadem quart tankard, a Frederick Bassett egg-shaped teapot, and a Johann Heyne ciborium. The Wolfs’ love of Americana went well beyond pewter and included New England furniture, decorative arts, and folk art paintings. A few to mention are an exceptional set of ten Pennsylvania painted treenware lidded cannisters, a collection of New England burl bowls, and fine folk art paintings, including two Hudson River landscapes attributed to Thomas Chambers, and two Jonas Welch Holman portraits, of Mary Ann Bassett and of the Bassett children.

A Maryland theme is found in a Historic Blue collection featuring a Baltimore tea service and pieces in the rare Arms of Maryland pattern. A rare pair of Thurmont, Maryland redware vases is attributed to James Mackley, and a Thurmont planter is inscribed Jacob Lynn Pottery and dated May 18, 1845.

Additional Day One Americana highlights are a provenanced swell-bodied copper lamb weathervane, fraktur, a pair of Pennsylvania flame grain painted doors, and Pennsylvania Chippendale cherry tall chest, and a large Pennsylvania folk art carved kangaroo from the Ralph Esmerian collection.

Day Two opens with the Collection of Rebecca Roberts of York, Pennsylvania. Ms. Roberts was passionate collector of local antiques. Furniture includes a blanket chest with vibrant paint decoration by William Heindel, and tall case clocks signed Jacob Spangler, and Peter Schutz Urmacher. Textiles include samplers, needlework, and quilts. Featured coin silver is by Godfrey Lenhart. There are many fraktur, including York County examples by Francis Portzline, Daniel Peterman, and Adam Wertz. Among the Jacob Maentel watercolor portraits are York County residents. Other Pennsylvania furniture includes a Lancaster corner cupboard, and a Northampton County painted pine dower chest. Ms. Roberts’ keen interest in Bellarmine and Westerwald stoneware is evident in her large collection spanning the 17th and 18th centuries.

Next up are thirty-eight lots of American glass, including a Stiegel type deep amethyst flask, and many with provenance from illustrious collectors such as Walter Douglas, Lowell Innes, and John Tiffany Gotjen, the latter including a New York blown aquamarine lily pad compote.

The first group of great weathervanes from a prominent Washington D.C. collection includes a swell-bodied copper bull, a cast iron horse, probably Rochester Iron Works, a sheet copper hound dog attributed to Howard & Co., West Bridgewater, Massachusetts, and a full-bodied copper stork, ca. 1900, attributed to J.W. Fiske & Co., and many more.

Noteworthy iron items include a wrought iron Conestoga wagon fish-form axe holder, ca. 1800, a painted cast iron Chinaman hitching post, late 19th c., and a cast iron kicking donkey carnival target by Wurfflein, Philadelphia.

A New Jersey collection features four colorful barber poles.

An Ohio collection reveals a lovely Philadelphia broderie perse chintz applique friendship quilt.

Furniture highlights of the day include a Chester County Pennsylvania tall case clock with works signed Ellis Chandlee Nottingham, and a graceful Bermuda Queen Anne cedar blanket chest. Great painted furniture includes a Pennsylvania blue painted hard pine schrank, ca. 1770, a diminutive Mahantongo Valley school masters hanging desk, a Virginia dower chest, and a Berks County blanket chest attributed to Jacob Blatt, with original salmon fan and circle paint decoration.

Fraktur include works by David Cordier, Reverend Henry Young, and an outstanding Daniel Otto.

Important stoneware includes a rare water cooler impressed Wells & Richards Reading Berks Co. PA, a three-gallon jug impressed Cowden & Wilcox Harrisburg PA, and a Reading mug impressed John G. Slocker 1895, with underside inscribed Harry Zerby.

Day Three begins with the Collection of Walter Pyle Smith and Jeannette Chaffee Smith of Gettysburg. The Smith’s life-long love of antiques resulted in an exceptional collection of Pennsylvania German decorative arts. One of many highlights is a Compass Artist paint-decorated dome lid box retaining its original rare salmon surface. Not to be missed are two Jonas Weber painted pine dresser boxes and two Wilhelm Schimmel spread winged eagles. Other carvings include an important Aaron Mountz large bird. The Smiths also collected fine redware, including a Southeastern Pennsylvania sgraffito charger dated 1811 with eagle decoration, a Snow Hill Nunnery bowl, a Solomon Bell, Strasburg, Virginia mixing bowl, and two large Hagerstown, Maryland bowls, one possibly from the Bell family. A menagerie of redware spaniels, poodles, lions, and birds includes a dog holding a fruit basket attributed to Jesiah Shorb. A Bristol County, Massachusetts bean pot is one of several items with a Dr. and Mrs. Donald A. Shelley provenance. A pair of North Carolina Moravian redware squirrel bottles is attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem. The Smith’s Pyle and Wyeth heritage is evident in artworks by Howard Pyle in watercolor, oil, and ink, and an Ann Wyeth McCoy watercolor. Rounding out the collection are works by Edward Moran and Frank Earle Schoonover.

The fine art category opens with Taos Art Colony co-founder Ernest Blumenschein and his landscape Autumn with Storm. A panorama of landscapes includes several by Maryland/Washington D.C. painter John Ross Key, a Max Weyl Washington D.C. landscape The Little River, Georgetown, a Jack Wilkinson Smith California coastal scene, a Peter Sculthorpe watercolor on paper of a moonlit winter homestead, a Gladys Young street scene, and other landscapes by John Prentiss Benson, Thomas Curtin, Hugh Bolton Jones, Richard Norris Brooke, and John Henry Witt. Of two landscapes by Samuel Lancaster Gerry, there is a fine view of the White Mountains. Rounding out the paintings are three works by Ben Austrian.

Modern art highlights include a Carl Milles bronze Bird of Prey, a Louise Nevelson plaque City Sunscape, a Jasper Johns screenprint in colors The Dutch Wives, a Wolf Kahn pastel Spring Barn, and an Agnes Martin watercolor, graphite, and colored pencil work from a York County, Pennsylvania estate.

Three more weathervanes from the Washington, D.C. collection are a large swell-bodied copper cow, a painted copper trolley, a swell-bodied copper prancing horse attributed to A.J. Jewell & Co., Waltham, Massachusetts, and a New England painted sheet iron clam digger.

From a Washington, D.C. collection comes an item of historical importance: a series of Civil War ledgers by William B. Stark of Egremont, Massachusetts, with detailed entries and elaborate drawings of battles and camps.

A graceful New York Chippendale carved serpentine front card table is not to be missed in furniture.

A rarefied collection of twenty-six lots of 15th through 18th century European copper alloy candlesticks includes North West Gothic and rare Three Kings examples, and English candlesticks including rare bell base and very rare Gothic examples.

Please join us to preview, online or in person, for this important sale.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Where there’s a Will

The history of pewter in America is representative of the wider colonial experience. In the late 17th century, Britain passed a series of laws called the Navigation Acts governing colonial trade. The Acts limited the colonies to trading with Britain, and increased Britain’s advantage by imposing further restrictions and duties on colonial trade. In this system of political economy, later labeled Mercantilism by Adam Smith, government regulation of the economy was for the purpose of building state power and wealth. Colonies existed for the economic benefit of the imperial power.

Pewter is an alloy of mostly tin, which Britain mined in Cornwall. The colonies lacked a source of tin, but could not purchase tin from Britain. They could only purchase finished pewter merchandise and pewter ingots, which because of tariffs cost as much as the finished products. Britain had a thriving pewter industry to protect, governed by a London guild set up in 1473, and selling to the colonies while impeding the development of local manufacturing ensured a favorable balance of trade.

Pewter was in great demand in America. Annual pewter imports from Britain had grown to more than 300 tons by 1760. Connecticut pewterer Thomas Danforth Boardman wrote “From the Landing of the Pilgrims to the Peace of the revolution Most all, if not all, used pewter plaits and platters, cups, and porringers imported from London & made up of the old worn out,” (Montgomery). Pewterers in the colonies resourcefully purchased worn out pewter from households, which they melted down and reworked. Pewter is a soft metal and most pieces had a useful life of about ten years before becoming misshapen. American pewterers exchanged of reworked merchandise for customers’ old worn pewter. Because of the necessity of melting and reworking, American pewter today is more valuable than British pewter. There is simply less of it.

A colonial pewterer would assay old pewterware into different grades to be melted down and then poured into his assortment of molds. The molded pieces were fitted and soldered together to create coffeepots, sugar bowls, creamers, etc. Since a pewterer only had so many molds, the shapes were used interchangeably for different pieces. The same mold could be used for the lid for a teapot or the base of a chalice. A flagon could be assembled from as many as fourteen parts, all of which had to be useful in creating other wares.

William Will brings us to the conclusion of our study of American pewter and mercantilism. His story has been told often, but is a good one, and neatly illuminates the result of England’s trade policies. William Will (Philadelphia 1742-1798) is regarded as the finest American pewterer of the 18th c. “His ability to make new designs by using interchangeable parts cast from existing molds was unequaled by any other American pewterer,” (Herr). A German immigrant from a family of pewterers, William practiced in Philadelphia, and was so successful that he achieved status as a leading citizen. “No other has left a more impressive evidence of ability, and few approached the craftsmanship which his pewter displays. Gifted beyond most of his fellows, he unselfishly subordinated his business to a life of service to his community and demonstrated that he was not only a superior craftsman, but also a splendid soldier, a capable statesman, and an executive of unusual ability,” (Laughlin). William Will contributed to ridding the American colonies of the effects of British mercantilism. Forming an infantry company in 1776, he served as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Philadelphia Militia’s 3rd Battalion in 1777 and 1780. Much was asked of him, as in 1777 he was also appointed one of six Commissioners for the seizure of traitor’s property, in 1779 named storekeeper in Lancaster for the Continental Army, in 1781 was elected sheriff of Philadelphia, and in 1785 was elected, along with Robert Morris, to the General Assembly in the newly independent United States of America.

Pook & Pook invites you to join us for our September 25-27th Americana & International sale, which will feature important American pewter, and many pieces marked by William Will himself.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Bibliography

Charles Montgomery, A History of American Pewter, Winterthur, 1973.

Donald Herr, Pewter in Pennsylvania German Churches, Pennsylvania German Society, 1995.

Ledlie Laughlin, Pewter in America, Houghton Mifflin, 1940.

Don’t Take Candy from Strangers

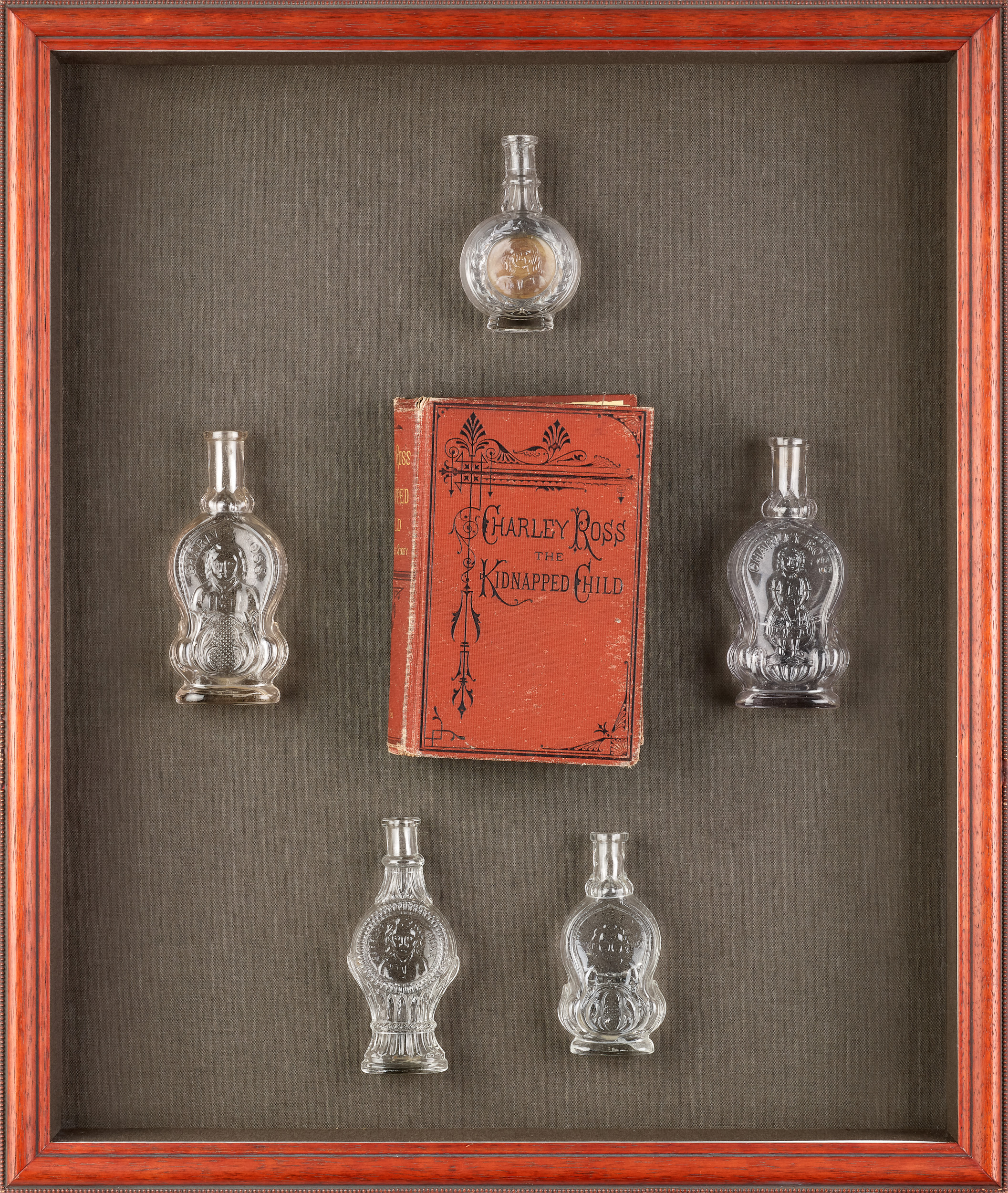

Two lots not to be missed are #248 and #317. They are a glass perfume bottle and a shadow box frame containing five bottles and a book, items easy enough to walk past without a second glance—but once their context is understood, they are impossible to forget.

In July 1st, 1874, in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia two brothers, ages four and five, were playing in their front yard when they were lured into a wagon by two men who had been seen giving them candy on several occasions. The older boy, Walter Ross, was found miles away outside a store. The younger boy, Charley Ross, was never seen again. Soon afterwards, their father Christian Ross received the first of many shocking ransom demands, $20,000 for the return of his son. Ross had lost a great deal of money in the stock market collapse of 1873 and did not have $20,000. He turned to the Philadelphia police department for help.

The organized police force had only been around for two decades before Charley was kidnapped. The police and the city had no idea what to do. The kidnapping of Charley Ross was the first recorded kidnapping for ransom in the United States. There were no procedures to follow. Kidnapping wasn’t even recognized as a crime, and many crimes were ignored, either because they were not yet recognized as crimes, or because the fledgling institution was still short of attaining the professionalism needed. Because of low pay, policemen were allowed to claim monetary rewards for solving old cases, and many police worked second jobs as thief catchers, compromising their integrity.

People had little faith in the ability of the police to catch the kidnappers. The New York newspapers were instantly critical of Philadelphia’s force. Once the Philadelphia newspapers expressed frustration over the lack of success, a city-wide effort began- which quickly became nationwide. Once the City posted a $20,000 reward for information leading to the capture of the kidnappers, everyone became a detective. People reported sightings of strangers with children, and searched gypsy camps and the countryside. Reports flooded in from all over the nation. Civilian search parties scoured the city. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote “Almost every man has been a detective in the case.” Charley’s disappearance became a cultural phenomenon. Sentimental songs were written imploring for his return. Leaflets and posters were put up everywhere, many paid for by the Ross family. Christian Ross also wrote a book, a personal narrative of the tragedy. Glass bottles were impressed with Charley’s image, like an earlier version of today’s milk carton children. The general population’s obsession lasted for decades, the nation riveted by a tale of true crime.

The City of Philadelphia, led by Mayor Stokely, who was himself directed by an unofficial committee of party advisors, advised Mr Ross not to pay the ransom, fearing it would lead to a kidnapping epidemic if the criminals could snatch a child and get paid $20,000. Their motives will never be fully known, but one major concern was the upcoming Centennial Exhibition of 1876, the first World’s Fair to be held in the United States, and the centennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia was spending hundreds of thousands of dollars preparing the city for a huge influx of visitors. If the kidnappers were successful, how would any family feel safe bringing children into the city? The Mayor and the committee advised Christian Ross not to give into the kidnapper’s demands. They helped the Ross family by responding to the ransom notes, always putting off the payment. More helpfully, the City ordered a search of every house, and changed the law to make kidnapping a crime and established sentencing for it. The City’s grandest gesture, the $20,000 reward, had unforeseen consequences.

While the New York papers were highly critical of the Philadelphia police force’s competence in the case, it was one of their own police who impeded its resolution. NYC Superintendent George Walling received a report from an officer who had immediately recognized the description of the kidnappers: William Mosher, a middle-aged river pirate and known criminal whose nose cartilage had been destroyed by syphilis, leaving him with a shortened, highly distinctive snout, and Joseph Douglas, a young career criminal with bright orange hair. They lived in Philadelphia but were frequently found in the Five Points neighborhood of New York City, organizing and committing crimes. Mosher’s wife was the sister of a former NYC police officer, William Westervelt. Once this connection was made by Superintendent Walling, he hired Westervelt to spy on his sister’s husband. Months passed with no new developments, other than a series of malign ransom letters and news speculation. Walling could at any time have arrested Mosher and Douglas, but he waited until he could get irrefutable evidence, and perhaps Charley himself, because then he could legally claim the $20,000 reward.

But Westervelt was a double agent, informing the kidnappers of the police department’s every more. The sinister ransom letters continued. Mosher and Douglas returned to river pirating, and were shot one night while robbing a home on Long Island. As he died, Douglas confessed to the kidnapping, and said that Mosher knew where Charley was, not knowing that Mosher was already dead.

Even though Westervelt was later imprisoned as an accomplice in the cover-up, Superintendent Walling escaped any blame. In her 2011 book on the subject “we is got him”, Carrie Hagen reasons that Charley had remained, except during the city-wide search, in Philadelphia the entire time, mingled in amongst the four or five children of the Mosher household. During this time, one of the Mosher children died of an illness. The dead child was likely Charley. Martha Mosher never confessed any involvement in the crime, but in interviews muddled her children’s ages and names, especially that of the deceased child.

The Ross family never stopped searching for Charley, and spent some $60,000 on the effort to recover him. Meaghan Good, founder of the largest online database of missing persons, named her creation The Charley Project in honor of him. Today, the database counts nearly 16,000 missing persons, and of Charley, Ms Good notes “He was basically the Lindbergh baby of the 1800s.” A cultural icon, the law was changed because of his abduction, the nation’s thoughts were focused on his return, helping to pull the populace together after the divisions of the Civil War, and we have the universal childhood admonition “Don’t take candy from strangers.”

by Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Barry Hogan’s Cherished Collection

An Introduction to Barry Hogan’s Cherished Collection

Welcome to a remarkable journey through Barry’s legacy. His name is revered across Lancaster County not only for his impactful contributions to real estate development but also for his profound passion for the world of antiques. At the heart of Lancaster, Barry’s endeavors redefined skylines and neighborhoods, showcasing his deep-rooted love for the community he helped shape.

Barry’s journey into the realm of antiques began in the early 1970s. Over five decades, he meticulously curated one of the nation’s most esteemed collections of early American historical flasks. However, Barry’s affinity extended far beyond the shimmer of glass. He was a connoisseur of Pennsylvania folk art and early Americana. His approach to collecting was far from the leisurely pastime of a hobbyist. For Barry, it was an avocation—a calling that he pursued with the fervor and dedication of a true devotee.

Each piece in Barry’s collection tells a story of his unbridled enthusiasm and discerning eye. He sought not just the rare or the exquisite, but also examples that spoke to him personally, which he considered the ‘best’ by his own unique standards. This selection process was not simply about prestige or value alone but about a deep, intrinsic connection to the heritage and beauty each piece represented.

Barry’s expertise wasn’t confined to collecting; it extended to understanding and appreciating the nuanced histories of each item. His journey from a young enthusiast to a revered figure in the collecting world is a testament to his knowledge, boldness, and exceptional eye for detail.

As we embark on this auction journey, we extend a warm invitation to explore examples of Barry’s magnificent collection. While we deeply feel his absence, his legacy lives on through these artifacts. They weren’t just part of a collection but a pivotal part of his life. Here, we share his lifelong avocation, not just with collectors but with anyone who appreciates the timeless beauty and historical significance of Americana and Pennsylvania German antiques.

Barry’s collection will be sold at auction on Friday, May 17th, 2024 at Pook & Pook’s gallery in Downingtown, Pennsylvania. For more information, please visit www.pookandpook.com.

Americana & International Sale

The April 18th & 19th Americana & International Sale at Pook & Pook will offer one of our broadest assortments of antiques and art to date, everything from antiquities to Amish quilts, English delft chargers to Chinese Export platters, stoneware to redware, Gothic brass candlesticks to American silver, pewter, and iron, fraktur to modern art, early American glass to Native American objects. The second day of the sale is devoted almost entirely to several international collections, including that of Robert S. Miller.

The sale will have all that one expects from Pook & Pook. Always strong in folk art, the auction features a Schimmel eagle, a Mountz poodle, a fine cigar store Indian, and a massive Noah’s Ark on a custom shelf with eighteen feet of switchback ramp on which 194 animals can be lined up to board. Elaborately carved Northern European mangle boards, tramp art frames, an excellent miniature painted stool and miniature blanket chest, Bucher boxes, a Compass Artist dome lid box, and saffron cups by Joseph Lehn compete for attention. Fraktur features rare works from Mahantango Township, Schuylkill County, and the Springing Deer Artist, with Mrs. and Dr. Donald Shelley provenance.

Pook & Pook sales are also always strong in furniture, from Philadelphia Chippendale tables to Pennsylvania William and Mary high chests, to New England Queen Anne tiger maple high chest, a large New Jersey or Pennsylvania William & Mary walnut gateleg dining table, and a pair of Boston Queen Anne dining chairs. The Jonathan Paschall Pennsylvania Queen Anne dining chair is in a wonderful state of preservation and has descended in the family. One standout is a Pennsylvania walnut chest on frame, with allover line and fan inlays, dated 1791 and signed. The headline furniture item is the William Barch, Lancaster, Pennsylvania Chippendale carved walnut desk and bookcase, signed by cabinetmaker William Dennis and dated 1789. Colorful painted furniture is also always present, with Pennsylvania German dower chest from Center and Lancaster counties and a painted chest of drawers providing highlights. There are always fine tall case clocks at Pook & Pook, exemplified in this sale by an important Philadelphia Chippendale walnut clock with eight-day works signed Jacob Godshalk Philadelphia.

A large swell-bodied copper rooster, a full-bodied Cushing & White running horse, and a swell-bodied gilt copper bull are a few of the wonderful weathervanes offered. From an Aspen, Colorado collection comes an assortment of wrought iron.

Baseball memorabilia always hits a home run at Pook & Pook. This sale presents a scarce McLoughlin Bros The World’s Game of Base Ball, copyright 1889.

Redware and stoneware categories include a rare Pennsylvania redware lidded crock signed John Boll 1832, a rare Pennsylvania sgraffito mug dated 1797, a North Carolina painted redware face jug, a Lanier Meaders stoneware face jug, Remmey type and Cowden & Wilcox stoneware, just to name a few.

The influence of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts is seen in works by artists such as John McCoy II, Philip Jamison, Jr., Antonio Martino, Seymour Remenick, Ezio Martinelli, and Walter Baum. Other featured lots include Philadelphia artists Robert Conover and Earl Horter, Jacob Maentel, and works by J. Alden Weir and Beatrice How. Two 1930’s oil on canvas paintings for the covers of American Legion Magazine depict wintry scenes by Lester Stevens and Magnus Colcord Hendon. The highlight is a massive mixed media work by Lawrence Carroll titled “No Patience for the Past”.

Another strong specialty for Pook & Pook is Native American Indian art and antiques. Historical items descended in the family of the Hon. Lewis V. Bogy, Commissioner of Indian Affairs under President Andrew Johnson, 1866-67, lead the category with moccasins and beadwork, kachina dolls, photographs, and two portraits in oils of Native American dignitaries. Items from the collection of Douglas and Janet Connor of Aspen, Colorado include Hopi dolls, Acoma pottery, Apache baskets, and Navajo and Pueblo jewelry.

The second day of the sale features The Robert S. Miller Collection. One of the specialties at Pook & Pook is 16th to 18th c. brass candlesticks, and the offering from the Miller Collection continues this strength. Over thirty auction lots feature Tudor, English trumpet, Flemish Gothic, Nuremberg, Heemskerk, Spanish capstan, Queen Anne and other candlesticks. Brass wares include a standish, and upright snuffer stand, and a Richard Lee, Jr. strainer, as well as a collection of fourteen fine brass tinder lighters.

American glass has evolved into another strong category for Pook & Pook. The Miller Collection offers many early 19thc. blown three-mold examples including an extremely rare miniature cobalt glass creamer. The collection of glass hat whimsies is the center of much attention. Ranging from the rare to the extremely rare, they include an olive-green bottle glass hat with George McKearin provenance, a purple-cobalt which is one of only three recorded examples, a deep cobalt hat, and a unique amethyst hat, amongst others.

Mr Miller collected early American silver with a focus on his specialty, the silversmiths of Newburyport. There are many chargers and plates produced by many generations of the Moulton family. Newburyport silversmiths Jonathan Stickney, Thomas Foster, and Theophilis Bradbury are also represented. The English silversmith Eley & Fearn was another interest of Miller, including a flatware service ca. 1800-1801 and many individual pieces.

A large collection of America pewter features many plates, chargers, and basins produced by the Nathaniel Austin family, as well as a Charlestown, Massachusetts land sale document from Nathaniel to William Austin, dated 1806.

Mr Miller possessed a lifelong passion for English delftware. Collecting around the world and across six decades, he amassed an extraordinary trove. Pook & Pook has carefully organized rare and precious white-glazed salts, including an important “Curles” master salt, equally rare plates depicting the Crucifixion and the Ascension, sack bottles, fuddling cups, puzzle jugs, pill slabs, and covered jars into over one hundred auction lots of delftware. Chargers include royal portraits, Adam and Eve, pomegranate, tulip, and a cat with mouse. Plates include Merry Man, ballooning, and bianco sopra bianco examples that range from Bristol to London, Scotland, and Dublin.

Rounding out the Miller Collection are many Ithaca, New York stoneware crocks, and German bellarmine and English Fulham jugs, Chinese export porcelains, and a Massachusetts Chippendale cherry tall case clock signed Saml. Mulliken Newburyport, 1780.

For more information please email info@pookandpook.com or call (610) 269-4040. To order a catalog for this auction, please visit www.pookandpook.com.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Still Life

Another of my favorite paintings in the April 18th & 19th sale is also by a Philadelphia native and student of The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Mildred Bunting Miller (1892-1964).

Born in Philadelphia, Miller studied at the Academy from 1910 through 1915 under Thomas Anshutz, Hugh Breckenridge, Daniel Garber, Robert Vonnoh, and Violet Oakley. A recognized talent, she twice won both the Cresson Travel Scholarship and the Mary Smith prize. Mildred’s vocation was set. She wrote “No one knows better than an art student the difficulty- almost the impossibility- of capturing the fleeting beauty that is life. But the desire to do this becomes almost a religion.” (Brown, p.27)

Mildred Bunting Miller has a special connection to our area. After graduating from PAFA at the age of twenty-three, she married classmate Roy Miller, who was hired to manage PAFA’s new country school program in Historic Yellow Springs. Mildred became resident artist, co-director, and instructor. During the years 1916 to 1934, Miller painted and taught classes in the old ochre-washed Small Barn Studio and the surrounding village, which had been purchased in its entirety by PAFA. The country school became wildly successful and extended to year-round attendance. Students were frequently seen gathered around models both animal and human, or found plein air painting among the mineral springs and farm fields. While Miller’s art flourished and was exhibited in museums and galleries, her marriage to Roy crumbled and his management became erratic. In 1934 the Millers were forced to leave the country school, setting up one of their own nearby; but this school was Roy’s dream, not Mildred’s, and although all of her and their money was sunk into it, Mildred departed to paint commissions and teach elsewhere, from New Jersey to Baltimore. Finally, in 1945, she got on a bus for San Diego alone. In California she settled down, buying a small fruit tree farm and teaching art for state-sponsored programs. She relished her independence and lifestyle. Solitude led to more time for painting and for introspection. She filled many journals, which have been published in book form by her niece Virginia Brown, Mildred Miller Remembered. Her writings reveal that her mind constantly returned to the inequity of the male-dominated art world (and world in general) and her years in Chester Springs. Plagued by self-doubt, Mildred’s moods alternated between the elation of a job well done, and the day-to-day reality of toiling in obscurity and achieving little fame or glory. Regardless of the prizes she had won and the praise her work received, she was not considered to be a great artist during her lifetime. She wrote “But when my body is no longer on earth my paintings will still be hung in people’s homes. They will glance at them as they go about their work. They will not think of me! But there I shall be, what I saw they will still have in their minds,” (Brown, p. 181).

Miller’s strong prismatic colors and broken brushstroke technique identify her as a Pennsylvania Impressionist, specifically, as a student of Daniel Garber. Her paintings have clarity, and a masterful handling of light.

In this still life, the table spreads horizontally from the viewer like landscape, the horizon disappearing over the table’s edge like the curvature of the earth, the distant wall the atmosphere. The plane is tilted toward the viewer, the perspective looks down on the dinner napkin, yet there is almost a side view of the wine bottle in the distance. The composition is strong and balanced, with parallel lines and angles that lead the eye. The forms are defined by variation of color. The napkin is sculptural. Miller’s brushstrokes also show dimension, particularly of the table. One of my favorite things about this still life is the tablecloth, with its vertical and horizontal brushstrokes, the latter shimmering like the flakes in an opal. The surface is fascinating, as is the sense of space.

Mildred Bunting Miller exhibited at the Academy, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Corcoran Gallery, the National Academy of Design, the Phillips Memorial, and many other places. Her works can be found in the collection of the Woodmere Art Museum and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

By Cynthia Beech Lawrence

–The Woodmere Art Museum

–Brown, Virginia, Mildred Miller Remembered, Xlibris, 2006.

Marshland

Walter Steumpfig (1914-1970) was one of Philadelphia’s most influential painters of the mid-20th century. A Philadelphia native born in Germantown, Steumpfig studied at The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts under Henry McCarter, Daniel Garber, and Francis Speight. In 1934 he won the Cresson Travel Scholarship for study abroad and headed to Europe, where he studied his idols Poussin, Caravaggio, and Corot. He exhibited regularly at the Durlacher Brothers Gallery in New York, and the Pennsylvania Academy, later becoming the Academy’s teacher of composition and drawing.

Steumpfig’s style was personal and fresh, outside the mainstream of his contemporaries. He considered himself a “romantic realist”, and was noted for his figure compositions and Philadelphia and New Jersey shore landscapes. These views, with just a few people embedded in the landscape, invoke an aura of mystery and detachment in their composition, as in the work of contemporary Edward Hopper, with whom he was frequently compared.

“Marshland” is an example of Steumpfig’s best landscape works. The composition is based on light values and structure. Bathed in the golden light of afternoon, seven boys are engaged not too seriously in activity along the riverbank, reminiscent of Poussin’s shepherds. The intensely illuminated foreground, bare torsos and bright articles of clothing, immediately engage the viewer. The immensity of the river is matched above by a sky with white clouds. On the far riverbank, the afternoon sun illuminates the spring green of the trees, and the undersides of the clouds. The poetic realism sets a mood, sending the viewer back in time to antiquity, but appears fresh, with fluid, modern brushstrokes. It is impossible not to want to join the group on the riverbank and soak in the sun’s rays.

“Marshland” bears a Maynard Walker Gallery label verso. A New York City art dealer from 1935 to 1975, Maynard Walker was among the first to show works of leading American regionalist painters. Walker is noted for organizing the 1933 exhibit in Kansas City that first brought together the works of Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood.

Today Walter Steumpfig’s works can be found in the collections of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Phillips Collection.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

100 Years: The Kindig Legacy

On February 8th and 9th, 2024, Pook & Pook is honored to present the 100 Years: The Kindig Legacy. For a century, the Kindig family of York, Pennsylvania has dealt in the finest antiques available. Joseph Kindig, Jr. opened his first shop in 1925, coinciding with the antique craze that swept America in the 1920s. Kindig’s shop flourished, and put him on the forefront of the expansion of scholarship and collecting. His clients included the foremost collectors of American decorative arts of their time: Henry Francis du Pont, Ima Hogg, Wallace Nutting, and Frances P. Garvan. Kindig shared a close working relationship with du Pont, and the historic Winterthur Collection reflects his expertise. Over his career, he guided Colonial Williamsburg, Winterthur, Bayou Bend, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and many others in the acquisition of masterpieces. In 1947 Joe Kindig III joined his father’s business, and they worked together for twenty years. Joe Kindig III was an intellectual drawn to subjects ranging from architectural history to a continuation of his father’s study of the Kentucky long rifle. He became an authority, researching and uncovering masterpieces. Joe III also curated exhibits for Historical Society of York County, and the furnishing of Wright’s Ferry Mansion, which Kindig termed “the best representation of a Queen Anne house in Pennsylvania.” Joe Kindig III worked closely with Dr. Donald Shelley, whose Pioneer Collection was auctioned for a record $9.8 million by Pook & Pook in 2007. In 1994, Joe III was joined by his own daughter, Jennifer, and the family business flourished into the 21st century. The Kindig Collection reflects the family’s interests and expertise. The furniture is mostly early American, and the decorative arts contain a large percentage of English and some Continental items.

The heart of the Collection’s furniture is regional, with an emphasis on Philadelphia. The earliest furniture includes two pairs of Cromwellian chairs. Pennsylvania William and Mary pieces include several Southeastern Pennsylvania William and Mary walnut wainscot armchairs, a Pennsylvania William and Mary walnut desk and bookcase, and other Pennsylvania William and Mary items including a burl mahogany slant lid desk, stools, chairs, and a tall case clock. Queen Anne highlights include a rare Chester County Queen Anne walnut Octorara chest with removable feet, ca. 1765, and a beautiful Pennsylvania Queen Anne tiger maple dressing table, amongst additional Pennsylvania Queen Anne dressing tables, compass seat chairs, and a tall case clock.

Important Philadelphia Chippendale furniture includes a mahogany three-part desk and bookcase, with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez. A rare pair of Philadelphia Chippendale mahogany gaming tables, also with carving by Jugiez are one of a very few surviving pairs of these tables. A rare Philadelphia Chippendale mahogany piecrust tea table is possibly by Nicholas Bernard. Other fine Philadelphia Chippendale items include a carved high chest, a cherry chest on chest, a dressing table attributed to the “cornucopia carver”, a pair of dining chairs, tall case clock, and two desk and bookcases. Leaving the city limits, Pennsylvania items not to miss include a rare Chester County walnut Octorara tall chest, and a Queen Anne tiger maple dressing table.

Other Chippendale furniture includes a New York mahogany easy chair, and a mahogany games table, possibly from the workshop of Gilbert Ash of New York. A Baltimore Chippendale mahogany high chest was formerly exhibited at the Baltimore Museum of Art on long-term loan. An international highlight is an excellent Irish Chippendale mahogany sofa, ca. 1765.

Notable Federal furniture furniture includes a Salem, Massachusetts inlaid breakfront bookcase, ca. 1800, a Massachusetts mahogany sofa, ca. 1790 and attributed to Samuel McIntire, and a rare Baltimore slab table with King of Prussia marble top.

There is a large art collection with many English landscapes, portraits, equestrian, and hunting scenes. An oil on panel full-length portrait of a young noble girl from the early Stuart period, dated 1619, bears lace so vivid and textural it appears embroidered onto the painting’s surface. A massive Queen Anne burl veneer looking glass, and smaller Queen Anne mirrors, Chippendale looking glasses, and a Constitution mirror, are all perfect for reflecting the candle light provided by a fine collection of early brass candlesticks. The highlight of the early brass group is a magnificent Northwest European Three Kings candlestick, 15th c., one of the tallest and best examples of this form, with Lieutenant Colonel and Mrs. Miodrag R. Blagojevich provenance. English 16th c. Tudor candlesticks, German, Nuremberg, and Northwest European examples complete the group. A large assortment of andirons range from late 17th c. English to 18th c. Philadelphia Chippendale.

Textiles include a large Flemish verdure tapestry, fit for a castle. Complete sets of 18th c. crewelwork curtains, and many finely embroidered spreads dazzle the eye. An extraordinary Continental feltwork spread exhibits a coat of arms and a multitude of figured panels, dated 1749. There are ten English 17th c. stumpwork, beadwork, and needlework framed textiles, including Charles II examples, which depict kings and queens, lords and ladies, and an abundance of flora and fauna. 18th c. English needlework include a silk and metallic portrait of King George, and a pair of George III scenes of the conquest of Mysore which portray the plight of Tippoo Saib hostages. 18th and 19th c. needlework portrays everything from kings and biblical scenes to stately homes.

Silver by early American silversmiths such as Tobias Stoutenburgh, New York, 1721, and Johannis Nys, Philadelphia, ca. 1695, includes a very rare sucket fork by John Brevoort, New York, ca. 1742.

The assortment of delftware includes English Bristol and Lambeth and Dutch examples. A Bristol posset pot and cover stands out amongst the many chargers. An array of Southeastern Pennsylvania sgraffito decorated earthenware includes large dishes and a rare openwork tobacco box and cover attributed to the workshop of David Haring.

Early Pennsylvania German folk art includes valentines, fraktur, and fraktur bookplates, by artists Andreas Kessler, Martin Brechall, the Garden Border Artist, Johann Peter Gilbert, Stephan Meyer, Christian Mertel, Christian Allsdorf, Jacob Oberholtzer, Daniel Otto, and Johann Adam Eyer.

A library of canonical architectural design books contains many first editions, including the first translation of Andrea Palladio published in English, works by Colen Campbell, James Gibbs, Inigo Jones, Isaac Ware, Matthias Darly, William Pain, and the rare The Works in Architecture, London, of Robert and James Adam, Esquires. Furniture design classics include The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker Director by Thomas Chippendale, and The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book by Thomas Sheraton. Ornamental design classics range from Placido Columbiani and Gaetano Brunetti to Matthias Lock and Robert Manwaring. Military subjects include a 1553 Vegetius De Re Militari Libri Quatour, and the 1626 Il Torneo by Bonaventura Pistofilo with engravings of weapons and drills. The Kindig Ephrata books were the subject of an exhibition at Ephrata Cloister in 2012 and feature a very rare 1763 imprint Metallen amongst the mostly religious texts, which include a provenanced Martys Mirror, 1748, and the beautifully illuminated manuscript hymnals for which Ephrata is famous.

Please join us on February 8th and 9th for what is certain to be a major auction event, honoring the Kindig Legacy and its century of scholarship, stewardship, and masterpieces. For more information, please call Pook & Pook at (610)269-4040, or visit our website at www.pookandpook.com.

January 18th & 19th, 2024 Americana & International Auction at Pook & Pook

January 18th & 19th, 2024 Americana & International Auction at Pook & Pook

On January 18th and 19th, 2024, Pook & Pook will hold an Americana & International auction featuring several fine collections. With many rare and exceptional items, there will be much to choose from for trophy hunters. There are thirty-four lots of early American glass from New York and New Jersey containing important and rare examples with provenance. From a New Jersey Collection comes a lily pad sugar bowl on pedestal, ca. 1840 Redfield Glass Works, Clinton County, New York-attributed, of which only a few are known to exist. The same can be said for a mid-19th c. Lancaster Glass Works, New York-attributed lily pad salt cellar, one of the rarest salt cellars known, and an exceedingly rare ca. 1840 New York Lily pad glass compote, possibly Redford Glass Works. From another New Jersey Collection comes an exceptionally rare New York State olive yellow lily pad sugar bowl and cover, ca. 1840, possibly Redwood or Lockport Glassworks. It is described in its accompanying 1946 McKearin receipt as “one of the rarest sugar bowls known.”

From a Pennsylvania collector comes a parade of carved carousel animals from the G.A. Dentzel Company, Philadelphia, ca. 1900-1905, with a rare giraffe leading the way, followed by a running stag, a horse, and an exceptional goat, all with excellent painted surfaces.

The Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Bruno Widmer of Zurich, Switzerland consists of over twenty Amish quilts assembled over the course of decades from communities in Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Ohio.

An Ohio Collection features a wide variety of Americana including gameboards, painted furniture, and folk art.

From one of two St. Louis collections are four excellent 15th/16th century brass candlesticks and an extremely fine Pennsylvania paper cutout, one of the most ambitious cutouts extant. Also from this collection is and what may well be the top lot in furniture, a rare Pennsylvania painted poplar open pewter cupboard, ca. 1760, with scalloped sides.

A very rare Lancaster County Chippendale walnut schrank, late 18th c., features a possibly unique double broken arch pediment and an interesting history with Carnegie Museum provenance. Another fine schrank offered is a Chester County tiger maple example, ca. 1780. A Pennsylvania Queen Anne walnut high chest, ca. 1765, was, according to family history, once owned by Pennsylvania Governor and Civil War General John Hartranft (1830-1889). Another historic Pennsylvania lot is the Jacob Hoestedler family, of Lancaster County, painted pine corner cupboard, ca. 1830. Probably made in Harleysville, Lower Salford Township, Montgomery County, it retains an original bold red and salmon grained surface. A vibrantly painted Berks County tall case clock, ca. 1810, hails from the Machmer Collection. A variety of Philadelphia, New England, and Georgian chairs are represented. A New York Chippendale mahogany easy chair, ca. 1770, is of special note. Among the exceptional offerings from New England is a rare Massachusetts Pilgrim century joined oak chest, ca. 1665-1690, probably Newbury, with provenance. Other New England furniture includes a Queen Anne tiger maple high chest, ca. 1765, a Boston Chippendale mahogany slant front desk, a Rhode Island corner chair, and a Massachusetts Queen Anne mahogany easy chair, both ca. 1765.

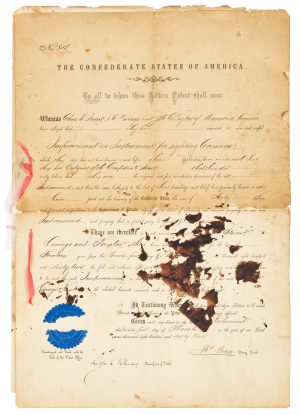

Another item with intriguing history is a rare Confederate States of America Civil War brass cannon patent model, complete with original Confederate States patent papers no. 84, dated 21st day of March, 1862. Most patent models and records were burned as the Confederates abandoned Richmond in 1865.

Artworks featured are a pair of portraits by Jacob Eichholtz (1776-1842) portraying Charles and Frances Blair Pierce of Germantown, Philadelphia. A Massachusetts oil on canvas folk portrait, attributed to Joseph Goodhue Chandler, depicts a lively scene with three children from the Slater family of Webster and their pets. Two other works from Massachusetts are colorful scenes by Elizabeth Mumford. A winter street scene by Hobson Pittman and a Walter Emerson Baum oil on canvas “Grey Day Winter” capture the current weather, while another Baum landscape depicts a fine temperate day. A fine portrait by Sir John Hoppner (1758-1810) is possibly of Henry Wilson. The highlight of the art collection will be a small John Constable oil on panel of a timber and thatch mill above a race, with provenance from the Lady Lever Gallery.

Last but not least, the highlights that sparkle the most brightly are a spectacular La Belle Epoque Ceylon sapphire and diamond necklace and earrings.

For more information about the upcoming auction, visit www.pookandpook.com. For questions about specific items, please email conditions@pookandpook.com. To consign to an upcoming auction at Pook & Pook, please send photographs to info@pookandpook.com or call (610) 269-4040 to speak with an appraiser.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Remedy for a Loose Cannon

The American Civil War is considered the first modern war, witnessing rapid advancement in military technique and technology. Lacking the North’s depth of military resources, it was crucial for the Confederacy to innovate. At inception in 1861 the Confederacy established its own patent office to facilitate and reward innovation. Rufus Rhodes, a New Orleans attorney who had worked with the U.S. Patent Office, was appointed Commissioner. Rhodes would be the only serving Commissioner.

Research by H. Jackson Knight in Confederate Invention: The Story of the Confederate States Patent Office & It’s Inventors, LSU Press, 2011, reveals that during the first year of operation the Patent Office received 304 applications and issued 57 grants. Over its four-year existence, the Office awarded 274 patents, one-third of which were related to firearms and weaponry. Amongst the patents Rufus Rhodes granted were ones for iron-clad armored boats, submarines, torpedoes, and repeating guns.

Patent 84 was issued to Chas. E. Stuart, I.C. Owings, and Jos. H.C. Taylor of Alexandria, Virginia for “Improvements in Instruments for sighting cannon”, along with a receipt for $40, on the 21st day of March, 1862.

Attainment of a patent did not appear to result in payment, as The Journal of the House of Representatives reveals two years later, on May 5, 1864, “Mr Funsten presented the petition of Charles E. Stuart and other patentees for compensation for an invention now in use in the Ordinance Department of the Confederate States; which, on motion, was referred to a special committee of three, to be appointed by the Chair.”

The issue was placed on the Calendar, delayed, and then finally taken up the following year on March 14, 1865. The innovators seemed to be on the cusp of payment. Then, on April 9, 1865, came the surrender of General Lee. As they withdrew from Richmond, the Confederates burned government buildings and records, including the Patent Office. Everything within the Office was lost.

It is exceptionally rare to have an original patent model certificate. It is the only Confederate States patent model paperwork known to exist. It will be sold together with a late 19th c. detailed model of a brass cannon and caisson which exhibits several L.W. Broadwell patents, overall length 28”. Please join us at Pook & Pook on January 18th and 19th to view this piece of history, along with the many other wonderful antiques in the sale.

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

lot 221

A-weema-weh, a-weema-weh

I have had the opportunity to sell things more than once on a regular basis. Sometimes I get things back to be sold in a short amount of time, while some others take a much longer, winding route to come back around. There are many different reasons that I sell the same object. The buyer sometimes has remorse. Sometimes the buyer’s significant other has remorse that their partner ever bought it. I have first hand knowledge of the latter example! One time in the case of a large Belsnickel Santa I bought, my granddaughter hated it and it had to go! There are also those that come back because they didn’t fit in that empty spot, it was the wrong color, or they even bid on the wrong lot. There have also been the perfect gifts, that well, didn’t turn out to be so perfect after all.

I am always amazed in looking at collections the total recall that the collector has. They can tell you exactly what sale, when, where and even the other lots that they didn’t win. Along with those items that they really wanted but could only underbid, it comes with a shake of the head and a muttering of the name of who bought it away from them. These recollections seem to last a life time. The number of times the collector gets that second chance of something that they really wanted is a fairly small percentage. Typically, it doesn’t get away the second time around, no matter what the cost!

I recently had one of those déjà vu moments. While it wasn’t something I wanted or even bid on, it was something that I liked and just stuck out to me. A recent phone call from a long-time buyer in northern New Jersey, whom I have never met, followed by some photographs, sent me on a trip to see a handful of items that they wanted to thin out. As I walked through the house, I selected a half dozen pieces of art, some clocks, a really nice carousel horse and figure, as well a fortune telling bird cage. As we went through the house and into a bedroom there was a very familiar painting. Not a painting with astronomical value, just a painting that stuck out to me. This painting was familiar. As I searched my memory, I started to quiz the client of where the painting came from. He bought it at auction, and it was from a sale in York, Pennsylvania. The light bulb went off. I remember this painting. Before he could speak another word, I filled in the blanks for him. This painting was sold at the Springettsbury Fire Hall on East Market Street in York, Pennsylvania by Gilbert and Gilbert Auctions. His eyes lit up, that yes that is exactly where he bought the painting. Neither of us could remember the year but narrowed it down between 1990 and 1995. So, lot #383, The Newbold Hough Trotter portrait of the lion has come back to visit my life some thirty years later.

By: Jamie Shearer

The Levine Redware Collection

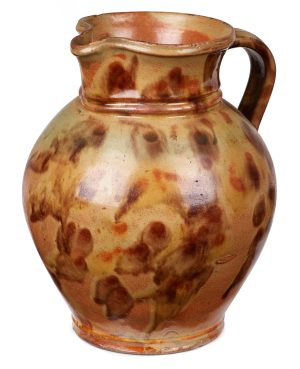

Pook & Pook is pleased to offer in the October 5th and 6th Americana sale a private collection holding some of the most beautiful examples of American redware. Ellen and Richard Levine, of New York, were discerning collectors, finding rare, quality pieces.

Lot 4

Many of the New England pieces are washed in glazes that bring to mind the effects of dappled sunlight on the pebble bed of a clear stream. The colors are of the earth: lead reds, iron ochres, ambers, and oranges, copper greens, and manganese and iron dark purple browns. The greens range from teal to olive, from apple to jade, to a translucent glaze so pale it resembles celadon. Single fields of glaze contain a multitude of colors, mottled, dappled, and dripped together. The variations are the result of the metal oxides in the clay and glazes, drips from other pots, variations in firing temperature, and even the flow of oxygen through the kiln. On some examples, potters fingerpainted or brushed a second glaze of another color, producing blotches and spatters that bloom across the surface, each with an aureole of underlying color. The beauty imparted by each potter is astonishing. The ovoid shapes are perfect in their simplicity. These were utilitarian objects, their production limited to local resources and minerals, with no objective other than to be used for prosaic tasks. Yet each has a graceful, hand-formed curvature, a beauty of proportion, and a depth of glaze that raises them into the realm of art. When viewed together, the group is harmonious, with gently curving lines, graceful proportions, and subtle colors.

Lot 1

Two visually arresting chargers include a rare Pennsylvania or Maryland example with a cream and brown slip decoration of two crossed vines of striped leaves with berries, on a background buzzing with striped ovals. The second is a Pennsylvania charger with yellow and green slip geometric decoration resembling crossed boughs. The transparent green glaze overlaps the yellow, the shadow on the field producing a pronounced three-dimensional effect.

In addition to works by Pennsylvania potters John Bell and Jacob Medinger, a scarce New York redware bottle has a known maker. Attributed to the early Mormon leader Heber Kimball, an amber bottle has blurred concentric bands of green and brown, and a glassy lead glaze. In the 1820’s Kimball worked as a potter in Mendon, purchasing the works from his brother. Soon after creating this bottle, ca. 1830, Kimball was baptized and headed west, eventually becoming one of the first pioneers to settle in Salt Lake City. Another of his bottles is exhibited there in the Museum of Church History.

Lot 5

By Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Press Release: Americana & International Auction, October 2023

Featuring consignments from five noted collectors and several institutions, the October 5th and 6th Americana and International sale at Pook & Pook offers a wide assortment of mochaware, redware, fraktur, and Pennsylvania, Southern, and New England furniture, clocks, and decorative arts, alongside Chinese export porcelain, and international and American works of art.

The first day of the sale begins with a fine selection of redware from The Collection of Ellen & Richard Levine of New York. Among the highlights are two 19th c. chargers. One, a rare Pennsylvania or Maryland example, has an unusual and vibrant cream and brown slip decoration involving two crossed vines and a dazzling array of leaf medallions; the other is Pennsylvania, with striking yellow and green slip decoration that appears almost three-dimensional. A scarce New York redware bottle, ca. 1830, is attributed to the Mormon leader Heber Kimball of Mendon. The collection holds many New England examples in a range of beautiful colors.

The Collection of David and Barbara Mest features Pennsylvania decorative arts and painted furniture. Top lots include a wrought iron straining ladle and flesh fork, dated 1836 and 1835 respectively, with brass and copper inlaid handles; a collection of miniature redware; and a New York or New Jersey stoneware jar with double-sided incised cobalt bird decoration. Another standout is a Pennsylvania painted pine two-part cupboard, early 19th c., with an old red surface and scalloped pie shelf.

The focus of a Mid-Atlantic Educational Institution’s collection is mochaware, including earthworm, cat’s eye, fan, banded, marbleized, and seaweed patterns, appearing on everything from small chamber pots to pepper pots, plates, pitchers, and mugs large and small. Windsor chairs of interest include a Southern long leaf pine and walnut writing armchair, and a rare signed Philadelphia lowback Windsor settee, ca. 1790, branded I. Miller.

The Collection of MaryAnn McIlnay, of York, Pennsylvania, features a fine Baltimore, Maryland Federal mahogany ladies’ cylinder front secretary desk, ca. 1810, with intricate veneer. A Christian Strenge ink and watercolor scherensnitte liebesbrief valentine is designed to capture hearts. A painted pine dower chest, ca. 1790, Berks or Lebanon County, has a vibrant potted tulip panel design. A Northampton County, Pennsylvania Chippendale inlaid walnut tall case clock has a brass dial inscribed John Miller, and extensive tulip and foliate inlay.

Two giltwood girandole mirrors with eagle crests hail from a Pennsylvania educational institution. Among the most colorful items is a herd of caparisoned carousel horses, and a collection of 19th c. turned and painted barber poles. Rare and special items include: a Francis Portzline ink and watercolor fraktur birth certificate, specially made for her own daughter; a Pennsylvania walnut spice cabinet, ca. 1770, with a tombstone panel door and a ten-drawer interior; a Philadelphia Sheraton mahogany pier table, attributed to the workshop of Haines and Henry Connelly; a rare pair of J.W. Fiske cast zinc “Spitz” recumbent dogs; and two Civil War era painted regimental drums. From a Lancaster, Pennsylvania collection are two gemlike Stiegel Glass Works cologne bottles, one in amethyst with diamond daisy pattern, and one pink amethyst in the twelve diamond pattern.

Session I ends with The Collection of Dr. Garrett I. & Bonnie Long, of Romney, West Virginia. Two clocks of note are a Massachusetts Federal mahogany shelf clock, ca. 1810, dial signed Aaron Willard, Washington St., Boston, and a Massachusetts pine dwarf clock, early 19th c., with dial signed Reuben Tower, Hingham. A Southern Federal mahogany Pembroke table, probably Charleston, has bellflower inlays. Diminutive furniture includes a rare miniature Pennsylvania painted drysink, 19th c., and a stepback cupboard, both with original surface decoration, a miniature painted settee, and a New England Chippendale birch child’s slant front desk. An imposing English silver epergne, 1761-1762, bears the touch of Daniel Smith and Robert Sharp. A collection of Chinese export porcelain includes choice Famille Vert, Famille Rose, Rose Medallion, and Canton pieces.

Session II begins with art. A collection from a Delaware Estate includes a John Constable brush and gray wash of fishing boats, a Thomas Gainsborough chalk drawing of a man and horse, a Mary Cassat sketch of a mother and child, two lovely interior mother and child scenes by Jozef Israëls, a harvest landscape in pastels by Léon-Augustin L’hermitte, a School of Peter Paul Rubens chalk drawing of a kneeling woman, and a fine oil on panel portrait of a man, attributed to Hans Bols.

Other marquee artworks include two iconic images of national parks by Gunnar Widforss, a pair of fruit and flower still lifes by Severin Roesen, a riverscape by Edmund Darch Lewis, and a number of Hudson River School works. Other artists include Benjamin West, Robert Street, and Jacob Eichholtz. Nineteenth century animal paintings include two Victorian cats caught admiring themselves in a mirror, an Edward Clarkson portrait of a trotter, two Ben Austrian chick paintings, and a portrait of a terrier by John Emms. Sculptures include works by Andre Harvey, Harry Bertoia, and Frank Finney. The sale features over twenty fraktur and theorem works by David Ellinger.

Session II highlights also include a Pennsylvania Federal mahogany tall case clock, early 19th c., profusely inlaid with a large American eagle on its door. Featured weathervanes are a fancy cast zinc rooster with pleated copper tail, a painted sheet iron Angel Gabriel, a full-bodied copper cow, and a full-bodied copper jockey and running horse. A Carlisle, Pennsylvania silk on linen needlework sampler is wreathed in flowers, and an applique friendship quilt is decorated with a weeping willow and stuffed dove border. Equally ornate, a walnut and tiger maple marquetry inlaid dresser box, 19th c., bears the State Seal of Pennsylvania.

The second session winds down with a collection of property from the Fenimore Art Museum sold to benefit their acquisitions fund. Included in this group is a Pontiac Authorized Service double-sided enameled full feather logo advertising sign, a large oil on canvas Hudson river scene, several portraits, two well executed battle scenes, and Wincester “double W” lithograph ammunition cartridge poster. The sale finishes up with European and Asian material to include silver, furniture, brass, porcelain, clocks, and decorative accessories.

Please join us for this fabulous sale, the week of October 5th and 6th, in-person or online. For more information go to www.pookandpook.com or call (610) 269-4040.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence