The Furniture of Margaret Berwind Schiffer

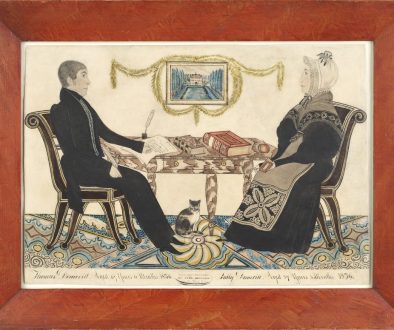

Margaret Berwind Schiffer was a scholar, collector, and an authority on the material culture of early Chester County, Pennsylvania. Researching local records such as wills, inventories, and ledgers, she collected data about early residents, craftsmen, domestic life and home furnishing. Of her first book, “Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County, Pennsylvania”, Charles F. Montgomery of Winterthur Museum wrote that it was “the finest study in depth of the furniture of one county ever prepared.”1 Pouring over countless primary documents, she recognized regional characteristics such as inlay and the production of spice boxes and raised panel furniture, sometimes even revealing the individual craftsmen. Acquiring specimens as she discovered them, over time Margaret Berwind Schiffer built the finest private collection of Chester County furniture known.

Chester County was one of three original counties established by William Penn in 1682. The same year, settlers began arriving from the British Isles, the majority of whom were Quakers escaping religious persecution, along with smaller numbers of immigrants from Germany and France, and non-Quakers. Purchasing tracts of land from Penn they settled into enclaves such as the Welsh Tract in Tredyffrin, the London Company holdings in the southern central region of the county, the Nottingham Lots in the southwestern corner, and Germans in the north. “Most of the early immigrants were middling or poor families from Wales and Cheshire,”2 and many who were not farmers were craftsmen.

According to Schiffer’s perception, “Perhaps the most notable characteristic of Chester County furniture is the decorative effect of a volute inlay.”3 Inlay designs using a series of half-circles scribed with a compass, the ends dotted with a group of three circles, has become known as line and berry. No templates or pattern books have been discovered, and each design appears original.4 The black walnut furniture, usually with oak and chestnut secondary woods (later replaced by oak and poplar), were inlaid with light holly, red cedar or cherry, and black locust. Line and berry production peaked in the 1740’s, and ended in the 1780’s. Line and berry includes other inlay designs such as herringbone borders, compass-scribed stars and flowers, hearts, and dates and initials. It was customary to have a piece of furniture made for a special occasion such as a wedding or anniversary with inlaid initials and dates. In Lee Ann Griffith’s study, of the known 128 line and berry examples, 73 were inlaid with the owner’s initials, and 47 with the date. (The same Chester County Quaker families also purchased initialed Delftware, all dated 1738. Lots #244-247 are part of this very important known group.)

There is now evidence that a number of the earlier examples of line and berry were produced in the Delaware Valley, particularly Philadelphia.5 Christopher Storb’s research has revealed the Delaware Valley/Philadelphia makers used secondary woods of hard pine, red cedar, gum, and Atlantic white cedar, with designs composed of single berries or clusters or four, and more elaborate volutes marked with many compass points.6 Following the migration of craftsmen, line and berry later spread westward and also to the south, down the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road.

Early inlaid William and Mary furniture indicates production began with the first English and Welsh settlers in 1682. While the identity of the first craftsmen to introduce the inlay technique is a mystery, evidence points to the Welsh. In a survey the collection of the National Museum of Wales, Griffith wrote, “While the Welsh designs were much simpler than those that were developed in Pennsylvania, they shared many of the same motifs.”7 Scrolling compass arcs with single berries run across drawer fronts, terminating in tulips, leaves, and diamonds. The Welsh Museum’s inlaid furniture has a history of ownership in southern Wales, in the Vale of Glamorgan, with other known pieces from Pembroke. Griffith finds it is “clear that this vernacular Welsh inlay tradition formed the basis for the school of inlay decoration that developed in Pennsylvania.”8 In “Welsh Furniture 1250-1950,” Richard Bebb attributes the distinctive Welsh inlay specifically to traditional makers of holly and bog oak inlay from the Vale of Glamorgan. (Bog oak, buried in a peat bog for centuries, is nearly black and semi-fossilized.) Other sources the Welsh technique draws upon are English William and Mary boxwood line and arc inlay, and the herringbone checkered banding of the Renaissance. Griffiths concludes the origins of Welsh line and berry inlay are ultimately Flemish. Large Flemish colonies in south Pembrokeshire, first established in the year 1100, influenced Welsh furniture style, making it more closely related to Continental furniture than English.

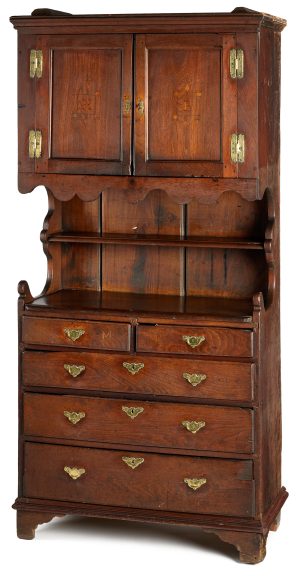

Griffiths found “only one Pennsylvania cupboard bearing any resemblance to a Welsh tridarn (three-part) cupboard”—Lot #24. “Although undated, its Queen Anne bracket feet suggest it was made well after the first Welsh settlement.”9 Of the cabinetmakers working in Chester County before 1720, Schiffer’s data reveals no fewer than twenty with Welsh surnames. The number of Welsh craftsmen is not disproportionately large, meaning the style quickly dispersed throughout the community. The conclusion drawn by Griffiths is that “the popularity of the inlay technique shows consumer demand for locally produced and conceived objects.”10 Of the 128 known line and berry pieces studied by Griffiths, only 31 had original owner or township provenance, with most known owners being of Quakers of English or Irish descent, and only one was signed by the cabinetmaker.

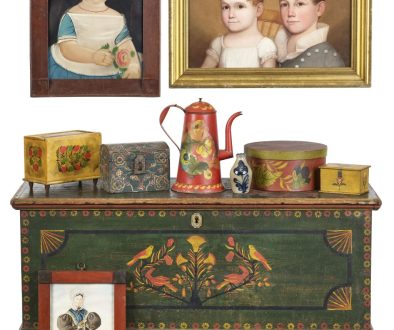

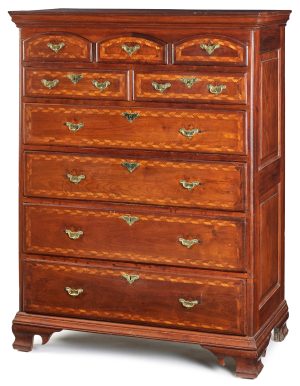

Schiffer writes, “For over two hundred years the population of the county was primarily rural, conservative, and middle class with a strong Quaker element.”11 Conservative Quakers preserved their Old World preferences in rural Chester County long after Philadelphia styles had moved on. “A regional material culture evolved in southern Chester County, manifesting itself in unusual furniture forms and detailing, as well as in the more widespread line and berry decoration.”12 Rooted in English and Welsh origins, Chester County’s Quaker material culture favored the form and construction methods of the late 17th c., with its baroque taste. “The demand for joiner-made furniture which often had raised panels, continued in Wales long after it had died out in England.”13 Likewise in Chester County, even with proximity to Philadelphia and annual trips for the Quaker Yearly Meeting, where craftsmen could see the latest flowing Queen Anne styles in the 1730’s and ornate Chippendale in the 1750’s, favored everywhere else in the colony and Britain, they continued the local tradition of joined furniture throughout the 18th c. Schiffer discerned the localism of line and berry inlay, raised panel tall chests and wainscot chairs, spice boxes, and Octorara furniture, and built her collection.

The ultimate form of Chester County furniture is the spice chest. Inherited from English furniture, “By the early 1700’s, the form had generally ceased being made outside of Pennsylvania, where it continued to flourish among Quaker families in Chester County.”14 These were inlaid with the most elaborate patterns, with pinwheels and compass stars, many with initials that can be traced to their original southern Chester County owners. William and Mary style turned ball feet on spice boxes otherwise in the Queen Anne style is typical of the conservative Chester County makers. Secret drawers are a favorite feature, spice chests actually functioning as diminutive valuables chests. Displayed in the home, they often bore inlaid dates and initials, reflecting their owner’s status. Lot #53, a cedar spice chest ca. 1725, is rare for being decorated on all sides, and is likely an early precursor made in Philadelphia. It opens to a nine-drawer interior, with a hidden tenth drawer. Its “flowerpot with tulips inlay (a motif common in painted Pennsylvania Dutch dower chests) is unusual for line and berry, which did not use objective representation.”15

An inlay motif used in Chester County furniture that has Pennsylvania German craftsmen origins is the parrot. Lisa Minardi’s research suggests that parrot influence may have come from marquetry traditions in Wurttemberg and Hohenlohe, where “bird motifs were so common that the term Papageieinschrank (parrot cupboard) came into use.”16 Parrots were a frequent Pennsylvania German motif because parrots were everywhere at the time. Sadly, that is not still the case, the Carolina parakeet, once native to Pennsylvania, is now extinct. (Lots 28 and 65 parrot) In contrast to the line and berry inlay, marquetry requires large pieces of pattern to be cut whole, with images such as birds or flowers pieced together. “The Continental marquetry style of inlay and the Welsh-derived line and berry style of inlay were practiced within close proximity to one another, influencing one another, but not merging.”17 A perfect illustration of this “interaction between two neighboring cultures” is Lot #14, a tall case clock with works signed B. Chandlee / Nottingham. Benjamin Chandlee, Jr., a Quaker clockmaker, evidently worked with cabinetmakers trained in the German tradition, or his clients bought their cases from German makers. The case is inlaid with marquetry compass pinwheel and tulips.

Herringbone inlay is “rarer than the berry and line inlay.”18 Schiffer’s study revealed it was sometimes combined with line and berry, sometimes with marquetry birds. No pieces bear dates, but the cases appear to be from the first half of the 18th c. Lot #42 has classic Chester County form, with three arched drawers over two, formerly secured with “Quaker” or spring locks, and raised panel sides. A brilliant herringbone pattern borders each drawer. Another technique long out of fashion elsewhere is found on three of the four lower drawers, which formerly hung on side runners. “This continued use of early forms and stylistic details parallels continued use of line and berry inlay in Chester County throughout the 18th c. and was part of the same vernacular tradition.”19 Far from being simply anachronistic, Chester County cabinetmakers were creating their own localized form of the tall chest. Octorara Valley furniture is another distinctive local form, from the western boundary of Chester County. The Queen Anne high chest, Lot #57 with the typical tall, tapering ogee feet with closed circle cut out, and raised panel sides.

Chester County line and berry inlaid, and raised panel furniture are unabashedly beautiful, so how did they satisfy the Quaker doctrine of plainness in material possessions? Given Chester County’s proximity to Philadelphia, the colonial center of culture, furniture making, and a city of very wealthy Quaker families, plainness was a relative matter. Some Quakers were more economically successful than others. Preferring their local styles, which were based on a shared cultural past, the Chester County Quakers chose furniture that was not ostentatious, but still of the very best quality. Chester County vernacular was based on origins, and on identity as a community. Craftsmen used the highest quality materials and anachronistic techniques to create furniture with a perceived honesty and integrity that reflected the values of the conservative, industrious community.

Notes:

1 Margaret Berwind Schiffer, “Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County, Pennsylvania”, 1966, University of Pennsylvania, Introduction.

2 Wendy Cooper and Lisa Mindardi, “Paint, Pattern, and People: Furniture of Southeastern Pennsylvania, 1725-1850”, 2011, University of Pennsylvania, p.8.

3 Schiffer, p.262.

4 Lee Ellen Griffith, “Line and Berry Inlaid Furniture,” 1988, University of Pennsylvania, p. 25.

5 Griffith, p.204.

6 Christopher Storb, “Lines and Dots,” 2021, WordPress.

7 Griffith, p.158.

8 Ibid, p.169.

9 Ibid, p.171.

10 Ibid, p.182.

11 Schiffer, p.10.

12 Griffith, p.156.

13 Ibid, p.170.

14 Cooper and Minardi, p.12.

15 Griffith, p.80.

16 Lisa Minardi, “Philadelphia, Furniture, and the Pennsylvania Germans,” Chipstone, 2013.

17 Griffith, p.194.

18 Schiffer, p.263.

19 Griffith, p.114.