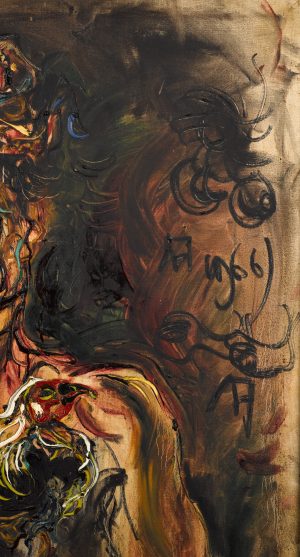

The Father of Indonesian Modern Painting

Kusama Affandi (1907-1990), the father of Indonesian modern painting, was the first Southeast Asian artist to gain worldwide recognition. From his sponsorship of organizations for young artists to the inspiration of his self-taught expressionism, he helped raise future generations of Indonesian artists. Attracting international attention, he traveled the globe, in his earlier years studying in India, participating in the Sao Paolo and Venice Biennales, and in the US on a 1957 State Department scholarship. His career spanned the eras of Dutch colonial rule, Japanese occupation, early independence under Sukarno, and the dictatorship of Suharto. A resident of Java, he was involved in the struggle for Indonesian independence and acquainted with the major political and social actors of his time. His art was influenced early on by participation in artists’ guilds dominated by Lekra, the cultural arm of the Indonesian communist party, and its preference for Social Realism. In 1990 he was honored with a posthumous exhibit at the Smithsonian. Today his work is held mainly in private collections throughout the world, the Singapore Art Museum, the Neka Museum, and the Affandi Museum.

Affandi’s subjects were drawn from ordinary life, especially ones that carried emotional freight, and were painted from reality. His method of painting was all his own, squeezing pigment directly from the tube to create bold lines of impasto, and spreading with his fingers and hands. He believed that blending and swirling, possessed by the moment, would imbue the canvas with his own human spirit and convey more depth of humanity. His spontaneous and dynamic working style captured energy and emotion. Above his signature, he placed his “life symbol” summarizing his style: consisting of the sun, source of energy, life, and creativity; feet for connection to the ground; and hands, powered by his own life force, connecting him to the paint and canvas.

First visiting Bali to paint in 1939, Affandi returned often. The Balinese pastime of cockfighting was a frequent subject of his interest. The Indonesian government opposed the fighting, Islamic tradition being that roosters have the gift of being able to see angels, but allowed its continuation on Bali for religious ceremonies. Blood spilled onto temple grounds is an offering to evil spirits, a sacred purification ritual. Temples in Bali are the meeting place of humans and the gods, where cosmic harmony between humans and the gods above, and demons below, is maintained. Bali-Hinduism is animistic, everything is inhabited by spirits. The unseen spirit world coexists with the human, intertwining in everyday life (Eiseman). The earliest reference to cockerel fighting in the Hindu rituals of Bali is found in the 10th century. After a millennia, cockfighting has taken on a wider social context, to include village friendships, rivalries, notions of masculinity, and gambling. It is deeply rooted as a tradition and pastime. Men raise cockerels like athletes. Training, breeding, diet, and care are endlessly perfected. The cockerels become “symbolic expressions and magnifications of their owner’s self,” and also “of what the Balinese regard as the direct inversion, aesthetically, morally, and metaphysically, of human status: animality,” (Geertz). The blood spilled at cockfights is an offering to pacify the demons of human nature as well. “In the cockfight, man and beast, good and evil, ego and id, the creative power of aroused masculinity and the destructive power of loosened animality fuse in a bloody drama of hatred, cruelty, violence, and death.” The deep religious and social aspects of cockfighting were fertile ground for the artist Affandi.

This canvas, Balinese Cock Fighter, isolates one participant and his treasured cockerel as they wait for their turn to participate, all hopes and fears, in the excitement of the gathering. A shaft of light falls on the pair, the owner’s sinuous muscularity interlacing with curves of the cockerel’s plumage, the bodies appearing as one; as are their spirits, fates intertwined. The negative space in the painting is not empty. Affandi’s swirling fingers and smoky colors evoke the world unseen, the coexisting world of the spirits, the pulsating emotions, and the whirling of natural forces. Ghosts and ancestor gods would have indeed been very present in this unseen world Affandi painted in 1966.

In the summer of 1964, the young nation of Indonesia barely held together as communist, military, and Muslim factions vied for power. In his Independence Day speech, President Sukarno proclaimed the following year would be “the year of living dangerously.” And it was. A failed coup attempt on October 1st of 1965 gave rival Suharto his opening to ascend to power. State-sponsored purges of suspected communists, by both the army and civilian vigilante groups followed. The massacres were brutal, particularly in Java and Bali, with death squads moving from village to village hunting communists. Over the following 18 months, an estimated 500,000 Indonesians were killed and many more were dispossessed or incarcerated. Officially, the period has never been examined. Books about it were banned by the dictatorship. “Its shadow falls across islands where millions live side-by-side with former tormentors or victims.”(The Economist) Indonesians likewise live side by side with the ghosts of the hundreds of thousands slaughtered.

Affandi’s Balinese Cock Fighter, painted in “the year of living dangerously,” provokes a visceral reaction. There is fear, there is the suggestion of pain; it is dark and uncertain. The atmosphere teems with unseen spirits and ancestor gods. Those whirling natural forces that drive the emotions of the cockfight also drive the events of the world. Yet, standing there, their souls bared, they are calm, looking inward. The shaft of light illuminates the key to enduring it all. Amongst the dark clouds and uncertainties, burns the human spirit.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

Sources:

Fred B. Eiseman, National Geographic, 1980.

The Economist, Open Wounds, Banyan, April 23, 1016.

Clifford Geertz, Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight, Daedalus, 2005.

Affandi Museum