A Delft Touch in Colonial America

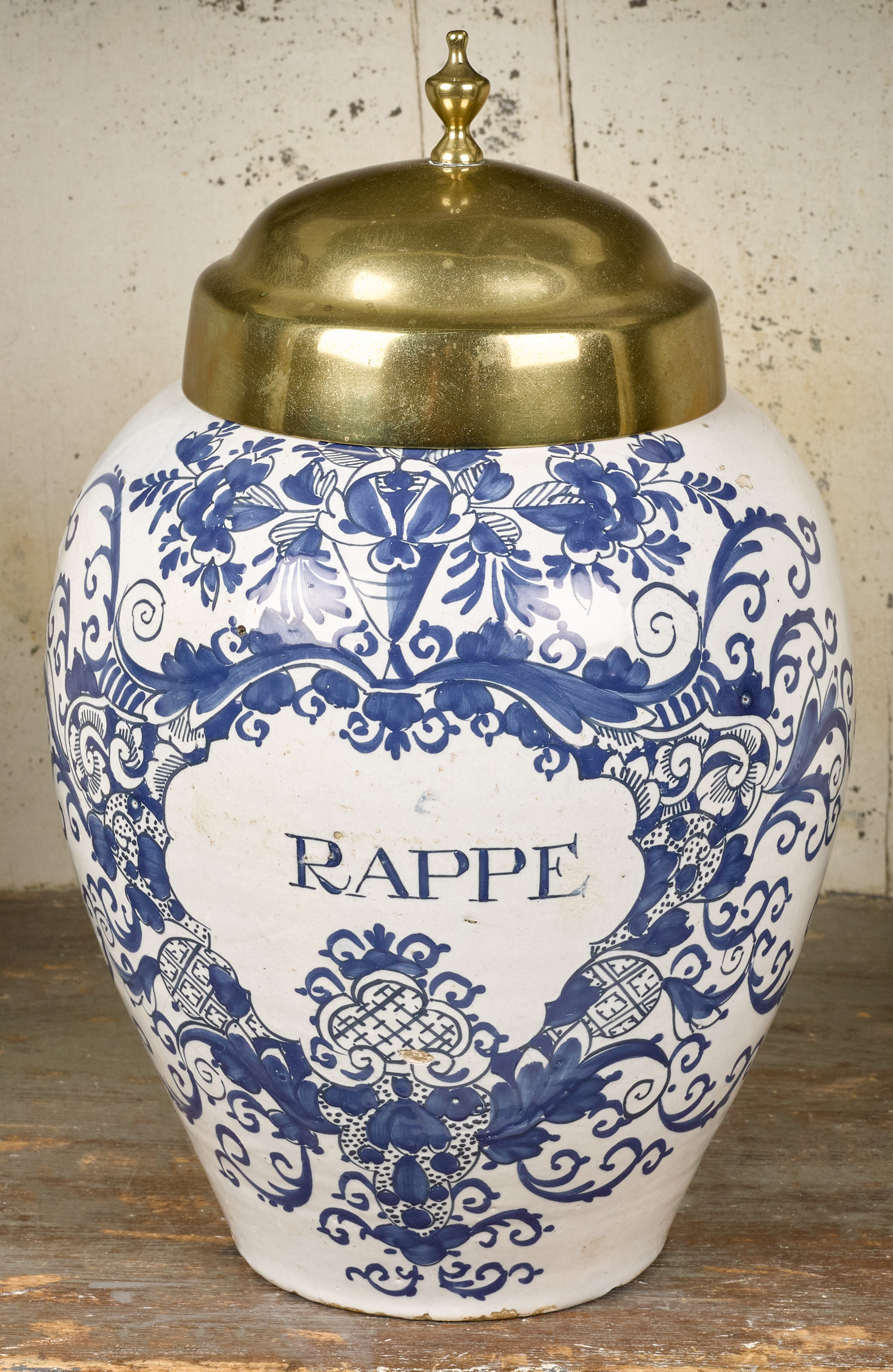

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, Delftware was the most common type of ceramic export to the American colonies, the wide range of products doing everything from adorning elegant tables and displaying flowers to serving utilitarian purposes in apothecary shops and beneath beds (Antiques and the Arts Weekly, Delftware at Historic Deerfield, 1600-1800). By the close of the 17th century, England controlled American colonial trade, but it was the Dutch who dominated global trade, and continued trading in the Americas long after their colonial presence. When England’s 1642 Civil War disrupted supply lines, colonists pivoted to Dutch and French traders. The desire to eliminate Dutch competition gave rise in 1651 to Britain’s Navigation Acts, mercantilist policies designed to protect colonial markets and trade routes. Only British ships were allowed to carry goods to the American colonies, cutting off trade with foreign powers. However, archaeological and archival evidence indicate that Dutch ceramics were common, if contraband. “A minute of the English Privy Council of 1662, concerning the ‘secret trade with the Dutch,’ charges that the plantations were ‘delivering tobacco at sea… carrying the same to New England… and thence shipping it in Dutch bottoms,’ and were committing other illegal practices contrary to the Navigation Acts,” (Charlotte Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade with New England). Colonial governors continued to allow Dutch, Spanish, and Venetian ships to trade in their ports, circumventing British trade policy- particularly with the Dutch. Dutch traders could provide a wide variety of goods needed by the colonists at lower prices. The Dutch were also the largest market for tobacco, colonial America’s most important cash crop. Once in Holland, the imported tobacco was stored in warehouses in Delftware jars designating origin and type, such as rappé for snuff.

By: Cynthia Beech Lawrence