Tobias Hirte Redux

Tobias Hirte’s life may have spanned 1748-1833, but he was a man far ahead of his time. In our Photography, Prints, and Ephemera auction on August 18th, Pook & Pook will offer an important and exceedingly rare document demonstrating the contribution of Tobias Hirte to American culture.

Hirte’s parents were wed in a mass ceremony by Count Zinzendorf in the Moravian community Herrnhaag on Zinzendorf’s estate in Saxony. The Moravians heeded the charter of William Penn’s colony and immigrated for religious freedom. In 1771 in the Moravian community of Lititz, Pennsylvania, Tobias Hirte was an assistant schoolmaster and orchestra violinist, living in bachelors’ residence the Brother’s House. Considered either willful and wayward, or ebullient and irrepressible, his antics feature heavily in the community’s records. His life changed in 1777, when General Washington ordered the quartering of 250 sick and wounded soldiers in Lititz after the Battle of Brandywine. The Brother’s House was requisitioned to serve as a hospital, and into the religious community came the influence of the outside world. Tobias Hirte was disciplined in January 1778 for purchasing a flintlock gun for hunting game: “There is no reason why Tobias Hirte should have bought a gun; indeed, on the contrary, it is an unseemliness! What use has a schoolmaster for a gun?” By May, Hirte was in hot water again. To boost morale amongst the convalescents, he organized parties featuring music and merrymaking in an area called the Big Spring. The carousing went late into the night. An exasperated Community asked the head doctor, Dr Allison, “for the love of us, to absent himself from it.” Tobias Hirte was to be “summoned to appear before the brethren of the conference and told not to dare in the future to begin such a thing on our land – for he is given to sudden ideas of such a kind – especially not without permission; and secondly to leave the place of the spring as it now is and do nothing more to it.” During the same eventful time period, another hospital physician, Dr William Brown, was working on his publication “Pharmacopoeia Simpliciorum & Efficaciorum..,” and it is likely that the inquisitive Brother Hirte learned European herbal traditions.

After the Revolution, Hirte set up as an itinerant apothecary, spending half the year in Philadelphia, and half the year traveling, either to his “county seat” orchard in Lebanon, purchased in 1792, or north of the Blue Mountains, visiting his friends the Seneca chiefs Cornplanter and Red Jacket. Although it is unclear exactly when Tobias began exploring the Seneca’s knowledge of medicinal plants, whether as Moravian missionary or apothecary, he now became famous for it. He began bottling and selling a liquid the Seneca skimmed from French Creek as a remedy. Advertised in a 1792 broadside (held by the Library Company of Philadelphia) “Indianisch-French-Crieck-Seneca-Spring-Oel,” was actually petroleum, seeping into the creek from underground. It became a popular medicine. He also advertised the popular “Dr. Van Swieten’s pills”, giving his address “at Mr. Conrad Gerhard’s no. 118 North Second Street the third door above the corner of Race Street – Philadelphia.” Hirte did not just sell snake oil. During the dangerous 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic, he ministered to the afflicted, and the city loved him back. From Ritter:

“Liberty and independence was his motto; and when mounted on his sorrel mare, with saddle bags at each side, and a large umbrella, with a handle of unusual length, on the pommel of his saddle, he bestrode the pinnacle of his glory; and the summer season, from early spring, opened the highway to this enjoyment… Although vending his compounds as he passed the route of his search, his principle object, for many years, was a visit to the Indians – Seneca, and several other tribes – with whom he was on the most sociable of terms and whose chiefs always called on him, at his hermitage in Philadelphia, when they came.”

“Here, in a room about ten by fifteen feet, sat this veteran in nostrums, picturesque in the adornment of his walls with the remains of a music store, fiddles, flutes, French horns, and the like; whilst below, in one corner, stood an old-timed spinet, steadied to the floor by a fifty-six pound weight on its lid or top, in range of which sat the “lord of his survey,” at a table either redolent of roast goose, apple-sauce, &c.; or a mass of pill-stuff, or other medicament, in preparation of a summer’s trip; whilst behind him sat a boy, bottling or boxing curatives for all the ills of human inheritance, spurred to speed by the promise of a feast of coffee and sugar-cake at the end of the week. In front stood a large and very grand – as we thought in those days – mantle clock; but, a little beyond, another, of more importance and more interest. This was a musical clock- a great curiosity; whose Swiss peasantry, in a recess over the dial, took an hourly turn in a cosy dance, to the jungle of a most fascinating set of well-tuned bells, gazed and wondered at by the Schuankfelders, who supplied him regularly on the evenings of Tuesday and Friday, with cream, butter, and Dutch cheese; the latter always most popular for its offensive odor.

He was a bachelor to all intents and purposes, and his apartment a stranger to whisk or water. His habits were unique. He prepared and ate his breakfast of toast and coffee, at about 10 A.M.; lunched on tea and toast, or plain bread and butter and Dutch cheese, at 2 P.M.; but dined sumptuously on roast pig (which he called “spanferkle”) or roast goose, with no small amount of potatoes, apples, cold-slaw, bread and butter, &c., settled with several glasses of good Madeira, at about 11 o’clock at night, and then a pipe; and then, despite homoeopathy, if all within was of doubtful temperament, a goodly number of Von Swieten’s pills – a composition principally of aloes – were sent to check rebellion. Yet he killed the time of near one hundred years.”

It is little wonder that Rudyard Kipling, discovering this wonderful description during an 1889 trip to Philadelphia, would pounce on it for his tales “Brother Square-Toes,” and “A Priest in Spite of Himself.” Kipling’s adaptation is priceless: “We walked into a dirty little room of flutes and fiddles and a fat man fiddling by the window, in a smell of cheese and medicines fit to knock you down. I was knocked down too, for the fat man jumped up and hit me a smack in the face. I fell against an old spinet covered with pill-boxes, and the pills rolled about the floor. The Indian never moved an eyelid.”

Later in life, an 1830 census has Tobias Hirte living as a hermit in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, in his orchard, which was noted for its variety of plants.

Outside of Lititz and Kipling scholarship, Tobias Hirte has largely been forgotten by history. He merits wider acclaim. He was an extraordinary person in an extraordinary place, at an extraordinary time, surrounded by a host of important historical figures. Hirte was a nonconformist, yet influenced by his times. His story contains many elements that shaped early America. Hirte was free-thinking, free-ranging, free enterprising, and, most forgotten, demanded freedom for all, the abolition of slavery.

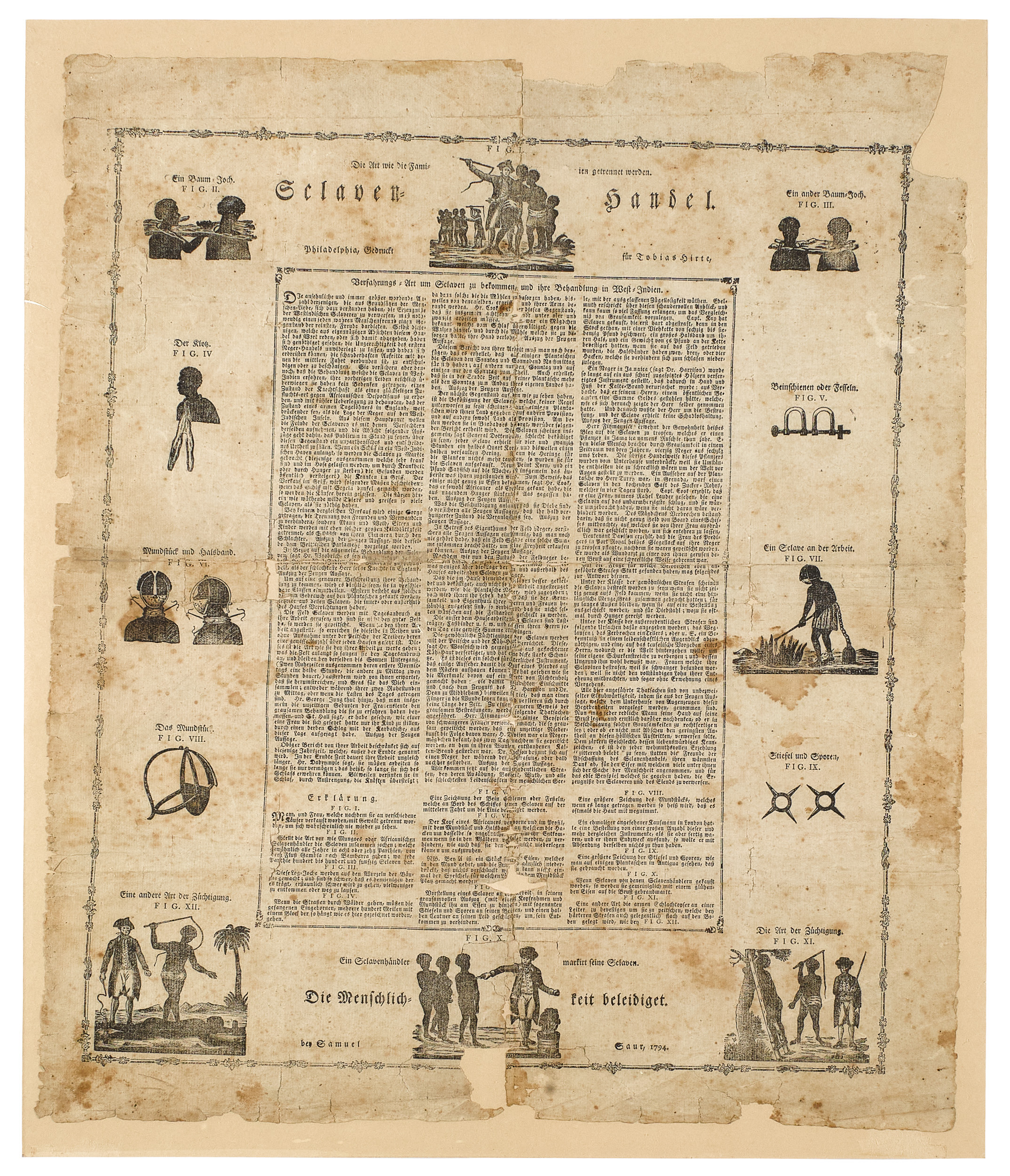

Pook & Pook Inc. is honored to offer one of only three known copies in existence of “Sclaven-Handel. Die Menschlichkeit beleidiget.” (Slave trade. An insult to humanity.) Tobias Hirte’s abolitionist broadside, published in 1794 in Philadelphia. “Sclaven-Handel” is adapted from the 1793 British broadside “Remarks on the Methods of Procuring Slaves,” which was exerpted from the 1791 British report “An Abstract of Evidence Delivered before a Select Committee of the House of Commons,” oral testimony given before Parliament by abolitionists respecting the African slave trade. Tobias Hirte issued his own adaptation in German, ostensibly at his own expense. It was printed by Samuel Saur, of the famous Saur family of printers, in Philadelphia, and illustrated, most likely, by Alexander Anderson (1775-1870) with woodblocks based on the 1793 originals. This was the first appearance of these iconic images in America. Horrifying in nature, the twelve illustrations show the abuses and mistreatment of slaves. The illustrations are one of three sets of 18th century images that were reproduced countless times and were to influence abolitionist propaganda for the next fifty years. They are considered equal in importance to the famous 1789 cross-section of the slave ship Brooks, showing how space was maximized in the hold, and the famous 1787 figure of a slave titled “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” The power of these images cannot be underestimated. They at once convey the apparent victory of evil, and the shame of humanity.

Having fled religious persecution and serfdom, many having endured indentured servitude, German immigrant groups made significant contributions to the anti-slavery movement in America. In 1688, the Quakers of Germantown issued the very first anti-slavery petition in the Colonies. The Moravian church had fanned out across the New World to minister not only to German immigrants and convert Native Americans, but also to bring the support of their God to enslaved Africans. Eccentric as Tobias Hirte’s behavior was, and as much as he exasperated and irritated the Moravians, he was still after all, a Brother. A man of his time, and ahead of his time. Or, as Kipling put it, “A Priest in Spite of Himself.”

by: Cynthia Beech Lawrence

***

Sources:

Lapansky, Emma Jones, “Graphic Discord: Abolitionist and Antiabolitionist Images,” from the Abolitionist Sisterhood, 2018, edited by Jean Fagan Yellin and John C Van Horne.

Martin, Richard, “Toby Hirte: Liberty and Independence,” from the Church Square Journal, Fall 2011.

Lititz Public Library, “Tobias Hirte, Early Lititz Character Repeatedly Aroused Ire of Community,” https://lititzlibrary.org

Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, German illustrated herbal of Tobias Hirte acquisition, May 14, 2020

Ritter, Abraham, History of the Moravian Church in Philadelphia, 1857, pp. 248-250.

Kipling, Rudyard, “Brother Square Toes,” p. 163, and “A Priest In Spite of Himself.”

Beck, Herbert Huebner, “Lititz as an Early Musical Centre,” Lancaster Historical Society, 1915.

Weygandt, Ann M., “A Study of Kipling’s Use of Historical Material in Brother Square-Toes and A Priest In Spite of Himself, University of Delaware, 1954.

Knight, Glenn B., “Tobias Hirte,” The Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society, Vol. 105, No. 3, Fall 2003.

Wolf, Edwin, “Exhibition of Germantown and the Germans,” 1983

Library of Congress, “The Call of Tolerance,” https://www.loc.gov/